2011 Issue

2011 Writing Awards and Selections for Print and Web

For her essay, “The Yellow Dress,” Patty Carr is the winner of The Metropolitan 2011 Prize for Student Writing, a 13.5-credit-hour tuition remission. The first runner-up, Mark Darby, is awarded 9 credit hours tuition remission for his poem “Thank You, E.B.” The second runner-up, Steven Gale, receives 4.5 credit hours tuition remission for his essay “The Sound of Lavender.”

The Yellow Dress by Patty Carr

Thank You, E.B. and To My Ex-mechanic by Mark Darby

The Sound of Lavender by Steven Gale

October by Brittany Zenor

1984 by Ken McDaniel

Clipped and Threads by Karolinn Fiscaletti

Coffee by Kristin Shaul

Checkmate by Nick Jeanetta

The Carpenter by Vera Lynn Petersen

At Your Two-year-old Pace by Elizabeth Schooler

Web Selections

The Confession of a Mask by Luis Salinas

A Summary and Response to “I heard a Fly buzz” by Tonja West

The “Fat Tax” Issue by Kelly Miskimins

Tone and Style in Sylvia Plath’s “Daddy” by Sara Wilson

Contributor's Notes

Patty Carr is a native Nebraskan and non-traditional student at MCC. Rather than changing her area of study each trimester, she has decided to just take whatever interests her at the time, although she would really like to take creative writing with Brett Mertins over and over again. Patty lives with her husband of 29 years and has 3 grown children. Shortly after completing creative writing, Patty joined the staff of WorshipOutlet.com as a writer. “The Yellow Dress” is dedicated to Mr. Brandt, a former high-school English teacher, who told Patty to steer away from college classes which involved writing.

Mark Darby returned to MCC after being out of school for thirty years, taking several courses before returning to the University of Nebraska Medical Center to begin work on his masters in nursing degree. He is at work on a dramatic novel about the two nurse midwives in Exodus Chapter 1. He is married and has two children.

Steven Gale is a chef with over thirty years in the kitchen. He has had a lifelong love of literature but only recently found that he had some small talent in writing. He plans to continue his studies in that area.

Nick Jeanetta was born in Lincoln, moved to New York City for a year when he was one, then moved back to Omaha where he has since stayed. He has traveled to Belize, Brazil, Italy, and around the continental US. He will graduate with a degree in computer engineering if it kills him (which it probably will).

Ken McDaniel has bachelor’s degrees in finance and history from the University of Oklahoma and a master’s in business administration from the University of South Dakota, Vermillion. He is currently working on his associates degree from MCC. He has written nine novels and published two. The short poem “1984” is about a woman he knew when he was younger and wiser.

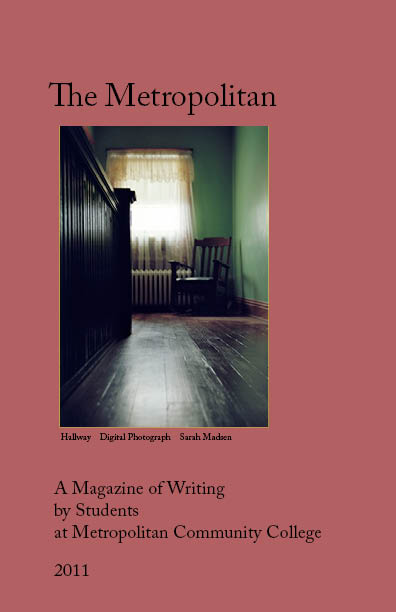

Sarah Madsen is an Iowa native, currently finishing her degree in commercial photography. She hopes to one day own her own photography business.

Kelly Miskimins is originally from Vermillion, South Dakota but has relocated to Omaha for school. She currently attends the baking and pastry program at MCC. Although baking is her passion, she has always dreamed of being a published writer and enjoys writing whenever she gets the chance.

Vera Lynn Petersen (formerly Hough) graduated from Millard North High School in 2006. She has been taking studies at both Metropolitan Community College and Grace University to earn a degree in psychology. In her spare time, she loves to write poems and short stories, along with painting and drawing. With her degree, she wants to help children express themselves through art and writing as a form of art therapy. She was inspired by her husband, who is a carpenter, while writing this poem for creative writing class at MCC. She hopes to continue writing poetry and achieve the goal of writing a novel by the age of thirty.

Luis Salinas is from Saint Louis, Missouri originally and moved to Omaha for an internship. He liked it so much he stayed. Luis is an American Latino of Bolivian background and proud of his heritage and culture.

Kristen Shaul is a licensed practical nurse who is pursuing her associates degree in nursing at MCC. She enjoys writing, traveling, and spending time with her husband and two energetic daughters.

The Yellow Dress

Patty Carr

At no time in the past four decades had Beth seen her

mother—or at least the woman she called mother—so unsettled.

It was a relief, then, when Mother stood up and announced it

was time to start. Beth and Sarah quickly fell in line, and the trio

of Oakley women made their way up the wooden staircase, which

seemed to moan a “welcome home” with each of the sisters’

steps. Thirty years earlier, Beth easily silenced the old house with

strategically placed feet, but today, squeaky stairs would not be

the tattletale of secrets.

“I will miss many things about this old house,” said Mother,

“but not these stairs.” She paused at the first landing to catch

her breath. “I could carry the laundry only this far yesterday,” she

said, bending to pick up the abandoned laundry basket.

“I’ll get that,” said Beth, reaching for the basket and

recalling the precision with which Mother packed a laundry

basket: socks rolled into uniform-sized balls, perfectly folded,

bleached undershirts, stacks of hand towels and guest towels—

separate piles, organized by color, of course, and “Oh my gosh,

Mother, don’t tell me you are still ironing Dad’s boxer shorts!”

“I’m so glad your new house has everything on one floor!”

Sarah said, redirecting the conversation. “Your life is going to be

so much easier there, don’t you think?”

Mother muttered something like “umm huh,” which was

all the sound she could muster after reaching the top step. She

turned right and headed toward her room, stopping at the

hallway bookshelf as if to wait for the others, but really wanting

to catch her breath. Beth and Sarah darted around the upstairs

rooms, delivering clean laundry to the places they had occupied

for thirty years. Mother waited by the bookshelf, which sat like a

wooden coffin, holding lifeless memories that no one wanted, nor

wanted to discard.

By the time Beth and Sarah finished, Mother had moved to

her room and was perched at the foot of her perfectly coiffed bed.

The way she sat—left foot tucked behind the right, back straight,

hands folded in her lap—reminded Beth of the garden bench in

the backyard where a concrete angel sat as guardian of the dead,

keeping vigil over Scout, Trixie, and countless gerbils wrapped

in paper towels and placed in red checkbook boxes for all of

eternity. Beth wondered if it was proper to tell the new owners

there were animals buried in the yard. She made a mental note to

ask the realtor about that.

Beth and Sarah entered the bedroom, careful not to seem

too familiar with a space supposedly off limits but covertly

explored anyway.

“Okay!” said Beth. Beth said “okay” a lot. The word could

mean many things but always meant she was taking charge—

something that never bothered Dad or Sarah, but was always

a source of contention with Mother. Today, however, Mother

seemed relieved to have someone else, even Beth, take control.

The bedroom had been painted seafoam green thirty-four years

ago. A dresser and vanity set, circa 1960, sat against the wall

facing the bed. In the corner of the room, an oak door with a

beveled built-in mirror led to a walk-in closet tucked under the

eaves of the 1905 mission style home. Beth walked around the

bed to the corner of the room and pulled back the seafoam green

drapes, exposing five east-facing windows which overlooked the

front lawn. She had hoped to bring some morning sunlight into

the room, but instead she found the skies had clouded over. Even

so, it was brighter with the drapes pulled back.

“Okay. Shall we start with the closet, vanity, or dresser?”

asked Beth. No one answered. This house had been a shrine to

orderliness for fifty-three years. In fact, Beth often teased that

she was going to replace the old tarnished door plate that read,

“God’s peace to all who enter,” with a shiny new one that read,

“A place for each thing—and each thing in its place, ” which had

become the unspoken but obeyed motto of the house. Mother

had always chided back, saying, “With that on the front door,

you’ll never be able to visit, Liz.” Beth hated to be called “Liz,”

which Mother knew too well.

