2007 Issue

2007 Writing Awards and Selections for Print and Web

For her essay “New Year’s Day,” Angel Dewaele is the winner of The Metropolitan 2007 Prize for Student Writing, a 12-credit-hour tuition remission. The first runner-up, Daniel Otto, is awarded 9 credit hours tuition remission for his poem “How to Make a Soup Sandwich.” The second runner-up, Tara Novak, receives 4.5 credit hours tuition remission for her essay “Sun in the Sandhills.”

New Year’s Day and Tolerance and Community by Angel Dewaele

How to Make a Soup Sandwich: (a list of things I love about Iraq) by Daniel Otto

Sun in the Sandhills by Tara Novak

Colorism by Nicole Upchurch

Poor Relations by Zedeka Poindexter

The Artist by Brooks Utterback

Stone Critics by Hoken Aldrich

The Battle of River Run by Catherine Burghart

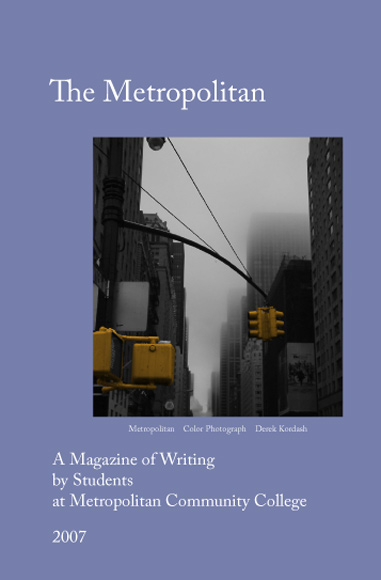

Metropolitan (cover photograph) by Derek Kordash

Field #4 (cover photograph) by Steven Schmiedeskamp

Additional Web Selections by Promising Writers

Dead or Alive by Jason Jablonski

The Historical Significance of Kanosha, Nebraska by Patricia Sedlacek

Ole’s Shoe Repair Shop: Not Just for Toni Lama or Manolo Blahnik by Dottie Smith

MetroReads! Spring Contest Winners

I Am From… by Sara Jackson

I Am From by Christine Porter

MetroReads! Winter Contest Winners

I Am From by Bethany L. James

An Underdog’s Reward by Elizabeth Denburg

*Honorable Mention: We Are From… by the class of ESLX 0130 8A (Winter 2006)

New Year’s Day

Angel Dewaele

What am I going to do? What is it doing here? What am I

going to do?

I couldn’t move. My feet refused my commands (turn

around, get out, leave). I had just gotten home and come into

the kitchen to check my messages, and now my panic filled the

room. A half-full bottle of warm, honey-colored liquid had my

complete attention. It screamed at me to pick it up. I had no

choice but to stay. I belonged to it.

Damn. I love whiskey. Damn.

Why is it even here, in my own apartment? Shit. I had

somehow managed to avoid booze for the last six months.

Okay, maybe I had cruised the cold medicine aisle for Nyquil

even though I didn’t have a cough, stuffy head or fever to treat,

but, still, I hadn’t taken a drink since summer. Oh, that’s right.

Chuck’s brother, Brent, is in town for the holidays. They like to

have a few drinks and get a little loopy when they get together.

This must be the leftover booze from last night. Leftover booze.

That’s funny.

I grabbed the bottle from the top of the fridge just to shut

it up. The weight of the whiskey bottle felt good in my hand. It

felt right, like home. Like I could breathe again.

The kitchen faded around me: the new linoleum marred by

an errant Fourth of July sparkler lit inside last year, the stained

glass piece that Jodi made hanging in the window, glowing blue

with the midmorning sun, the photo of Brent donning a sleazy

pencil-thin mustache he grew specially for his graduation on

the refrigerator. Images from my non-using life raced through

my mind: my friends, my girlfriend, my nieces, my cats. I saw

everything I value, everything I love. Everything that is me. I

instinctively knew I would lose my life, piece by piece, if I took

even one drink.

I unscrewed the cap.

The aroma broke free and stung my senses. I salivated. No

glass for me. I had spent a night a few summers before teaching

myself to drink whiskey straight from the bottle without so

much as a wince. Hey, a girl’s gotta have goals. I earned this

badge of a badass, and I wasn’t going to puss out now. I raised the

bottle to my mouth.

I remembered humiliation after humiliation: vomiting,

ditching friends, waking next to “what’s your name again?”

getting pulled over, wrecking my car, “coming to” under a tree in

the park. A lot can happen to a girl when she is a blackout drunk.

Christ. The problem with blackouts is that they don’t black out

enough.

Damn. Damn. Damn. I don’t want that. I hated that. My

life was miserable. All of the time. Except, that is, for the first

half hour of drinking. That was really the only time I felt like I

could live in my own skin. One half of one hour. Thirty minutes

of bliss. It came after I got the booze and before I lost any

control of what I was saying, what I was doing, who I was doing.

But whiskey (beer, tequila) tastes so good. And promises

so much. It promises to give me relief, peace, calm. It promises

to give me confidence, self-esteem. It promises me the ability to

interact with people without wanting to disappear. It promises

me that I will belong somewhere. It promises to rewrite my past

and give me the future of backyard barbeques, a loving family, a

successful career. And that I will become 5’8”, blonde and skinny,

attractive.

It lies.

I’m not one to hold grudges, though. I absolutely believe in

giving second (third, twentieth, sixty-seventh) chances.

This time will be different. This time I will be able to

handle it.

I am such a sucker.

I think of putting my tongue just inside the bottle opening.

Just touching my tongue to the rim, just getting a taste. I won’t

take a real drink. I just want to have some contact, any contact.

Standing in my kitchen, whiskey bottle in hand, I had

an awareness of how pitiful this is, how completely ridiculous

sticking my tongue in a bottle would look to anyone watching

this little drama. Normal people don’t stick their tongues in

liquor bottles. Normal people don’t want to stick their tongues

in liquor bottles. I am pretty sure of that. Don’t recall seeing

Chuck’s mother or father (or brother or sister or brother-in-law

or Chuck for that matter) playing tongue tug-of-war with the

Merlot at Christmas. And while his family grooves to its own

song of dysfunction (whose doesn’t?) they are pretty darn normal,

pencil-thin mustaches and all. Family, church, work and school.

Upstanding Midwestern citizens. Not an arrest among them.

I think I might be having a problem here.

I walked the three steps from the refrigerator to the table

in my small kitchen and placed the bottle on the vintage chrome

and laminate table top. Four gray fleur-de-lis reached, one

from each corner, toward the center of the table, breaking the

landscape of the gray and yellow speckling.

Shaking my hands, I tried to lose the sensation of the

whiskey bottle from my grip. I reached for the phone, checking

my messages, a forgotten task from my to-do list. I dialed Patty’s

number. I knew Patty was in AA, and I figured she might have

an idea of how I could not drink this whiskey right now. Hey,

Patty, got a coupla questions for ya. When is the best time to plant

tulip bulbs, what’s the first step in retiling the shower, and, say, you

got any tips on how I might not have to take a drink of this here

whiskey?