Beth had complied with her Mother’s wishes to go by

“Elizabeth” until the eighth grade, when she was faced with a

sewing project that required students to make letter-shaped

pillows spelling out their names. “Elizabeth” quickly became

“Beth,” a name more suited to her personality anyway. Mother

responded by saying that if Elizabeth preferred a shorter

variation of her name, “Liz” was shorter than “Beth” and also

sounded “more efficient.” Mother had continued to call her

Elizabeth, but would occasionally call her “Liz” just to prove she

could, in fact, change. Now, Mother faced the greatest change

of her life. In just three short weeks, everything in this house of

order would be torn apart, sorted, auctioned off or packed and

moved to a house one-third the size. Just how should one go

about dismantling a lifetime? How many boxes does that require?

No one knew. And no one could decide where to begin.

“Shall we start with the vanity?” asked Sarah. Ambivalent

nods from Mother and Beth signaled it was as good a place as

any to begin. Sarah pulled out a drawer, set it on the floor, sat

down beside it, and began to explore. Mother began to toy with

her hands, eventually clasping her right hand over her left, as if

to prevent herself from pointing toward the door and shouting

“Out!”

“I think we should make four piles,” said Beth. “A pile to

pack and move. A pile to throw away. A pile to give away. And a

pile for the sale. Sound okay?” She pulled a plastic garbage bag

from her pocket and shook it a few times. Sarah had already

found something interesting.

“Look how dark your hair is, Mother. Do you want to keep

this picture?”

“I hadn’t even started to dye my hair yet. Yes, we have to

save that!”

For two hours Beth and Sarah pulled trinkets, playbills,

handbags, jewelry, scarves, and vacation memorabilia from the

drawers. Mother told a wonderful story about every item: a pearl

brooch she received for being homecoming queen in college, the

fancy beaded evening bag she took to Christmas cocktail parties,

the silk scarves she bought for one dollar each when Levitt’s

went out of business, the last Vera Neuman scarf her mother gave

her before she died, a box of coins from an old maid at church,

a gold charm bracelet with a gold heart inscribed, “I love you,

Frank.”

“I think there’s something you’re not telling us, Mother,”

said Beth with a coy smile, attempting to lighten the mood

against the darkening skies. “Who’s Frank?”

“Oh, Frank. He was in the Navy. He kept sending me

things. I didn’t even like him, but it must have made him feel

good to think he had someone to send things to. I don’t care

what you do with that.”

“Well, finally!” said Beth. “Something for the auction pile.”

Mother looked toward her, lowering her head and looking over

her glasses.

“I know this is hard, Mother, but you do not need these

things. These scarves still have the tags on them. Levitt’s closed

eight years ago. If you haven’t worn them by now, you’re not

going to wear them.” Beth paused. There was no backlash, so she

continued. “And you can have wonderful memories of Grandma

without keeping everything she gave you,” said Beth, picking up

the crocheted butterfly magnets that had remained trapped in a

snack-sized baggie at the bottom of a drawer since 1994.

“I want to know what happened to Frank,” said Sarah,

making another attempt to redirect the conversation.

“I don’t really know. I stopped getting mail from him. He

either died or found someone else to send things to.”

“Okay! Back to business,” said Beth. “Can you pick just a

few of Grandma’s things to save?”

Mother pursed her lips. “I want to keep these things, and

that’s that! They’re special to me. And I give those scarves to the

little widows from church who die without a nice outfit to be

buried in. A new scarf just spruces them up so nice and makes

them look like someone cared about them.”

“Yoo-hoo,” came a familiar voice from the back door.

“Oh good, Dorothy’s here. She’ll be on my side,” said

Mother, as she stood, paused a moment to let her joints adjust,

then headed toward the back staircase at the opposite end of the

hall. Beth and Sarah gave each other a cautious look until they

heard the sound of Mother’s footsteps on the back staircase.

“Do you think she’ll notice if we move some things to the

‘auction’ pile?” asked Sarah, leaning forward to see out the door

and down the hall, making sure Mother was out of hearing range.

“You know she’ll notice. And if I die before she does, do not

let her put one of those scarves on me. Can you believe she even

finds fault with people after they’re dead?” Beth had picked up a

scarf with obnoxiously large purple roses and tied it around her

neck. “What do you think? Would this go well with death?”

“You look well loved,” said Sarah, and they giggled as sisters

do. “I think this will get easier as we go along. It’s just going to

take her a while to get used to the idea.”

Beth looked toward the ceiling, closing her eyes and

drawing in a deep breath. Sarah knew she had said something

wrong, but what? She quickly played the words over again in

her head. Beth exhaled, and it was as if all the happiness blew

out of the room. When she opened her eyes, the mischievous

twinkle from a moment ago had been replaced with the sad,

searching eyes that had never been able to find what they were

looking for—whatever that was. Beth thought for a moment.

“Meanwhile, we’re giving up our entire weekends for the next

month. You’re missing Sam’s championship game, and I’m not

going to make any money this month. I’m already two weeks

behind on orders because of my surgery, and now another four

weeks …. You know, it wouldn’t be so bad if she just appreciated

our help, but she expects it, like we owe her. Why did she even

adopt children? She doesn’t even like kids! Well, she liked you, I

guess, but that’s because you were thin and popular … and could

sing … and were always on Honor Roll and ….”

“Oh, stop it. You know that’s not true. She’s not partial at

all—she dislikes us equally,” said Sarah, bringing a little smile

back to Beth’s face. Beth flopped down on the bed, propping a

pillow underneath her chin. “When are your orders due?” asked

Sarah, making her way from the floor to sit beside her sister on

the bed. “I can help you, maybe, if there’s something that doesn’t

require sewing talent.”

“No. You’re sweet—thank you though. One order is for

eight teddy bears made from a quilt.” Beth rose up on her elbows.

“I can’t believe I’m going to cut up this gorgeous quilt, but the

family couldn’t decide who should have the quilt, so everyone is

getting a little teddy bear instead. They’re in no hurry. The other

order is for my neighbor. It’s just some pillow slipcovers, but I

told her they’d be done by now.” Beth lay down again, turning

her head toward Sarah. “Do you know she didn’t even call me

after my surgery? Dad was there every day, and she didn’t even

call.”

Sarah closed her eyes and shook her head back and forth. “I

wondered if she did, but I was afraid to ask.” Sarah’s eyes welled

up a bit, not out of pity, but because she understood how it felt to

miss the compassion of a mother.

“Well, it’s not like I expected her to be there. Why would

I think she’d start to care now?” Beth and Sarah looked at each

other and understood what only each other could understand.

“I’m okay!” said Beth. “That’s what therapists are for, right?”

“And antidepressants. Don’t forget antidepressants,” said

Sarah.

While Mother and Dorothy visited downstairs, Beth and

Sarah packed up all the things in the “move” pile, letting a few

items find their way into the “sale” pile, which they packed in a

different box and set in a different room. After another hour, all

evidence of life had been removed from the bedroom. Raindrops

fell like tears down the windows of the house. Beth pulled the

drapes closed and shut off the light on her way out of the room.

Sarah made her way up the stairs with an overly ambitious

stack of empty boxes. At the top of the staircase, she gave up her

balancing act and let the boxes come tumbling down around her

feet. Dad was behind her, carrying a smaller stack.

“Gosh, I don’t know what I’d do without you girls,” said

Dad. “The best thing I can do is stay out of the way. How is it

coming along?”

“She’s tough, but we’ll break her,” said Beth, peeking around

the door of a hallway closet where she was filling a garbage bag

with sacks of old Christmas cards labeled with the year in which

they had been received. They could hear Dorothy leaving through

the back door and knew their time of unsupervised packing was

nearing an end.

“That’s my cue,” said Dad.

“Here,” said Beth, handing Dad the garbage bag full of

Christmas cards, “get this to the garbage without her seeing!”

“Dinner’s on me,” said Dad, his bad knees taking him down

the front staircase as fast as they could. “Anyplace you want! I

don’t know what I’d do,” his voice trailed off, but Beth knew the

familiar ending, and it made her smile.

Beth grabbed two empty boxes and threw one to Sarah. “I’ll

pack up the yarn, you pack the fabric scraps. Mark them ‘sale.’

Hurry!” The sisters packed and labeled the boxes before Mother

appeared at the top of the back staircase.

“Well, I told Dorothy I spent your inheritance on a new

house,” Mother said, with a taunting smile that didn’t get the

reaction she’d hoped for. “You didn’t give anything away I wanted,

did you?”

“Of course not,” said Sarah. She went into her old bedroom

and returned with a white straight-backed chair, which she

placed in front of the hallway linen cupboard. Mother sat down

as if it were her throne, and her royal subjects scurried to work.

“You didn’t want to save all those old fabric scraps, right?”

Beth asked.

“I want to give them to my church. They make quilts for

the widowers. Isn’t that nice?” Beth scratched out “sale” and wrote

“church” on the box. Sarah, taller and more agile than Beth,

began unpacking the top shelf of the linen cupboard, pulling out

stacks of towels from the top shelf and handing them to Beth,

who sat on the floor facing Mother.

“Oh my gosh, I remember these from when I was little,“

said Beth. “Why did you keep these?”

“I might need them some day.”

“You’re never going to need towels from 1970, Mother.

Let’s save the new, unused towels and put the old ones in the sale

pile.”

“It won’t hurt to save all of them.”

“You won’t have room for all of them.” Beth rose up on her

knees, reaching for a box.

“I want to save them.”

“You don’t need all of them.” Beth placed the towels in a box

and began to write “sale.”

“If I’m poor someday, I can sell the new ones and use the

old ones. I want to keep them all.”

Beth stopped writing and looked at Sarah, who had also

stopped unloading and was now looking at Mother. The girls had

never heard Mother say such a thing. Is this what the struggle

was really about? Were all these unnecessary items Mother’s

rainy day security? Her emotional portfolio of sorts?

“Mom, you’re not ever going to be poor. You’ve got enough

money to buy towels for everyone in town.” Mother’s hands were

fidgeting as if she were running some quick calculations. She

took a deep breath before saying, “Okay, maybe just these towels.”

Sarah resumed the process of pulling things from the

cupboard: leftover napkins and paper plates from birthday

parties, Christmas presents that had never been given, boxes of

photos collected from dead relatives, silk sachets which had long

lost their scent, sheets that fit beds the family didn’t have.

Sarah had been right. As the day progressed, Mother

became more comfortable with letting go. Beth even began to

enjoy some of the stories. When Sarah pulled out a pair of red

wooden candle holders, Mother’s stoic posture relaxed and a

natural smile came over her face. She held out her hands. Sarah

blew off the dust and handed the candle holders to Mother.

“My Uncle Lars carved these for me. See how they are

painted with Swedish designs.” She slowly ran her fingers over

the raised white paint designs, inspecting each detail before

handing them to Beth, who carefully wrapped them in bubble

wrap and gently placed them in the box labeled “move.”

Next, Sarah pulled out a set of three wooden bowls, nested

inside each other. Mother’s posture stiffened—an obvious

response—and the forced, more familiar smile returned to her

face. “We will save those as well. Those bowls are the only thing

my dad ever gave me. Ever.” Beth waited for a moment before

taking the bowls from Sarah, wondering if Mother would want

to hold them as well, but her hands remained tightly clasped in

her lap.

“Well, that’s enough for today,” said Mother. Beth and

Sarah exchanged concerned glances, knowing that more work

needed to be done if they were going to finish on time.

“Why don’t you go down and watch Wheel of Fortune with

Dad, and we’ll just clean up our mess,” said Sarah.

“I’ll know if you give anything away I want to keep,”

Mother said, making her way down the stairs.

The rain had stopped, and the sun was pressing against

the clouds, desperate to break through. Sarah opened the door

to her old bedroom, letting a small bit of light into the hallway.

They continued to work, not speaking much now, unknowingly

contemplating the same things: Mother’s fear of being poor, her

love of Uncle Lars’ candlesticks, the bowls. Beth pulled a white

box out of the cupboard and eased back to the floor, her incisions

still pulling a bit when she sat or stood. She opened the box and

pulled back the light blue tissue paper, giving a little gasp.

“Sarah, look! Do you remember these?” Sarah sat down

by Beth and watched as Beth tenderly picked up a little yellow

doll dress made of a sheer floral-print fabric. She touched the

baby doll sleeves, studying how evenly they were gathered. She

flipped up the bottom hem to see how the miniature lace had

been attached. “Someone made these by hand,” said Beth. “Oh

my gosh, look at these tiny snaps sewn down the back. This must

have taken forever to make.”

“What about this?” said Sarah, holding up what looked like

a plain yellow sleeveless dress.

“Oh, the petticoat!” said Beth. “I remember.” She laid

the dress on the floor, smoothed it out flat, and then took the

petticoat from Sarah. Holding the petticoat by the top, she

slipped it inside the dress. “See, look how the flowers have more

depth with the petticoat underneath.” She held it up by the

shoulders and moved it around a bit, admiring every detail. Look

at this neckline! I’ve never done a neckline so perfect on adultsized clothes! There was a coat as well,” said Beth. “Is it in there?”

Sarah lifted the next layer of tissue inside the box. “How

‘bout booties?” said Sarah.

“They look hand-knit,” said Beth reaching out to take them

from Sarah, inspecting them carefully before laying them gently

on the floor, a few inches below the dress.

“A coat!” said Sarah, raising it from the box. “Wow, even I’m

impressed.”

“Let me see, let me see!” said Beth, trying to scoot closer to

Sarah, but forgetting about her incisions. “Ouch!” Beth winced

and grabbed her stomach.

“Beth, are you okay?”

“No—no, I’m not. I might die any second,” said Beth,

purposely being dramatic. “All I want is to hold the coat and

remember my childhood one last time.”

“I didn’t know you had a childhood,” said Sarah, tossing the

coat at Beth.

“Don’t throw it! Of course I had a childhood. It lasted five

weeks.” Beth maintained her serious composure until Sarah

rolled her eyes. Then they both smiled. Sarah said something

else, but Beth didn’t catch it. She was lost in the tiny stitches

that had sewn mother-of-pearl buttons to the front of the pale

yellow corduroy doll coat. “Amazing,” she whispered. She rubbed

her index finger back and forth over the velvet trim and felt the

coolness of the satin lining with the back of her hand. “So much

work.”

Mother’s footsteps were on the stairs again, but this time

neither Beth nor Sarah jumped into action.

“I don’t trust you to pack without me,” Mother announced,

giving the girls fair warning of her approach. “I won at Wheel

of Fortune, but Dad is getting better,” she said in her slightly

breathless voice from the landing. Soon, her feet were on the

steps again. “Oh, you found the little doll clothes I made.”

Mother sat down in the chair, not so stoic this time, with the

natural smile emerging for the second time in the same day.

“You made these?” Beth questioned.

“Oh yes. I would stay up after you went to bed and work on

them for hours. It took weeks to complete this set. Did you find

the blue set, too?”

Sarah lifted the tissue and pulled out another complete set

of clothes, a pretty slate blue.

“I don’t remember those,” said Beth.

“For some reason you always chose the yellow set. Your

little dolly was so special to you that I wanted to make her some

very special clothes. I made matching pajamas for you and your

dolly, too. Do you remember those?”

“With kittens! Yes! I had forgotten all about those,” said

Beth, looking eerily calm and confused at the same time.

“Voila!” said Sarah, lifting a small flannel nightgown with

pink kittens chasing balls of gray yarn.

“They’re beautiful, Mom. They’re sewn perfectly.” Beth had

lifted the soft flannel nightgown to her cheek now. “Why would

you spend the time to do such exquisite work for a four-year old

who couldn’t appreciate it?”

“I didn’t care whether you appreciated it or not. I just

wanted to do it for you.”