I wanted some sort of tip, a helpful hint. I needed a Heloise

of Hooch. Try hiding the liquor from yourself. Put it in the linen

closet behind the extra cotton balls and the guest towels. Or this one,

sent in by a reader in Ohio: I turn the television and/or radio up

REALLY loud, disturb the neighbors to drown out the demands of the

booze, and in a manic fit, alphabetize the M & M’s. Or, how about

this: Go shopping, get something to eat, start smoking, have sex.

Gamble. Punch a wall. Or cut. How about cutting? That’ll take the

edge off.

It would never occur to me to throw the alcohol away. That

would be wasteful.

“Hey, Patty, whatcha doin’?” I tried to sound chill.

“Hi honey! Happy New Year!” Oh yeah. I forgot. “Just

setting up my new TV. Alex is trying to figure out the remote.

What are you doing?”

“Um, I’m having a problem.”

“What’s up, sweetie?” Her tone was light and cheery. Ugh.

“Um, I came home and was minding my own business and

then all of the sudden I saw some whiskey and now I want to

drink it but I can’t and I don’t know how to not drink it when it’s

right here and I don’t know what to do.” Breathe.

“Listen, why don’t I come over?” I cringed at the thought of

her coming over.

“Um, oh..kayyy.” I didn’t want to be rude.

“I’ll be there in ten minutes.” Shit. I didn’t want this to be a

big deal or anything. Jeez.

I paced my living room, ineffectively tidying (pick up, put

down. pick up, put down) random clutter, trying to keep busy

until Patty arrived. I was both relieved that she was coming to

help and disappointed. Now I probably wouldn’t drink since she

was coming over. What was I thinking asking for help? Nuts.

“So where is it?” She was at the door. Man, she got here

fast. She looked like she had been having brunch at the country

club or had just come from a refreshing massage or playing

tennis. Not a care in the world. Bitch.

“In the kitchen.”

“Go get it.”

“You want the whiskey?” Uh-oh, is she falling off the

wagon? I don’t know about these AA types handling booze. I

hesitated.

“Go get it.” Dang. Bossy. I walked to the kitchen as Patty

sat down on my loveseat, the arms of the sofa shredded by my

two cats.

I gave Patty the bottle. She put it next to her purse on the

floor. I sat next to her on the loveseat.

“Patty, you can’t take that. It’s not mine.”

“Whose is it?” The bottle remained by her purse.

“Chuck’s.” Listen, lady, hand it back.

“He can have it back. All he has to do is call me and I’ll

bring it to him.” Well, that’s ridiculous. How am I going to

explain that? Yeah, Chuck, uh, listen. I know you had a bottle of

whiskey here at the apartment, but I spazzed out and couldn’t handle

being around it so Patty came over and I had to give it to her. No,

really, it’s not embarrassing at all. Real smooth, Angel. French silk

pie. Shit.

“So what’s the problem?” She was so nonchalant. Wasn’t the

world caving in?

“I want to drink that whiskey.”

“So, go ahead.”

I wasn’t expecting that. Hmm. Maybe these alcoholics

weren’t so bad after all. “But I can’t.” If I could, I would and we

wouldn’t be sitting here now would we?

“Why not?”

How to put this? “Well, horrible things happen when

I drink.” I tried to be specific and clear. I sounded like a

kindergarten teacher breaking down, step by step, how the

caterpillar turns into a butterfly. First, the caterpillar eats and eats

and eats. Then he spins a cocoon. A chrysalis is formed. Can you say

chrysalis, kids? Kevin, stop picking your nose. “I can’t help it. I will

drink, get drunk, go to a bar, get drunker, probably vomit, most

likely black out, and then you can pretty much guarantee I will

make out with a stranger. Kari will then break up with me, and

I’ll end up alone and drunk and in an alley somewhere. I really

don’t want that.” Man, that seems grim.

Maybe I am being too hard on myself. Maybe I am

being an alarmist. The sky may not be falling, Chicken Little.

I switched tactics and attempted to negotiate. “Do you think I

could drink just a little bit and it would be okay? You know, just

one drink? Is that possible? Like maybe things wouldn’t be as bad

as before?” There has got to be a way to make this work. I didn’t

know how, but maybe Patty would. Who would know better than

an alcoholic, someone versed on problem drinking who could

plainly see that I did not qualify? I got excited. Yes! This is it.

History doesn’t have to repeat itself.

Instead of telling me sure, go ahead, don’t see any reason

why not, you probably don’t have a problem, she pulled a book

out of her purse. Oh, brother. Here comes her pitch. Sister, I gave

at the office.

I refrained from rolling my eyes, assumed a serious

expression (furrowed brow, pursed lips) and leaned in,

manufacturing interest in what she was about to read. I mean,

she did come over and all.

Many who are alcoholics are not going to believe they are in

that class. By every form of self-deception and experimentation they

will try to prove themselves exceptions to the rule, therefore, nonalcoholic. Most of us believed if we remained sober for a long stretch,

we could thereafter drink normally. Commencing to drink after a

period of sobriety, we are in a short time as bad as ever. We have seen

the truth demonstrated again and again: “Once an alcoholic, always

an alcoholic.” We do not like to pronounce any individual as alcoholic,

but you can quickly diagnose yourself. Step over to the nearest barroom

and try some controlled drinking. Try to drink and stop abruptly. Try

it more than once. It will not take long for you to decide, if you are

honest with yourself about it.

Controlled drinking? What the hell is that? I can’t do that.

I knew I could not abruptly stop once I had started drinking. I

started to panic again. What does this mean? Wait. This can’t be

right. My mind fogged. I don’t want to be an alcoholic. I can’t be

an alcoholic. Shit. Stupid whiskey. Stupid book.

“Patty, I don’t want to be an alcoholic.” I don’t want that to

be me.

“Maybe you’re not. Go try to drink.” Wasn’t she listening?

Bad things happen when I drink.

“But I can’t. I can’t start drinking and stop. I can’t.” This isn’t

happening. I don’t want that book to apply to me. That book is

for alcoholics. I don’t want to be an alcoholic.

“Honey, why don’t you come with me to my Saturday

morning ladies’ meeting?” Her voice was kind, gentle. “There will

be people there you can talk to and maybe ask some questions.”

A meeting? How is that going to help? I can’t drink, and I

can’t not drink, and Patty wants me to go to a meeting? I am so

screwed.

“A meeting?” I tried to buy some time to think of an excuse

as to why I should not go with her. This was a bad idea, calling

her. I am not ready for this. “I…”

“Why don’t I pick you up at 9:30?” Boy, she is good. Crafty.

I did not want to go to a 12-step meeting. Not at all

interested in communing with strangers about drinking. La la

la, touchy feely. Talk about lame. Man. I was stuck. Can’t drink

without losing my underwear, can’t not drink without help. I

agreed to go with her. Shit.