“Amazing,” Beth said quietly to herself.

“They are well made, aren’t they?” said Mother, picking up

the yellow coat to examine it more closely. “I suppose some little

girl could still use them.”

“Oh no,” said Beth. “I will hold on to them.”

A faint bit of sunlight now streamed into the hallway

through Sarah’s windows. Once again, mother’s silhouette

reminded Beth of the garden angel statue, the guardian of

cherished things long gone.

Thank You, E.B.

Mark Darby

My adventure begins, not with compass, canteen and Khaki jacket, but with the words: “Where’s Papa going with that ax?” Boys play marbles in the dirt and jump ramps with a six-speed Schwinn. They don’t cry at Charlotte’s tiny death, but in sixth grade study hall, near the library encyclopedias, I do.

To My Ex-mechanic

Mark Darby

Like Tarzan, my blue shirted mechanic beats his chest

with a ¾ quarter inch socket wrench

as he demands I hear the whistle from under the hood.

“Me fix, you pay.”

He wants bananas, many bananas,

for his chimp, I imagine.

I feel helpless until I remember

I have wrestled with a 1976 AMC Matador and

I have scrubbed axle grease from my fingernails with Brillo Pads.

I will give him no bananas.

My car whistle echoes as I swing from his jungle garage

The Sound of Lavender

Steven Gale

I was driving down the road to Apt in a rented

Renault. Like most French cars I had ridden in, this one was

underpowered and undersuspended, and I felt every bump and

rut in the road as I struggled up hills and flew down them. It was

a beautiful sunny day, and I understood why blue and gold are

the official colors of Provence, blue for the sky and gold for the

sun. As I topped a rise, I saw what should have been the third

color—purple, or lavender to be more precise. As far as I could

see, from horizon to horizon, laid out in perfect geometric rows,

was lavender in full bloom.

I was stunned by the sight. I took my foot off the

accelerator pedal without knowing it and gradually coasted to a

stop, in the midst of this sea of flowers. I turned off the ignition,

stepped out of the car, and was almost bowled over by a wave of

scent. It was floral, and herbal, and what I remember most is that

this is what clean smells like.

I scanned the road ahead to see if I could see one of the

many roadside stands that dot the countryside in these parts,

for that was what I had come here for. Not the flowers, but

the honey, the famous miel de lavande of Provence. It is sweet,

without being cloying, floral, without being too flowery; in short,

it’s perfect. It’s one of those little wonders that God got right

the first time, and I have no doubt that if there were four Magi

instead of three, the fourth gift would be one of honey. I didn’t

see a stand anywhere near, but I did see a young woman bent

over the lavender beside her car, cutting a bunch that I assumed

she would make into sachets to put amongst her linens, as is the

Provencal custom. Wouldn’t the farmer mind her cutting his

lavender like that? In the midst of such plenty, I supposed that he

would not.

It had been a long ride, and I still didn’t have my honey, so I

decided to stretch my legs and walk for a distance into the field. I

had the sun on my face, Mozart playing in my head, the scent of

lavender in my nostrils, and for one bright shining moment God

was in his Heaven, and all was right with the world. I was so

“blissed out” that it took me awhile to hear it—a low, humming,

thrumming sound that I could feel on my skin, like electricity.

It was like standing next to a large electrical transformer. I

eventually made the connection. Where there is lavender there

is honey, and where there is honey there are bees, and what I was

experiencing was the sound and energy of a billion busy bees,

besotted with nectar.

I remember many things about that day, but after all these

years it’s the sound, the sound of lavender that I remember most.

October

Brittany Zenor

Time leaps past

the trees

in the park,

and the path

is littered

with leaves

that have languished.

Some listlessly drift

to the crunchy

and crowded ground.

Glowing pumpkins

peer from porches

at passersby,

and wailing wind

walks down deserted paths.

Death destroys

bountiful hope

with gunshots

and guillotines.

Fear flies under doors

and fights with fire,

fleeing ferocious death.

Fire fights back,

and the smoke

of victory seeps

through thousands

of chimneys.

1984

Ken McDaniel

These are two stories.

Black is white.

The first looking forward,

of socialism, communism

and doublethink.

The introduction of

a raven-haired mechanic,

an illicit love ending

in confession and betrayal

with a bullet to the brain.

Then another,

white is black,

looking backward,

of capitalism, individualism

and doublethink.

The introduction of

a raven-haired innocent,

a licit love, ending

in confession and betrayal

with a bullet to the heart.

Memories left

under the chestnut tree.

I sold you

and you sold me.

Clipped

Karolinn Fiscaletti

A bird my own color lights next to me.

“Did you cheat?” she asks.

No, I say

I am honest

because I am honest.

But as I watch the invisible wind

grasp her and lift her

far above me and away,

I can feel that leaden truth

touch the bottoms of my feet, now still.

I want to expose it,

to call after her

with another word,

but I do not understand her language.

I have only learned to memorize the pleasing answer.

Threads

Karolinn Fiscaletti

The heat is alive today.

It rises in waves

from the web of white tiles she

is stuck to.

Today his eyes say

that she has no choice.

She does not meet them,

but looks up

at the shadow of the still fan,

sprawled

like a spider

against the pale yellow ceiling.

Coffee

Kristen Shaul

A famous Dominican musician once sang, “I hope that it

rains coffee.” I can’t help but hum the tune as I sit holding a cup

of the steaming liquid in my hands. Across from me, a darkskinned man with bright eyes sits on a plastic chair, sipping his

own cup of the strong brew. Blistered hands and worn clothes

reveal that he is both hard working and poor. But in spite of his

humble appearance, Frances leads an extraordinary life in which

he cultivates an immense supply of one of humanity’s most

desired and loved substances. Frances is a coffee grower, and he is

devoted to raising and harvesting the beans that keep the world

awake.

Frances’s family has resided in Los Montecitos, Dominican

Republic, for four generations, and coffee has always been a part

of their lives. The family owns thirty acres of land located in a

small valley where an uncommon mix of towering pines and

great fruit trees dots the landscape. Underneath the canopy of the

tall trees, thousands of coffee shrubs cover the earth. The small

evergreens huddle together in the shade, their glossy green leaves

shimmering in the indirect sunlight. Frances spends several days

a week walking among these shrubs. He prunes, waters, fertilizes,

and lovingly cares for the plants that support his family. When he

is not working with his coffee, Frances spends time in a section

of his land that is used for growing crops such as beans and peas.

He leads me through the small plot and explains how the crops

provide food as well as income between the coffee harvests which

happen once a year. I notice the perfect rows of flowering pea

bushes and how their delicate branches bend under the weight of

heavy green pods. Frances smiles and says, “They look good now,

but you wouldn’t want to see them when the coffee is ripe!” He

notices my perplexed look and explains, “Coffee is king. When

the coffee is ready to be picked, I don’t pay any attention to this

part of my land!”

In the cool of early November, the coffee plants burst with

red cherries, and the entire town disappears into the shrubs to

collect the firm and shiny fruit. Frances states, “The town really

comes together during harvest, and everyone helps each other.”

Men, women, and children use old belts and bits of rope to strap

tin cans around their waists, and they sing and joke as they make

their way through the valley. Their experienced hands move

quickly, and an entire shrub can be stripped of its fruit within

minutes. The cherries are plunked into the tin cans which, when

full, are emptied into large canvas sacks and transported back

to town by donkey, horse, or motorcycle. During the winter

months, Frances oversees the harvest on his land and then helps

his neighbors with their own coffee. Harvest continues until late

January, and every day is spent among friends handpicking the

fruit that is the livelihood of nearly every family in town.

As we make our way back to town, Frances points out

a large metal grinder that stands about five feet tall. He says,

“This is the first stop for a newly picked coffee cherry.” A large

crank juts out of the side of the grinder, and Frances gives it a

turn to demonstrate how it works. Huge wheels begin to turn,

and the sound of metal scraping against metal causes me to

cringe. Frances explains how the coffee cherries are dumped into

the grinder where the beans are separated from the pulpy red

exterior. He gives the grinder a little kick and says, “I love coffee

growing, but this part makes my arms hurt!” During harvest, he

spends several hours a day turning that metal crank. The task is

physically daunting, but the result is a pile of white beans which

are nearly ready to be transformed into the perfect cup of coffee.

Once they are run through the grinder, the beans are

soaked in buckets of water to remove any remaining flesh. They

are then piled onto large tarps which are spread across the town’s

single road. The beans will stay out in the sun for about three

days until they are completely dry. As we walk down the road,

I watch my step and maneuver my way through the tarps and

piles of newly picked coffee. I soon notice that Frances’ beans are

being trampled on by everything from chickens to motorcycles,

and I can’t help but wonder if the coffee I drank earlier had been

walked on by a hen. Oblivious to my thoughts, Frances continues

his explanations about the drying process. He tells me that

most of the dried beans are placed into sacks and sold to a large

company that will roast, package, and ship the coffee to stores

all over the country. Though most of his coffee is sold after the

drying process, Frances keeps hundreds of pounds of dried beans

in the back room of his house. He will roast and sell some of it

to friends in nearby towns, but most of it will be consumed by

his family. The stash of unroasted beans will stay good for up to a

year and will provide his household with a constant source of rich

flavor and needed caffeine.

Frances asks if I would like to see the roasting process, and

I nod enthusiastically. He leads me to a small wooden shack

behind his house, and I watch as his mother dumps the coffee

into a metal caldron situated over a low burning fire. She stirs the

beans with a large wooden spoon, and I observe as they slowly

turn from white to brown. A rich aroma soon fills the air, and

Frances smiles and crinkles his nose at his mother when she

asks if the beans look done. I assume that his response means

no because she continues to stir for another five minutes until

the beans are nearly black and look as though they are about to

burn. Frances smiles and states, “I like it strong. The darker, the

stronger.” His mother removes the beans from the fire, lets them

cool, and dumps them into a partially hollowed out tree trunk.

She then reaches for a large, smooth piece of wood that is shaped

like a baseball bat and spends the next thirty minutes crushing

the beans by hand until they become a fine powder.

After observing the hour long process of roasting and

grinding, Frances and I return to his house with a bag of rich,

dark coffee that is ready for brewing. Frances’ sister takes the bag,

puts some of its contents into a metal coffeemaker, and turns on a

small gas stove. As the coffee brews, I listen as brother and sister

talk about friends, neighbors, weather, and happenings in the

town. I smile when I realize that, at some point, all conversation

returns to coffee.

To Frances, coffee is life. Most of his days are spent caring

for the shrubs, and in the evenings, his family sits outside with

mugs of the freshly brewed liquid in their hands. Frances hands

me a cup, and I can’t help but close my eyes as I drink. It is

delicious. He smiles and says, “I am glad you like my coffee.”

Frances is proud of his work and says that there is nothing else

he would rather do. As I pull the cup to my lips for a final sip,

I think about how what I am drinking was planted, picked,

cleaned, roasted, and brewed by the man in front of me. I can’t

help but think about how coffee keeps millions of people awake

and moving and how workers like Frances are the humble force

that supplies the world’s favorite drink.

Checkmate

Nick Jeanetta

The plantation owner sat on a thin cane chair in the oasis

of shade his long front porch provided. It was summer, and his

thermometer had long ago exploded. He scooted his chair closer

to the small, rough-hewn table in front of him. The teak boards

beneath the worn leather soles of his handmade shoes were

smooth, almost polished. They were spaced generously, designed

to let the daily crush of Brazilian rain through, and reminded

him of the ribs of a crocodile carcass he had seen as a little

boy on his family’s annual trip down the river from Manaus to

Belém. Before him, on a burnished silver tray, was a chilled 600

ml garrafa de cerveja and two small glasses, also chilled. A peeled

but still whole orange was nestled in an exquisitely blue porcelain

bowl next to the beer. In the center of the table was a chessboard,

painstakingly carved from a single plank of ironwood—

burnished to perfection. The wood seemed to ripple as light

reflecting from the bottle played tag on its gleaming surface.

The game was half over. White was losing. That f***ing

Rook at c5. The man wasn’t particularly good at chess; he often

lost, but he loved the game. It made him feel cultured. The seat

across from him was empty. It was Black’s turn. He ponderously

separated his orange, enjoying the slow tearing immensely. A

silver ring, embossed with an intricate tarantula, clung to a thick

finger. He had big hands. They had once been covered with

calluses, but rich living had long ago made them soft. All the

little cuts and injuries he had worked hard to earn were now

faded scars. He began absent-mindedly twisting the ring. Where

was Colonel Silva? It wasn’t like him to be late. Perhaps he had

been summoned by the General for some last minute strategy

meeting. Colonel Silva was one of the best strategists in Pará.

Maybe he was helping with the manhunt. Silva had phoned him

late last night about the enemy helicopter that had been shot

down. Apparently, a junior analyst had deciphered a message

about an assassination attempt on the General—a sniper was

going to be flown in by helicopter under the cover of darkness.

The base had upped security and placed anti-aircraft missiles at

key positions in the jungle. The helicopter had been shot down,

but only the bodies of the two pilots had been recovered. Every

soldier stationed at the base was now fanning out through the

jungle, each one wanting to be the first to find and capture the

missing assassin.

A light breeze rippled through the stretch of cane fields in

front of his estate. The resonant sound of his sugarcane clacking

together was almost melodic and had lulled him to sleep every

night of the growing season. Lost in thought, he didn’t notice the

lone figure walking through his field until he was just a few yards

from him. With wide eyes he appraised the filthy and exhausted

looking man. The custom sidearm rig strapped to his right thigh,

complete with decidedly not-standard-issue revolver, and the

mud splattered but still visible patch on his left shoulder gave

him away.

He grinned at the panting assassin. In his condition, he

didn’t look like he could kill a cockroach, much less the esteemed

General. He was holding his bleeding left arm close to his chest,

and it looked as though a splinter of bone was pushing through

his skin. That had to be excruciating.

“So, are you the assassin everyone is looking for, my friend?”

The plantation owner’s voice had been sanded smooth by

years of cigars and scotch. The man just stared, unblinking, from

under hooded brows.

“Please, come sit. You must be tired.”

The man approached his porch like a dog with three legs,

took each broad stair individually, and finally collapsed with a

groan into the chair opposite the plantation owner. That close,

the soldier’s stink was overwhelming. The plantation owner

pressed his handkerchief against his nostrils. With his other

hand, he slowly reached over and poured the man some beer.

“Please, drink.” He grinned broadly. “My hospitality is

legendary.”

The soldier couldn’t contain himself. His right hand shot

out, brought the cup to his lips, and drained it down his parched

throat in one smooth motion—like a cobra striking a rat. The

plantation owner didn’t have time to recoil in shock. He was fast.

Hand trembling slightly, he moved to refill the assassin’s cup.

The soldier accepted the beer in silence. He took his time with

this one, sipping the bitter liquid like it was ambrosia. His eyes

flicked around, taking everything in, too fast for the plantation

owner to follow.

“Do you need someone to play with?”

The soldier’s voice was quiet and higher than the plantation

owner thought it would be. He licked his lips and swallowed

before answering.

“Well, actually, yes. I believe my opponent is busy searching

for you.”

That brought a thin-lipped grin to the assassin’s face.

“I see. Then, as it is my fault he isn’t here, and as you have

shown me great kindness already, it would be dishonorable of me

to leave this game unfinished.”

The plantation owner tipped his head slightly in

acknowledgement. He wondered if he would escape this

encounter alive. Sweat dribbled down his brow in innumerable

rivulets. Where was Colonel Silva?

“It would be my honor.”

Colonel Silva would probably show up soon, despite not

finding the assassin in the thick jungle. He had never been more

than an hour late to their weekly chess sessions. What would

happen? Would the man start shooting? Would Colonel Silva?

The plantation owner swallowed again.

“It is Black’s turn.”

The soldier nodded and focused intently on the board in

front of him. He sat deathly still and said nothing for a full ten

minutes. The plantation owner began to fidget uncomfortably.