How to Make a Soup Sandwich

(a list of things I love about Iraq)

Daniel Otto

The smell of camel dung, trash burning, diesel and oil.

Cordite and sulfur that burns your nostrils

From inky, blue clouds that quickly pass away.

The wails and cries on a lousy megaphone

Calling the faithful to prayer

While I wash my hands with dirty water.

Blood spilled on fine, marble tiles, the smell of iodine.

A mother with no face, moans for a baby

She hears crying but cannot see,

Will never again see.

The rhythmic beating of rotor blades,

Metal steeds with heaven or hell on board.

The hollow sound of mortar tubes, tha-thump.

The silence and fear that follows, waiting.

The smell of curry in the market,

Food you’ll regret eating and tea that’s too sweet.

Haggling with a child over pirated French smut

For greenbacks to feed his family.

Crowded, pockmarked highways.

The Fiats and BMW’s, and my sights

Leveled on their windshields.

My child’s laughter a world away,

Her first steps unseen.

Explosions and death.

Men at their worst and men at their finest.

The bagpipes.

A roll-call ending in silence.

Mourning, my brothers and sisters

And knowing we will never be better

Than at this moment,

And tears when I hear the bagpipes play

A dirge for the warrior caste.

Sun in the Sandhills

Tara Novak

It was in August of 1987, in the oppressive heat of the

Western Nebraska sun, that I fell in love for the first time. It was

love complete and blinding, and it knocked me off my feet. Only

thing is, I was just seven. Years later, I remembered the incident

and had the vocabulary and context to understand what had

happened. But then, in the shimmering heat waves of the late

summer days, I only knew that the stories that filled my girlish

imagination had suddenly, inexplicably, come alive for me.

Other kids went to Disney Land or to Boston or Miami or

even Paris for vacation. My family went for one week to Chadron

State Park. All five of us sisters and my parents piled into our

1985 silver Toyota van—arms and backpacks loaded with

books and dolls, blank paper, crayons and decks of cards for the

journey—and away we went. Eight hours and many renditions

of “Home on the Range,” “My Favorite Things,” and “White

Christmas” later, we arrived at our little cabin in the woods.

The world is crisscrossed with mountains—purple, majestic

and remote. There are oceans, deep and cold and bracing. Cities

zoom and zip with excitement, vigor and bright lights. Western

Nebraska has none of these glamorous beauties to offer. Still,

there is no place like Chadron. The wind there whistles through

the tops of the white pines, a continuous mad organist playing

for no one. The scent of the tall conifer trees mixes with the

heady aroma of sweetgrass, with the dry taste of dust kicked up

by the hooves of horses and herds of cattle, with the salty earth

of the sandhills and the loam and granite and cool lichen of the

bluffs. It is the smell of vast potential. It is the smell of thousands

of years of human history, undocumented and unrecorded. It is

the smell of life.

That first night at Chadron, I stood with my family on the

top of Lookout Point. In my towheaded pigtails, clasping tightly

my brown bear Honey, I stood on the edge of the cliff, breathing

in the sharply carbonized air from the lightning storm crackling

haphazardly across the horizon. From that precipice, the entire

world made sense.

Eager to explore my new surroundings, the next morning I

threw on my sneakers and hollered to my mother as I bolted out

the door, “Mom! I’m going down to the Trading Post. Be back

for lunch!”

My sisters followed my madcap dash through the

underbrush and overgrown trails to the main road. I didn’t

know the route, but had very seriously studied a map in the

car the day before and was certain I would find the way. My

diligence paid off: there was the Trading Post ahead of me. I

knew from reading about Chadron State Park before leaving

Omaha that the Trading Post was the center of all State Park

activities—informational movies about the area, jeep and horse

rides through the bluffs, ceramics, games of archery, horseshoes,

dominoes. I raced into the building, slowing momentarily to ask

a bottle-blonde college-aged girl behind a counter if there was

anyone working.

“Yeah,” she answered chomping her gum, “Out the side

door and in the field…”

I tore out of the building and stopped. There he was. My

Mountain Man. I had never seen anyone or anything like him.

My little pioneer heart beat faster in its cage. He was tall and

wearing handmade animal skin clothing. He had dark, slightly

wavy hair and a heavy, full beard. I crossed the browned prairie

grass and approached him. He looked down from his height into

my painfully sincere eyes. I needed more than anything for this

man to be genuine.

“Well, hello. I’m tanning this buffalo hide. Would you like

me to show you how?”

That began one of the most magical weeks of my life. My

Buffalo Bill told me how he had hunted and killed the buffalo

with an arrow, which he had made himself. He taught me about

Native American respect for animals, about the idea that the

animal had sacrificed its life for the survival of its hunter, and,

because of that, the importance of using every part. Together, we

scraped out the hide with the bones; I held the wet, coagulated

gray mass of bison brains in my hands as he used them to tan

the skin. Later that morning, my mother and father arrived, and

Bill showed us how to start a fire using nothing but charred cloth

and flint. Over the week, he spent hours with my sisters and me,

patiently explaining how to straighten feathers on arrows, how to

set up and live in a tipi through the harsh Nebraska winters, how

to blaze trails and shoe horses and build proper fires. One night,

when it was pouring rain, Buffalo Bill and two other State Park

employees sat with my family at the Trading Post, laughing and

playing dominoes until long past my bedtime.

Of course, there were moments spent beyond the Trading

Post that first August in Chadron. I visited the corrals and fed

the horses each day. I bravely tromped off on my own, pretending

to discover the land and invent trails. My sisters and I found a

family of turtles in the little pond, adopted them for the week,

and were righteously shocked when my mother wouldn’t let us

haul them in the van the whole way back to Omaha.

When my family returned to Chadron the next year,

Buffalo Bill was gone. That summer the forest fires ravaged all of

Yellowstone and Glacier National Parks, and he had gone off to

fight the fires. Another man was working in his place. I still went

to the Trading Post to learn about the Wild West I loved, but the

deep thrill was gone.

I have since wondered where Buffalo Bill eventually

wandered after the fires. Two years ago, my parents and sisters

decided it would be a brilliant idea to go on an all-family trip

to Chadron again. This time, with two vans, two parents, five

sisters, three husbands, a niece, a nephew, a guitar, and a violin, it

much more resembled a parade or a circus than a vacation. In one

stolen moment of silence, my Dad and I went jogging together

in the velvet dusk and pine-sweet air. As we passed the Trading

Post, I hesitantly brought up the subject to my father…

“Um…Dad…do you remember a guy…he worked at the

trading post our first summer here?”

He remembered. How could he have forgotten? We

reminisced warmly of that week in 1987. Apparently I was

not the only person who had found Buffalo Bill’s courage and

dedication to his lifestyle appealing and refreshing.

When I talked about how much this Mountain Man had

influenced my young imagination and thoughts on life and the

environment, how he had made history come alive for me, my

Dad—uncharacteristically—opened up and told a story I had

never heard. He talked of a traveling musician passing through

the Boy’s Home where he lived as a child. When the road-weary

man strummed the first chord on his beat-up acoustic guitar, my

Dad’s world shifted. He knew in that instant that he had to be a

guitarist.