His back was starting to sweat. When the man finally moved,

it was slowly and deliberately. He picked up Black’s remaining

knight and moved it to g4. The plantation owner froze. What was

he thinking? That was the worst move he could have imagined.

It left Black completely vulnerable, not to mention forfeiting his

knight in the process. He shook his head slowly and hesitantly

captured the knight with his pawn. The soldier didn’t move a

muscle until his knight was off the gleaming battlefield. He

smiled sadly. The game proceeded quickly after that, piece after

piece leaving the field of play. The plantation owner didn’t realize

the depth of the soldier’s trap until it was too late.

“My God,” he murmured, bringing his hand to his lips. “It

was perfect… I lost the second I took that knight.”

The soldier smiled that sad grin again. It was indeed perfect.

No matter what move the plantation owner made, he would

lose. Every single Black piece was set up to checkmate White’s

king. The plantation owner leaned back heavily against his

chair, mopping his brow and shaking his head in disbelief. The

sharp click of a rifle being cocked startled him out of his daze.

He looked up in surprise. Colonel Silva stood ten yards away,

automatic rifle aimed squarely at the assassin’s back.

“Stay where you are. If you even blink too quickly, you are a

dead man. Are you all right, my friend?”

The last was directed at the plantation owner.

“Yes, yes, I am quite all right. I have never been more

soundly defeated in a game of chess, though! I think he might be

better than even you, Silva!”

Colonel Silva grinned from behind the iron sights of his

weapon.

“And yet, I am holding the rifle. You can come out!”

The assassin sat unmoving, grinning sadly down at the

chessboard as thirty of the Colonel’s men filtered out of the cane

field, weapons trained on the lone soldier’s back.

“We’ve got you surrounded. Don’t try anything stupid.

Daniel! Please remove the prisoner’s pistol.”

The heavily sweating young soldier inched towards the

cornered prey, rifle tightly gripped and shaking. The plantation

owner could see him hold his breath as he reached a trembling

hand out and removed the assassin’s revolver from its holster.

He let out his breath in a great rush of relief as he jumped out

of reach of the wounded man. Daniel looked almost cocky as

he strutted back to his comrades. He had a souvenir and a story

his two sons would love. Colonel Silva looked at him out of the

corner of his eye with amusement.

“Daniel, radio the General! He will want to come see his

‘assassin’ immediately!”

The assassin just sat in his chair, grinning sadly

It took fifteen full minutes for the General’s jeep to roar

up the road leading to the plantation owner’s house. The jeep

crunched to a halt on the white gravel drive, and the General

stepped out, patent leather boots gleaming. He clenched a thick

cigar between his ivory teeth, and his mirrored sunglasses spit the

world back at its own face. He grinned, gravel shifting under his

heavy steps, as he approached his would-be killer.

“It seems things did not go so well for you,” he drawled at

the captured man. “Turn around, so I may face the man sent to

kill me.”

The soldier stood up slowly, wincing in pain. He turned

around. His cold eyes stared through the glasses into the

General’s soul.

“I have something for you, sir.”

The General’s eyes widened behind their flimsy protection.

“Oh? What is it?”

The soldier reached down slowly, slowly, and pried open

the clenched fingers of his left hand. He pulled out the thin,

bloodstained GPS chip—the red LED flashing urgently. He

tossed in on the ground in front of the General.

“I was the Knight,” he said, grinning sadly. “Checkmate.”

The Tomahawk missile dropped from the sky, detonating

right before it reached the ground. The General didn’t have time

to scream.

The Carpenter

Vera Lynn Petersen

A film of sawdust fills the air

as he shoves the wood past the bright

spinning blade. Muscles flexed, back bent

over, determination on

his face. A hint of the scent of

Bonfire scatters across the wood

shop. The eerie noise of grinding

ceases as the plank hits the floor. He

looks up from the stopped blade at his

perfectly cut piece of dark black

Walnut. He imagines what it

will become, how every grain will

fit into the pattern of his

artwork. I watch him smile and say,

“By the work one knows the workman.”*

*Jean de La Fontaine

At Your Two-year-old Pace

Elizabeth Schooler

I am your shadow while you

pick up little pieces of the world.

We feel the fresh wind breathing

on our bare hands.

You shiver and grab a maple leaf,

bright red with fall—to unite

with the other new-found treasures

in your pocket. You spot a worm,

still and stiff, and demand

he wake up before adding him

to your collection.

The Confession of a Mask

Dedicated to the late Yukio Mishima

by Luis Salinas

The shoes of hundreds of pedestrians strum the winding streets. They etch out a dull staccato that resonates in between heavy stones of the aged city of La Paz. The wind-burnt faces of native women shout the sale of their alms, from knick-knack dolls to street foods such as hearts on skewer or chicken filled-bread pouches. Further, into the downtown business district, men in suits pull their corbatas tighter. It seems that if they didn’t, their barely fastened porcelain faces might fall off and shatter their pretentious privilege. Some of these men descend upon the street and collect their daily packed lunches from those same native women that shout into the air.

A sea of faces fits into only a handful of types that include features of European extraction to those more Amerindian. Slight distinctions, real and perceived, form cultural fault lines. Everyone appears so similar yet imagines themselves so different. Merchant women in their shawls and derby hats, business men in their blazers, children working or begging, and the street youths in worn jerseys are readying for a protest. They are all bound to an assumption, to an archetype, that has over time been sewn into their costume. As if through their live-or-die industriousness, the street people have completely become that glance until their faces are as cheap and plain as the dolls that the market women put on display.

Yet among this handful of living statues and motile poses, there is one that slips through. The one whose face stays unique because it is always hidden. The face without a face. The one who wears the mask. He is found on the corners near the buildings where those same European businessmen let out from work. He waits and silently breathes in that polluted air through the meshed cloth that wraps around his face. He is not a beggar, and he does not want to be seen. Instead, he prays for invisibility from those who don’t desire his service.

The faceless man is distinguished by the old off brand ‘Adidas’ jumpsuit he wears. His hands are covered in gray until the seams of the gloves, worn from work, break and his copper fingers escape through. His feet are covered with red imitation Chucks with more than a few holes from walking miles in them, day in and day out. His face is covered by a green balaclava mask, the kind that bank-robbers and special forces wear in Hollywood movies, except this one comes from dyed llama wool via Bolivian army surplus.

Yet there is nothing fantastic about his work. A business man sets his foot on the pedal atop the young man’s improvised shoe-shining kit. In front of the young man’s masked face, within the wooden box, is an aged brush and various colored polishes. He pulls them out from a surprisingly well-designed drawer that comes out of the bottom. He directs himself and his instruments toward the shoe. The smell of rotten petrol filters through the mask and into the young man’s nose. Cheap South American leather is made of that bovine flesh bathed in the spent blood of the farmer’s tractor. The oil is thrown in a barrel and set aside just for leather softening. He is reminded of this every time he works for his coin. He quickly scrubs with the brush and black polish and continues to breathe the smell of lacquer and oil. He will not turn his face from the smell because, no matter what, he knows the smell will never become a part of him. In the same way, when eyes gaze down upon him, he won’t give them a glance back up.

In this transaction, he gives his hands but not his heart. He gives his minutes but not his mind. He sells his service but never his self. The businessman in his cheap knock-off Italian suit asks his name: “Como te llaman?” He thinks. He could tell him his name, but then what next? He fears perhaps the wind might steal his voice and tell everyone the name behind that cloth-shred of dignity.

The only shoe-shiners whose identities are known are those who wear no mask. They are shoe-shiners their whole life and make it a profession. Often, they are drunks and drug addicts, laughing for their clients and rotting for themselves. Many of them make more money because of this, because people don’t feel it so intimidating nor so awkward as dealing with a man without a face. Maybe. Or, perhaps, they simply pay for that unfortunate spectacle. They desire to see one naked of dignity and decaying of self-worth. That sort of sadism that gives a hard but foul shot of power and then washes it down with a swig of artificially-sweetened false charity. The name of that liquor is the unmasked shoe-shiners’ baptismal one. Through pouring it out, he sells a little piece of his soul to any anonymous soul that throws him a dime for it.