Love is a funny thing. Buffalo Bill probably never had

any idea how much one little blonde girl adored and idealized

him. It doesn’t really matter. He offered something passionate

and tangible—and glitteringly alive—in direct contrast to the

quiet death of my suburban childhood. His existence was exotic,

completely off the grid, irrational by all modern standards. There

was a romance to it all that resonated through and through my

being, and still does to this day.

I only wish I knew his real name.

Colorism

Nicole Upchurch

I was kid when I came back to black

From livin’ across the pond to St. Louis.

I did a stint in DC for a couple a months.

That wasn’t black yet.

Had no idea

What my real world was back then.

Had all kinds of friends

Black, Puerto Rican, White, Hawaiian.

Couldn’t jump double dutch

Didn’t know Rockin’ Robin

“You talk like a white girl.”

Where I had been

Being dark skinned wasn’t a bad thing.

Gapped teeth made me different.

When I came back to black

I was ugly.

They called me an Oreo,

Black on the outside,

White on the inside.

They didn’t want me as a friend.

Said “she thank she better than us.”

The white girls took me in

Never made me feel bad.

I was just a nice kid to them.

I tried comin’ back to black,

But they wouldn’t let me in

And to think these are the people I call ‘us’.

Tolerance and Community

Angel Dewaele

I don’t care what they do behind closed doors, but why

do they insist on flaunting it? I mean, it’s on television, in the

movies, out in public. Why can’t they just be who they are and

keep it quiet? I decided to find out what makes these people tick.

What’s it like to be pitching (or catching) for that team? I know

one personally, so I decided to ask.

Mark met me in a bar downtown. He looked around,

nervously scanning the room. He was out of his element. He

looked normal enough, though, even kinda hunky. He’s a

firefighter, and you know how everyone feels about those guys.

He could probably pass. I was worried that people might think

I was one since I was with him, but it’s not like you could really

tell just by looking. I chose a table near the entrance, or exit, I

suppose, in case this didn’t go so well and either of us had to

make a quick getaway.

Men and women enjoying after-work camaraderie laughed

around us, tables filled with appetizer and drink specials. I had

so many questions. When did he first realize it? Is it a phase?

Do his parents know? Although it was happy hour, Mark didn’t

seem happy at all. His jaw was set. He sat with his back straight

and kept looking over his shoulder. I offered to buy him a drink,

maybe take the edge off. What do they like to drink, anyway?

This wasn’t going to get any easier as we sat there, so I decided to

dive right in. “Mark, just how did you become a heterosexual?”

He looked at me sideways, not knowing what to make of

such a question, and answered that he has always been that way.

“What kind of answer is that? Are you straight because you have

a fear of others of the same sex? Maybe you just haven’t found

the right guy yet.” Mark twisted his face in disgust. Was it the

suggestion of having a same sex partner or the fact that I would

actually ask him to explain his sexuality?

I continued. “Just what do men and women do in bed

together? I mean, how can they truly know how to please each

other, being so anatomically different? And why do heterosexuals

feel compelled to seduce others into their lifestyle?” Mark rolled

his eyes, not amused. He has a daughter in pre-school, so I

thought it appropriate to ask if he considered it safe to expose his

kids to heterosexual teachers considering the disproportionate

majority of child molesters are straight (Yetman). Oddly, he

didn’t think it unsafe at all. That’s a shame. He really should

be more on top of that sort of thing. While we are at it, what

about all those “special” rights heterosexuals have, like the right

to get married, the right to adopt children, the right to spousal

benefits, the right to visit partners in the hospital, rights of

survivorship, the right to protection from discrimination in work

environments, housing, and public institutions? I mean really.

Who do they think they are? All this based on who they sleep

with?

Okay, okay, you get the point. Mark and I have been friends

for a couple of years, and he knows I’m gay. What he doesn’t

know, though, is that I get asked these same questions, in earnest,

by the straight community without hesitation or a sense of

impropriety. He was even amused having these questions posed

to him. And while the questions may seem silly to him, as they

should, they hurt and anger me. These questions speak volumes

about the division we have in our community. I can’t feel part of a

community that seeks a reason for, not an understanding of, who

I am. The implication is that if there is a reason, maybe there is a

cure.

Mark doesn’t experience this. He is a middle-class, straight,

white male. He belongs to his community as a neighbor, a

worker, a father, and a husband. No one would ask him to justify

his life or try to “cure” him. I work; I own a house. I have had

a partner the same length of time that Mark has had a wife.

I live in the same city as Mark, but I am denied the benefits

of community, from getting married and sharing insurance

to holding hands at the zoo without fear for our safety. Mark

cannot understand this and tends to minimize and deny my

experience. He has no point of reference. He is able to walk into

the grocery store, the video store, the bank, holding hands with

his wife, and no one blinks an eye. I can’t imagine what it must

be like to have that level of assimilation. When I hold hands

with my partner, it is always with the awareness that we could get

attacked. If we only receive stares and snickers, we are relieved—

relieved that we weren’t brutalized, that we were tolerated. But,

to have community, tolerance is not acceptable. The paradox of

practicing “tolerance” is that instead of resolving problems that

stem from difference, it actually perpetuates intolerance and

inequality.

We tolerate things that are unpleasant: the heat, a

boring lecture, a headache. These are things we would rather

do without, but are unavoidable. According to the United

Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization,

or UNESCO, tolerance means that we are “living together

with respect, acceptance and appreciation of the rich diversity

of our world’s cultures, our forms of expression and ways of

being human. Tolerance is harmony in difference” (“What is

Tolerance?”). I applaud the spirit of this message; however, there

is a problem. The word “tolerate” implies an ability to punish

and a conscious decision not to. Since the group in power (in

this case, the heterosexual community) is encouraged to practice

tolerance, they then have the power to not tolerate. It’s as though

they have their hands around our necks and are choosing not to

squeeze. We are always aware of the hands, able to crush. We are

at their mercy, therefore, unequal. We are tolerated because we are

different, and we are unequal because we are tolerated. Without

equality, we cannot have community, but we need differences for

our communities to thrive.

Not everyone in a community needs to be the same.

Equality is not about homogenization. We can have difference

in our communities and not have discrimination. Difference can

be productive, as long as those differences are equally regarded.

A baker is different from a mechanic, yet both are viable

members of the community. We don’t judge one as less than the

other. We are dependent upon their respective contributions to

the community; a community of all mechanics would not be

sustainable. A community is interdependent. If we stop only at

tolerance of our neighbors, the scales remain unbalanced and we

are not maximizing the potential for a strong community. We are

actually increasing the potential for discord. If a group is denied

their rights, they will fight for them. It is in our best interest to

embrace those different from ourselves, if not for humanitarian

reasons, then only for a little peace and quiet.

Since tolerance is contingent upon separation, the

alternative to tolerance is engagement. Respect, not tolerance,

should be taught in order to close the chasm that divides us. We

need to radically accept that our way is not The Only Way and

actively approach those who are different from us. Education

and experience will lead to equality. With equality, we can have

community.

In order to obtain partnership in my community, I will

continue to challenge the Marks of the world and remain open

about my sexuality until it is no longer an issue. I will continue

to educate others. I will demand inclusion and respect until I

am able to enjoy the same benefits straight people get for paying

the same taxes and living in this country. But the onus does not

rest solely on me. It is imperative that those whose “lifestyles” are

different from mine also embrace these principles until gays are

no longer the shadow members of community.

Works Cited

“About Us: What is Tolerance?” Tolerance.org: Fight Hate and

Promote Tolerance. 2005. Southern Poverty Law Center.

1 May 2007 <http://www.tolerance.org/about/

tolerance.html>.

Yetman, L. “Answers to Politically Incorrect Questions.”

The Heterosexism Enquirer. January 2006. Memorial

University of Newfoundland. 1 May 2007

<http://www.mun.ca/the>.

Poor Relations

Zedeka Poindexter

Today is the funeral for one of the Strong daughters.

Years ago one moved south and labored though packing houses

and inner cities.

The other stayed near family and provided her children every luxury.

Like the last funeral we

Embrace delicately

Cry silently

Separate from habit.

Maybe it takes being the poor relation to notice this.

We are the folks who put water in the ketchup bottle

Know exactly how many miles are left after the fuel gauge hits

empty

And have been close enough to shit to recognize the look people

toss its direction

In the land of the city cousins

The rules of politeness just don’t work the same.

This sister we bury today died at home

Blood sugar out of control

Gangrene in the wound her well-bred babies could not bring

themselves to dress

And we are the poor relations

Who grieve silently enough not to embarrass the city folks

Then leave before the battle royal over property, possessions and

insurance money.

We may be broke as the Ten Commandments

But down here in the sticks

We survive through each other.

When one of us is paid

We all eat.

When one of us is sick

Everyone prays.

When a child is born

We are all there to show them how to carry this tradition on

And when the sister who had nothing but Medicaid and a

mortgage died

It was also at home

With my hand in hers

Telling her whatever world she chose to surrender to

We would say her name with a smile on our lips

Even as the family came through to tell us where she went wrong

And look uncomfortably at the too small house she fought to

keep.

The smell of us that causes you to lift your noses at family

gatherings is the thickness of this family

What keeps us together when your cultured values evaporate in

the face of trouble

You smell the sweat of women who work like men in their

absence

The rot of dying because we care for our sick

The joy of knowing we clean up good, but by hook or crook this

family will make it

My grandmother taught me that

Which one of our family lines are lowly

Something has got ya’ll confused

Believing hair care commercials and prime time sitcoms

Lost hold of the knowledge

Fat meat is greasy

Broccoli ain’t greens

And family is for more than the free shit when our elders die.

Why is it only the bumpkins know this?

Us poor relations

Small town

Limited education

Pitied

Wrap your clucking tongue around this.

We came from the same people

We aren’t poor and perfect

We know weed spots and holding cells

You are not corrupt and cold

Some of you believe in work and family

But there is this status-shaped chasm between us

That only seems to widen every time we gather to pay respect

To the dead but never to each other

Making the poorest relations of all

The two generations of children raised across an abyss of class

and accusations

Who don’t know what their family looks like

And have no feeling of solidarity beyond the knowledge we

should all be grieving right now.

These women we buried were sisters

Blood and back up whenever needed

Never separated by more than a phone call

But we . . . don’t have each others’ numbers

Don’t call or know each others’ names

Just look at each other across caskets

Remembering the virtues of the family we lost

Forgetting we were all taught better than this.

The Artist

Brooks Utterback

New Mexico had been a state for only fourteen years when

my father was born. The 47th territory to join the Union, it was

acquired from Mexico in 1912 after centuries of invasions from

conquistadors and Native Americans. My father has the blood

from all of these warriors. He was born in the mountains near

the Rio Grande River in Magdelana, a cold and dusty town.

A miner’s town, it was a place where a man understood the

meaning of hard work. Magdalena today is a barren, untouched

land with only tumbleweeds and scrub for nature’s landscape,

unchanged from centuries past.

This is where my father grew up, along with three brothers

and two sisters. My father never knew his birthmother; her

life ended five days after his began, consumed by infection and

fever. At the age of eighteen, my father left, joined the Merchant

Marines, and never looked back. He traveled the world, all the

while working as a cook on supply ships.

He later settled in San Francisco and began training as an

artist and sign painter. He loved the advertising of the 1940’s. The

flashing neon signs that beckoned drinkers to bars and diners to

cafes drew him in. He learned the art well: calligraphy, Gothic,

Old English—all letter styles he could replicate. Enamel paints,

camel hair brushes, and turpentine, these tools of the trade filled

the garage where I grew up. This combination of odors always

takes me back to my father’s garage.

He worked alone in the cool, dark shop. After school,

my hours were spent sitting on an overturned milk crate,

handing him solvent soaked rags or charcoal, and I was always

mesmerized by his steady hand. Believe it or not, that garage

allowed me into some of the finest shops in the city. Beauty

parlors, butcher shops and fine restaurants in San Francisco

ordered signs from my dad. Sometimes he let me ride when he

delivered and installed his works of commercial art. I met shop

owners and chefs. Barkeeps let me sit at their bars and drink

ice-cold 7UP, an exotic maraschino cherry added for my delight.

A pair of white, patent leather shoes became mine courtesy of

the Golden Goose Shoe Store. Hard candies and Snickers bars

were tucked into my pockets. Once, a live rabbit came home as a

family pet. I don’t know if dad paid for these goods or they were

gifts bestowed to a little girl, but I always felt special spending

time waiting for my father while he hung his custom-made signs.

Six days a week for thirty years, my father worked in the

garage honing his skills. Not satisfied with only painting plywood

or paper signs, he took on jobs lettering vans and boats. Delivery

trucks would be colorfully painted with whatever the business

specialized in. Pre-computer age, it was my job to research his

subject out of books and magazines. A seafood delivery van

required me to find an old copy of Field and Stream. Freshwater

or deep sea, colorful flying fish came to life on a panel truck

because of my father’s trained eye.

Sunday was his day off. Sleeping late, my sister and I often

made brunch for my mom and dad. We talked and laughed and

caught up on the past week’s events. In the afternoon, he read

books on chemistry or history, never novels or magazines. His

thirst for knowledge was insatiable, and to this day, he spends

hours learning about great artists or inventors.

At the age of sixty-two, my father retired from the sign

business. He took up woodcarving, and for extra money, used

his old work van as a moving van. He advertised and set his

price. If a job came and he needed extra help, again I was his

assistant. We hauled for every ethnic group in the city. Everyone

befriended him. His Indian red skin and thick black hair

allowed him to look Mexican, Vietnamese, or Southeast Asian.