The masked shoe-shiner realizes that this drunk was once like himself until the day he gave up hope and gave his name. Step by step, he must have lost himself, first his name, and then his mask. For a second, the young shoe-shiner thinks to invent a name. “Ricardo” almost leaves his lips, but he stops himself. He thinks, to put a name to the mask, is to become someone other than a shoe-shiner. If the mask is not him, then how can it be anyone else? The name he might say to this man would be the vocals that pronounce his person until he has a face. So he decides. He will sell the man a cleaning, but he will never sell him a confession.

“Disfraz.” He refers to himself as a “Mask.” The man responds, “Well, then I believe we know each other already.” He throws a cheap coin onto the ground and walks away. Why does he hide himself? Shame. He doesn’t want to be recognized as he prostrates on his knees and shines the shoes of businessmen and oligarchs who look down upon him. So he wears his veil–to break that connection between those whose bellies are so full of themselves and the food cooked by the masked man’s own mother.

He shines on for hours but never dares to look into the eye of the ones that throws him the coin. Disfraz continues both as silent and faceless as a living silhouette. He is dignified, yet shameful. He is both the screaming mute and the voiceless siren. Hardly anyone looks, and he is relieved.

As dusk breaks, the businessmen pile out of the buildings and loosen their ties. He knows they are eager to be home so they will not stop for his service. Even without ties, they are still business men. He decides the day is done. He packs up his modest tools and stands. The ache of kneeling climbs up his back thigh, and he reaches towards his toes to stretch it out. He walks to the bus stop among a crowd of street youths, now shirtless from the sweat of playing soccer and boards. He keeps his mask on. Even without shirts, they are still street youths. He gets off at his stop, some miles from his home in the heights where the city walls having only started their change from concrete into adobe. As he walks, he sees a merchant-woman remove her derby hat to fan herself. Yet he still doesn’t remove his mask. Even without her derby hat, she is still a merchant-woman.

He approaches the comuna and turns right into the empty church on the corner. He is not religious, but he was trained to kneel, so when he enters he does. He thinks it is the least he could do for using the building everyday. He meanders in the darkness only lit by the dying sun through amateur stained glass. A crucifix is illuminated by the refraction of murky blue and purple glass. On this cross, a brown-haired and blue-eyed Christ dies eternally in his nudity. Disfraz walks towards the confessional. Even without his clothes, Jesus is still Christ. He looks around once more to make sure he is completely unseen. Then he pulls the latch on the flimsy confessional door and seats himself facing the mirror with the woven cloth porthole of penance to the left of his face.

He looks at the green face in the mirror, and the heavy almost black irises seem to pierce back into him. He recalls on the bus, a young boy reading a comic book, and the masked avenger on the cover. He knew the hero as well. He read it once, before his father died, back when he had time for such things. He recalls the superhero would go into a phone-booth and change his clothes to become a man capable of saving the world. He smiles and notices in the mirror that he can hardly tell it aside from a ripple in the thick woolen cloth. He thinks about how, despite the mask, he is so unlike this Superman. If he were, what would be his superpower? Shoe-shining? He looks at himself longer. He thinks about the man who asked him his name. He looks down at the floor with its simple red carpeting, and then he looks up and says, “Disfraz.” He almost doesn’t believe himself as he pronounces the words. Is he a mask or a man? He wants to say his own name, his real name, and he begins pursing his lips to make the sound. His vocal chords will not sound. He begins to cry in the silent Indian way when the heart grows heavy, and the jaw grows stiff.

He clenches the green cloth from the back, and he looks down to avoid catching the transformation. He wrings it upwards as if it were a noose killing the man he just was. He looks up to the mirror to put on his flesh once again. Those same piercing irises look back, except this time with utter honesty. He sees jet black straight hair, a powerful condor nose, a long slender face, slit Asiatic eyes, and due to the sun, skin as red as the thousand years conquest of the Inca. He leaves the dark church and strolls the dusk streets towards his home. Some men recognize him, and they shout, “Hey, wanna-be, wanna-be lawyer! You gonna get me outta jail when I go?” in the native tongue that he too understands. In that instant, they both laugh at but encourage his humble dream. He then stops by some merchant-women and buys some morsels for dinner.

He walks some blocks further onto a large cinderblock construction with a metal roof. He enters one of many doors, and a little boy recognizes him immediately and runs toward him. Even though the man’s hands are full, the little boy reaches high and tries to climb his leg, He hands him the bag and notices how filthy his fingers are. He scolds him to wash up and kisses his head. The boy sets down the bag and is pulled across the packed earth floor to the simple spigot and mirror in the back of the two-room quarter. The man runs the water and sees the dirt and dust break from the fingers and their innocence slowly return. The fingers are so small and slender and yellow like parched blades of grass before spring. He releases the boy, and the boy stares in the mirror at the man’s matted hair and sweaty skin. The man washes the face seen by the boy who loves him and never asks where his pocket full of coins comes from. Without his mask, the man becomes the little boy’s older brother.

The man then laughs about the comic book hero to himself. He thinks, if he had a superpower what would it be? Spanking little brothers…? Legal ability? He says to himself, “Esperanza,” the word for ‘hope’ in Spanish. The water runs as he thinks… but his trance his broken by the voices of two boys. Through their shouts they finally grant him his name.

A Summary and Response to Dickinson’s “I heard a Fly buzz”

by Tonja West

When we think about a fly being near, the majority of us swoosh it away, as an outsider never belonging in our presence. I admit I have many times; the fly has resembled a nasty sort of insect that I never wanted around. It wasn’t until four months ago that I experienced a different viewpoint on flies. My uncle Neil, who was diagnosed with lung cancer, had only a couple months left to live. After we planned what we thought would be just the first of many visits with Neil, it was sadly our last. In the comfort of his home, Neil spent his last days. He was not alone during his final days; he was accompanied by what seemed to be a buddy, a comforter for Neil, yet an annoying indestructible fly to those in his room.

The sound of the buzzing fly, the inconsiderate interferences as we were holding on to the last moments of Neil’s life annoyed those at his side, yet never seemed to bother him. As the fly rested upon his arm, face or head, Neil never budged, never moved a muscle. Laughter filled the room amongst his loved ones, as we were certainly bothered by the fly. Dickinson writes, “For that one onset – when the King Be witnessed – in the room,” (7-8) is interpreted as an angelic comforting form present in the moment of death. I believe the fly in Neil’s room represented for all us, his loved ones, that an angelic form was present with him in that dying moment, which we were able to see with our naked eyes. There seems to be something with our dying loved ones during their last moments, some kind of peace. But we are never sure because we are unable to see or experience what the dying person is able to. The fly, however, we were able to see. The first line of the poem Dickinson writes, “I heard a fly buzz – when I died,” the buzz being a tangible thing in the moments right before death. When all else physical begins to fade, the tears, the loved ones and the possessions once owned, the fly is the last to go from the one dying. (5-12) “There interposed a fly,” separating life and death. Death finally arrived, all else is gone. A final goodbye for the deceased and the surviving loved ones, the sound of the fly buzzing was life’s separating point. Once my uncle Neil passed away, the fly was no longer noticeable among us. The fly was gone, bringing a lot of curiosity.

This poem by Dickinson surfaced something real within me. I had thought a lot about the last moments of my uncle’s death. Was he in pain? Did he feel that last breath as I witnessed it, with much pain? When did he separate reality with death? Was someone with him in those final breaths? Reading this poem has calmed the frequent and frightening thoughts that have haunted me for months. Maybe that fly was some angelic form comforting him in those last moments. Perhaps Neil had separated long before his last breath, relieving him of the pain. I’ll never know for sure, but reading something where a fly was such a profound comforter in the last moments in the process of death elsewhere gives me more comfort in knowing my uncle Neil was not alone. The determined commitment of the fly that brought us so much laughter in a time of deep pain and sorrow was also the comforting gift of presence from my uncle to all of us. This poem represents what could be closure for us, those left behind.

The “Fat Tax” Issue

by Kelly Miskimins

Obesity is an escalating problem in America. Much like smoking, obesity creates health risks and can even lead to death. To help alleviate the obesity problem, reformers have called for a “fat tax,” also known as a soda tax. The “fat tax” would put an extra tax, or sin tax, onto fatty foods, such as soda. A “fat tax” is a necessary step in helping to reduce the number of obese men and women in the United States because it will decrease the demand for sugared drinks, lower the intake of sugared drinks, and put more money into government-run programs.

According to Daniel Engber, a journalist for Slate magazine, the idea of the “fat tax” has been around since the attack on Pearl Harbor. The idea of a “fat tax” was a little different at that time. A physiologist by the name of A. J. Carlson wanted to tax overweight people themselves. For each pound a person was overweight, he or she would be taxed a certain dollar amount. The idea was that the extra money would be used to help support the ongoing war at the time (Engber). Today the idea of a “fat tax” is different, although some people still feel that overweight people themselves should be taxed directly.

Instead of taxing obese people directly, experts believe that taxing fatty foods as well as sugared drinks, such as soda, will help reduce the number of obese people in America. The idea of a “fat tax” is similar to that of raising the price of and taxes on cigarettes to dishearten people from buying cigarettes. In this case, people will be discouraged from buying sugared drinks because it takes more money out of their pockets to purchase a substance they do not necessarily need. The belief is not that people will stop buying sugared drinks, but that ultimately they will buy fewer of the taxed items. According to Joseph Brownstein, a reporter for ABC News, the hope is, also, that taxing sugary drinks will help fund “government-run health programs” by letting these programs use the increased income that is generated from the tax (Brownstein).

Although the “fat tax” is popular with state legislatures, it is not so popular in Congress because, according to Brian Wingfield of Forbes magazine, the majority of Congress feels that taxing people will not help in making them healthier (Wingfield).There are also other opponents to this idea, such as Patrick Basham from the Cato Institute, which is a think tank located in Washington D.C. Basham wrote an article stating five major reasons he believes the “fat tax” will not work. One of Basham’s strongest arguments is that there is no significant scientific proof that “sugared drinks” are a leading cause of obesity. Although there have been many studies by organizations, including the Center for Disease Control, that show sugared drinks as the number one cause of obesity, Basham claims that these results are merely assumptions. He goes even further, saying that “design flaws” in the study made it hard to determine whether the change in weight was due to the sugared drinks or the actions of the participants (Basham).

Basham also believes that the “fat tax” will have “perverse, unintended consequences.” One study has shown that people that are less well off simply consume fewer healthy foods in order to buy the less healthy foods (Basham). Although Basham’s concern is valid, if a tax were implemented those consumers would be able to buy less of the sugared drinks than before. The increased price would mean that their dollar would not go as far. Thus their intake of sugared drinks would still be reduced.

Andraz Melansek, from the Internationa! Debate Education Association, who posted on Debatepedia, which is an organization that gives both sides of international debates, says that a “fat tax” “distances individuals from consequences (debatepedia). This means that, instead of making the consumer responsible for his or her own actions that lead to obesity, he or she can simply keep the same behavior, just at a higher cost. Furthermore, everyone in society would have to pay a higher price, not just people with weight control issues.

Though the opponents to the tax have valid concerns, the numbers and studies are not in their favor. The studies say, and other experts agree, that sugared drinks are a leading cause of obesity. According to Anemona Hartocollis of the New York Times, in the small borough of Staten Island alone, 65 percent of the residents are obese and overweight. Of these residents, 35 percent drink at least one or two cans of soda or other sugared substances daily. This excess of sugar is adding to their weight problem (Hartocollis).

Doctors, such as Dr. David Ludwig, who co-wrote Optimal Weight for Life, and former New York health commissioner, Dr. Thomas Frieden, both agree that a “fat tax” would help reduce the number of obese people in America because of all the sugar soda and other sugared drinks contain (Brownstein). They are not saying sugared drinks are the only cause of obesity, simply one that can be reduced while bringing in money for the government.

It is true that each individual should be responsible for his or own health. However, when the majority of society has a similar health issue, it is time to take action. Catherine Rampell of the New York Times reports that 28 percent of American adults are obese and another 68 percent are overweight (Rampell). This means that 96 percent of the American adult population has a weight control problem, which puts an economic burden on the country due to increased sick days and health care costs for these people. Because this is a very prominent issue affecting most of society, action is needed. Although people do not generally support being taxed, sometimes it is necessary and effective. A good example of an effective, but straining, tax is social security, which many people depend upon.

Much like the social security tax, a “fat tax” will bring in more money for the government and can be used to help support government-run health plans (Brownstein). Because obesity is a health problem, it makes sense that the money made from the “fat tax” is used to support healthcare because obese men and women are big consumers of the healthcare system. According to Dr. Richard F. Daines in New York, the intake of soda could be reduced by as much as 15 percent if the tax were implemented. Moreover, the tax would be able to bring in one billion dollars yearly for the state of New York (Hartocollis). Trevor Griffey of Olympia News reports that fights to implement the tax are being fought in other cities and states as well, and one was won in the state of Washington.

Although opponents to the tax, like Patrick Basham, believe that the tax would not work for many reasons, the numbers disagree. According to the Center for Public Integrity, some soda companies have spent around 24 million dollars lobbying against the “fat tax.” That amount of money was spent in less than a year. The soda companies would not profit from the extra tax, but, because the tax only applies to sugared drinks, they would still have the revenue from their diet drinks or drinks with sugar substitutes, the sale of which may increase due to the lower cost. Moreover, the tax would not take away all of the revenue for sugared drinks, simply reduce the amount sold. According to Trevor Griffey, if there were a nation-wide tax of three cents per every twelve ounces of soda sold, in a period of ten years approximately 24 billion dollars would be made . This money would help support healthcare (Griffey). Healthcare is an important industry that needs much support due to the recent economic downturn. The money made from the “fat tax” could be just the support the healthcare system needs.

People are comparing the “fat tax” to the sin tax on cigarettes. The cigarette tax has been followed up by studies that prove its success. Economics of Tobacco Control found that by raising the price for one carton of cigarettes led to a decrease in demand for cigarettes by four percent. Although the cigarette companies suffered slightly, in the end they came out unharmed and just as stable. Thus it is likely that the soda companies would as well. The tax would not prevent people from buying soda or other fatty foods. It would simply limit the amount people could afford to buy, which would in turn lower their sugar intake. This means that the demand for soda and other sugared drinks would decrease in the same fashion as the demand for cigarettes.

Every person is responsible for his or her own health. If people are not willing to take the steps necessary to be healthy, though, perhaps it is time to assist them in this endeavor. No, the “fat tax” will not completely solve the obesity problem and, like any other system, it has its faults. However, it is the first of many steps that can be taken to help control and reduce the number of obese people in America.

Works Cited

Bashman, Patrick et al. “Hard Truths about Soda Taxes.” Cato Institute. 6 July, 2010. 10 Oct. 2010. Web.

Brownstein, Joseph. “Public Health Leaders Propose Soda Tax.” ABC News 17 Sept. 2010. Oct 6 2010. Web.

“Debate: Fat Tax.” Debatepedia n.d. 4 Oct. 2010. Web.

Hartocollis, Anemona. “Health Official Willing to Go to the Mat Over Obesity and Sugared Sodas.” New York Times 4 Apr. 2010. 10 Oct. 2010. Web.

Soda Tax Debate.” Olympia News 20 Mar. 2010. Web. 10 Oct. 2010.

Tone and Style in Sylvia Plath’s “Daddy”

by Sara Wilson

Throughout “Daddy,” by Sylvia Plath, the tone varies from childlike adoration and admiration to that of a contemptuous and detached, yet fearful adult. The tone is found to be innocent, almost akin to a lullaby at times, and incredibly manic and sinister at others. Unlike her variations in tone, Plath manages to maintain a dark and heavy style throughout the poem through her use of diction. “Daddy” is a confessional poem, presented in an oppressive, negative manner, not unlike much of Plath’s work. With all that is known about Sylvia Plath and her short life, one would expect her experiences to reflect in her work in the form of her signature tone and style.