Sometimes people didn’t have enough cash to pay him in full,

so they would give him a television or lamp for payment. He

said it made them feel good to help out an old man. I cleaned

the empty apartment and hauled their trash. They would feed us

tacos or sandwiches, whatever the family was dining on. With

my father, it always seemed more like a moving day party than a

dirty work day.

My father is now eighty years old. He works in his garage

every day, his shop still filled with paints and art supplies.

Primitive carved wooden busts of his family and friends line the

driveway, our names engraved into the front since our identities

are too vague. His creations are made from discarded wood or

metal. Hand-made lighthouses fabricated of brightly painted

scrap metal beckon passers-by to stop and look. His daily threemile walks are like treasure hunts when he discovers unwanted junk inside a construction dumpster.

His whimsical public displays continue to attract urban

artists to his shop. Drawn in by the color and movement of his

creations, they soon discover this charismatic man holds many

secrets to life.

Stone Critics

Hoken Aldrich

They stand on the floor like stone critics

Shifting eyes, anticipation building inside

We look over each spectator, each one

Stares back, waiting for us to make our move

And there’s our cue, the stage lights up

Music turns on, our first notes strike

The statues like a sledgehammer of sound

Forcing them to move in one direction or another

We arrange and rearrange this crowd like pieces on a chessboard

Strategically setting each rhythm and rhyme

Let them knock each other over, watch the crumble.

We won’t stop until checkmate.

The Battle of River Run

Catherine Burghart

The front seat in a vehicle has long been the choice of

those with discerning tastes. It is a throne of luxury nestled high

above the economy class. The cushion on the reclining chair with

built-in lumbar support is always a bit more plush, the legroom

more plentiful, and the cinematic window more than ample to

take in the beauty of the landscape rushing by. All the amenities

are at your finger tips: access to the personal butler that is the

cup holder, climate control at the touch of a button, and, of

course most importantly, complete dominion over the radio. It

is no wonder that wars were fought amongst my siblings and

me over this illustrious status symbol. The Battle of River Run

in the summer of 1992 was one such engagement that ended in

bloodshed and is forever etched in my memory.

The old farm house we lived in at the time had no air

conditioning, and unfortunately that year’s heat index was one for

the record books. Most of our days were spent in sticky clothes

anxiously awaiting Mom’s return home from work because we

knew that accompanying her would be our salvation. Every

evening she would pack us up and take us to be cleansed of the

devilish heat in the baptism of the cool swimming hole. On that

particular day, it was just my sister Mary and I waiting on the

front porch with our ears perked for the sound of gravel being

ground by tires. We were already in our swimsuits with towels in

hand when were heard that familiar sound and saw a trail of dust

left in the wake of Mom’s van plowing up the drive.

Mom’s “new” van was not so new. It was probably from the

late seventies, drenched in shag carpeting from floor to ceiling

with a bench seat in the back that folded into a bed. The wheel

wells were rusted out, the passenger side door would not close,

and the upholstery was dilapidated, but Mom must have thought

it was a great deal and tried to fix it up. She bought some Bondo

to fill in the holes, rigged a bungee cord to secure the wayward

door, and painted the whole thing with some teal swimming pool

paint she had picked up at a yard sale. It was a piece of crap, but

what did I care? All I knew was that it had a front seat and that I

wanted to be perched there. Unfortunately for me, Mary had her

eyes on the same prize, and before I could purse my lips to utter

the syllables, she hastily yelled, “Shotgun!”

There are many ways to decide who gets the front seat

during a trip in an automobile. Some people use Rock, Paper

Scissors; others take turns, but my siblings and I had elected to

use “The Shotgun Method.” The rules to this competitive game

are quite simple. The first person who shouts “shotgun” before a

trip and with the vehicle in sight stakes claim to the first class

accommodations for that ride. So, in keeping with the rule, I

accepted defeat and crawled into the back.

Sitting there, watching my sister indulge in the

complimentary vintage Merlot while I was back in coach with

mere peanuts, made me realize that this was simply unacceptable,

and like Pinky, I began to hatch a plan. To my advantage, I knew

my mother’s route. Without fail, she would pull off at the small

country store along the way and let us pick out something laden

with sugar to subdue our shakes while she grabbed something

laden with liquor to subdue hers. This would be my golden

opportunity because according to the bylaws of Shotgun, as soon

as the front seat is vacated, the game starts again, and the throne

is up for grabs.

When we got to the store, I wasted no time. I dashed for

the freezer, grabbed an ice cream cone, and raced for the exit.

Halfway through the door, I turned and in a clear voice shouted,

“Shotgun!” However, this did not go over as planned. A heated

debate ensued over the validity of applying the move-your-meat,

lose-your-seat clause to this instance. Mary made the case that it

had only been three miles to the store and that this was hardly a

full trip. I stuck to my position that a strict fundamentalist stance

needed to be taken in regard to the interpretation of the law, and

Mom did not care either way. She had had a long day at work,

and this was not how she wanted to spend her evening.

“That is enough! This is ridiculous!” she shrieked in the

same tone that any mother adopts when she is about to use her

child’s full name: “Catherine Claire, you scoot over and share that

seat with your sister!”

“But Mom,” I complained with a furrowing brow, “I called

it!”

“No you didn’t!” Mary retorted. “There was nothing to call!

It’s my seat!”

“I have had it with you two!” Mom said, her eyes now

wide and her finger stiffly shaking. “We could have had a lovely

evening, but like always you kids have to start bickering over

trivial things! We are going home!”

“But Mom,” Mary and I grumbled almost in unison as if we

were suddenly deciding to join forces to defeat a common enemy,

“We want to go swimming!”

But there were no “buts” about it. Mom had made up

her mind, and as soon as we realized that she was not going to

budge, we disbanded and became adversaries once again. Now

the motivation to fight, however, had changed. It was no longer

territorial, but vengeful. The evil-eyed expression mirrored on our

faces crystallized our position on the matter—‘It is all your fault!’

Mary was the first to retaliate. She climbed in and with a

bump of her hip forced me to share the throne. With that, she

set the rules for engagement and changed the seat cushion into

a tangible expression of who was guilty. The entire way home,

elbows were bruising ribs as we fought for a victory that could be

measured in inches of foam and faded upholstery. As we turned

into the driveway, I knew that I was losing ground. So in a last

ditch effort to project the shadow of blame onto Mary, I shoved

her hard into the faulty passenger side door, and she disappeared

from sight.

“Stop the car!” I immediately screamed. “Mary fell out!”

But before Mom could bring the tires to a standstill, I

had my feet on the ground. A thick cloud of dust suffocated

my vision, but I could hear her crying, and when she came into

sight, I could see why. A long gash extended from right above

her elbow to halfway down her forearm, and I could see the bone.

Victory was anything but sweet! The ridiculousness of the battle

was evident in my ice cream cone’s melting and merging with the

dust on our driveway to become nothing more than mud as we

waited for the ambulance.

Dead or Alive

by Jason L. Jablonski

“Dude, where’s the hammer?” my brother asked me with a shit-eating grin on his face. I didn’t want to tell him, “It’s hanging back there on the workbench!” We were practically yelling at each other over the heavy rain and thunder being poured into the fully opened garage door. “You sure you wanna do this?” he asked. Hell no, I didn’t want to do ‘this’. I didn’t even know what ‘this’ was. Hesitantly, I sputtered, “I gotta learn sooner or later!”

* * * *

All day long we had been fishing the Salt Creek for catfish. We started well before noon, and now the sun had been down for a solid four hours. In the middle of summer, that would make the time about two in the morning. We were brothers and loved spending time together fishing and telling stories. But the one story I regretted telling him was how I had never learned to clean a fish. And that I had always found a way to have the other guy do it instead of myself. I was slightly proud of that fact, but never thought that this little bit of information could come back and bite me in the ass.

On the way home from the river he started in on me. “So, who’s gonna gut all these cats for fryin’? I know you’re wife ain’t gonna do it. And I must have pulled something in my hand, so I can’t do it.” I knew what he was getting at. I’ve known the kid my whole life and could spot his sarcasm a mile away. “Alright Tony,” I said swallowing my older brother pride, “Will you show me how to gut a fish?” He just smiled. Smiling in his sinister way, he was loving it, “Of course I’ll show you how. You’re my brother. I love you.” I was shaking my head thinking, ‘This ought to be lovely.’

By the time we pulled up to the house, there were no signs of the rain letting up that had started soaking us before we made it to the truck from the riverbank. Comfortable in our own filth, we silently sat there in the driveway contemplating our next move, mainly because we had said enough over the past 15 hours in one another’s company. I broke the peacefulness with, “So, do we gut ’em alive or do we have to kill ’em first?” He answered with, “I don’t know, how would you rather do it? With ’em dead or alive?” I thought about it for a minute. Being somewhat of a sensitive individual, I figured the cleaning wouldn’t be as mean or cruel if it were already dead. The fish wouldn’t feel the filet knife slicing through its cheek side, all the way down to its tail, knocking against its spine, vertebrae after vertebrae. Its violent convulsions could be avoided from slicing open its belly, extracting every little piece of undesirable fish part I didn’t want. I myself did not want to put one of God’s living creatures through this horrific spectacle of being gutted alive. Confidently I answered, “Dead.” Then my own brother retorted with a quick, “Okay,” to seal the deal.

Knowing what we had to do from having done it a hundred times before, we both jolted out of the truck in a frenzy, impossibly trying to avoid getting less soaked than we already were. I grabbed the cooler full of catfish. He grabbed everything else he could carry from the bed of the truck that we didn’t want sitting outside all night in the rain. Out of breath, we both stood there in the open garage with our hands on our hips and smiles that said, “Job well done, brother.”

Smiles or not, we were hungry and hadn’t eaten in some time. We always tended to eat all of our food too early in the day. Bragging to each other about how we were going to take catfish home and fry up filets did not help. That kind of talk just made us want to eat. If we didn’t consume meat soon we were going to get really cranky. We were home. The truck was parked and locked up. The gear was dried, drained, or put away. It was time to get down to brass tacks. My brother made sure of that. And I could tell he didn’t want to wait any longer.

* * * *

“Dude, where’s the hammer?” my brother asked me with a shit-eating grin on his face. I didn’t want to tell him, “It’s hanging back there on the workbench!” He grabbed it and handed it to me as if it were the Olympic torch. “Well, let’s get to it! Hit it square on the head and kill it!” At this point, if I had a tail it would have been tucked deep between my legs. This did not seem right. “Are you serious?” I asked. With no hesitation he replied, “Yep, hurry up. Let’s go. We still gotta cook the sons of bitches!”

With that lovely piece of encouragement, I got into position. Going down on one knee, I raised the 28 oz. framing hammer up above my head and squeezed the catfish as hard as I could around its belly. It must have been at least a 10-pound cat and strong to boot. Its tail was kicking back and forth, jerking the rest of its body, having no idea of what was going on and still fighting for its life. My heart was racing. The rain was bouncing off of the pavement, lightly misting us both. Tony had suggested earlier we get close to the outside, as to avoid too many blood stains on the garage floor. Time had frozen. Out of the corner of my eye, I could see Tony laughing, but could not hear him. Every single one of my senses were laser focused on one thing: killing a catfish with a hammer.

I hesitated lowering the hammer. “There’s no way it’s done like this! Screw this, man! I ain’t doin’ it!”

“Let’s go, Sally, I’m hungry!” he demanded.

Alright! Fine! Whether he was messing with me or not, I was going to take my medicine and not let him know it bothered me anymore. My little brother was calling me out. So what? I had never done this before. Gutting a fish was one he had up on me. But killing did not feel at all natural. Just to save my pride, I had to do it. With every fiber of my being I lifted that hammer again above my head. My other hand was now numb from not letting up on the death grip I’d held for so long on the fish’s belly. Back in position, he started to coach me, “Make sure you hit it square on the head, right behind the eyes!” I tried one practice swing, “And do it hard!” He kept yelling. I was envisioning its head splattering all over us and the garage like a tomato. I let out one last breath.

WOMP! TINK! Dead on, but no splatter. The hammer had bounced off of it’s head and onto the cement, not killing it. “Do it again!” Tony belted laughing hysterically, “Harder! You swing like a girl!” At this point I had dropped both the hammer and the fish. My body was shaking from an ice cold chill crawling up and down my spine. I felt sick to my stomach. “So much for taking my medicine,” I thought.

A couple of minutes had passed, and I had regrouped. I looked down at the writhing fish I had just pelted in the head and decided this was way more cruel than cleaning it alive. But the reality of it was that I had to finish what I had started. And I accepted that. In doing so, without warning, I quickly grabbed the hammer and fish. Swinging the tool around my side, I popped it with a WOMP! And then a smashing second, CRACK! This had definitely killed the cat. I turned to my brother and told him to show me how to do this while it was alive because the hammer in the head thing just wasn‘t going to work for me. My brother, dumbstruck by the sudden burst of energy I had displayed, respectfully replied, “Okay.”

The Historical Significance of Kanosha, Nebraska

by Patricia Sedlacek

While searching for information on local Indian tribes in the Plattsmouth library, I happened across a story written by an early settler. In this remembrance, she described how her family had crossed the Missouri River at the town of Kanosha. This piqued my interest immediately because almost every day on my way home I turn off Highway 75 onto Kenosha Road. I then stopped by the Cass County Historical Society and asked for any information on the town of Kanosha. An employee confirmed that there was at one time a town three miles south of the ghost town of Rock Bluff, but the library didn’t really have any information on it. On my way home that day driving down Highway 75, I checked my mileage between Rock Bluff Road and Kenosha Road: three miles, almost exactly. It was this first small discovery that sent me down the path to many more discoveries and mysteries regarding the forgotten riverboat town of Kanosha, Nebraska. After many weeks of research, I am convinced that the historical significance of Kanosha, Nebraska has been overlooked and should be outlined in a condensed documented form and preserved on the actual site.

Kanosha was located eight miles down river from Plattsmouth, and it was three miles down river from the town of Rock Bluff. Much has been written about the history of Rock Bluff, but very little attention has been paid to Kanosha. The town began as an Indian trading post before the area was opened for settlement in 1854. Businesses sprang up quickly, as many of the earliest pioneers of the newly opened Nebraska territory crossed the Missouri River at this point. The site was known as Kanosha, but it was not incorporated until January 22, 1856. The little frontier riverboat town seemed to flourish for approximately ten years. There were several stores, a post office, school, saloon, doctor, wagon and blacksmith shop, and many residences (Gilmore, “Ghost Towns in Cass County”). At some point in the mid 1860’s, it began to fade into obscurity. The property is now all privately owned by the Biel family.

I began my research by contacting the present owner Lavonn Biel. She suggested that I look at the George H. Gilmore Collection at the State of Nebraska Historical Society in Lincoln. Dr. Gilmore had researched the history of Kanosha for approximately eleven years. He believed that Kanosha was “One of the leading ferryboat transfer points on the Missouri River.” He also noted that many biographical sketches of early pioneers mention the fact that they entered Nebraska Territory at Kanosha” (Gilmore, notes re:Kanosha). His interest in this site was because his father was one of the first settlers in Kanosha in 1855.

Dr. Gilmore was born in 1866 in Cass County and graduated from Rush Medical College in 1895. He practiced medicine in Cass County for most of his life. He is credited, along with Dr. Sturm from Harvard, with the “Turtle Mound” find at Rock Bluffs and the “Walker Gilmore Buried Village” at the White farm east of Murray, Nebraska (Gilmore). Many of his writings are housed in the Archives of Archeology at the University of Nebraska in Lincoln. Dr. Gilmore founded the Cass County Historical Society in 1935, and his contributions to society, both through his medical practice and as an historian, are immense. He died in 1955 and is buried at Oak Hill Cemetery in Plattsmouth, Nebraska.

To begin to understand the historical importance of the Kanosha site, we must start in 1804 with Lewis and Clark’s expedition up the Missouri. There has been much speculation as to the exact location of the Lewis and Clark campsite on the night of July 20, 1804, in what would fifty years later become Cass County. According to their journals on the day of July 20, 1804, Lewis and Clark passed a creek which they refer to as “L’Eauqin Pleure,” or the “Water Which Cry’s.” This reference would be to what later became known as “Weeping Water Creek” (Moulton). They also note increasingly large sand bars. This was possibly because the confluence of the Missouri and Platt rivers was approximately eight to ten miles upriver. In their notes they also describe high points of land which are the river bluffs of southern Cass County, later mapped as the lower part of the Pennsylvanian Wabaunsee Group (Moulton).

Lewis and Clark note that their campsite of July 20th was approximately one quarter mile above Spring Creek, below a high bluff, on the left side of the river (Moulton). This would put their campsite approximately one half mile south of the Kanosha site and north of Rakes Creek, most probably between mile markers 578 and 579 at the base of the bluff known as Flag Pole Point on the Biel property (Wood). What Lewis and Clark noted as Spring Creek was later named Rakes Creek, and due to the rerouting of the Missouri River in this area by the Core of Engineers in the 1940’s, it now empties into the river farther south than it did in 1804 (Wood). There is a marker at Flag Pole Point noting the spot as a Lewis and Clark survey point. It is not hard to speculate that a member of the expedition climbed to this spot to see what lay ahead for the next day’s journey, as it is one of the highest points in Cass County. The fact that this spot has been marked as a Lewis and Clark survey point is in itself historically significant.

From the marker at Flag Pole Point, it is a short walk to the Kanosha Cemetery, which is also situated on the top of the bluff. In reading over Dr. Gilmore’s notes from 1937, ones sees that he was appalled at the condition of the cemetery and tried to gather funds and public support to preserve it, without much success.

The cemetery is approximately one quarter of an acre, surrounded by a hog wire fence that is falling down in many places, and it is covered by such thick brush in the summer as to be almost impenetrable. Many of the gravestones are either missing or buried under one hundred and fifty years of debris. According to Dr. Gilmore’s research, there are at least twenty-one gravesites that are some of the earliest pioneers in Nebraska Territory (Gilmore, notes re: burials at Kanosha Cemetery). The pioneers buried in the Kanosha Cemetery, each in their own way, made a significant contribution to the early history of Nebraska and the westward expansion of the United States. The courage they must have taken to move their families to the wild unsettled frontier should at the very least be honored by the preservation of their final resting place.

One of these early settlers was John McFarland Hagood. He settled in Kanosha, having come from Kentucky in October 1854. He married Mary Katherine Brown in 1855. She was the daughter of Mr. and Mrs. Gorman Brown, who are also buried in the Kanosha Cemetery (Gilmore, notes re: John Hagood). John Hagood, along with Bela White, formed the Kanosha Land Company in December 1856, with himself as President and White as secretary. They filed a plat map for the town in 1857, which shows 56 blocks with approximately 591 lots.

In the early organization of Cass County, Governor Cuming divided the county into two voting precincts, Martin’s in the northern part and Kanosha in the south. In the second general election held on November 6, 1855, John Hagood was elected to the territorial legislature for Cass County and was again elected to the tenth session in 1865. He also served as a representative in the house in the fifth state legislature (Gilmore, notes re: John Hagood).

John Hagood enlisted in Company A of the First Nebraska Volunteers in June 1861 as a private and, by May 1862, had been promoted to First Lieutenant (Gilmore, notes re: John Hagood). John McFarland Hagood was a pioneer, business man, blacksmith, ferryman, politician, and civil war veteran, who was laid to rest in a cemetery on a high bluff in his home town, but is now forgotten.

When John Hagood came from Kentucky to Kanosha, he brought with him an African American slave. His name was Sam, and he is also buried in the Kanosha Cemetery, along with most of the Hagood family (Gilmore, notes re: Interview with Peter Campbell). The fact that a slave or former slave, depending on his date of death, was buried in a small, all white cemetery, in the mid-1800’s, is very significant.

Another one of the first settlers in Kanosha was Dr. George Gilmore’s father, John Gilmore. He came to Kanosha in the spring of 1854 from Ohio, with his first wife Rachel and their two young sons. There was no ferry at this time, so in order to cross the river he built a raft and directed it to the opposite bank near the trading post (Gilmore, notes re: Ferry boat at Kanosha). In 1855 John Gilmore, along with John Hagood, and Thomas Thompson were granted the first permit to operate a ferry at Kanosha.

John Gilmore’s first wife died shortly after giving birth to a third son at Kanosha in September 1855. According to Dr. Gilmore’s records, Rachel Gilmore is the first recorded burial in the Kanosha Cemetery (Gilmore, notes re: Burials at Kanosha Cemetery). Rachel was a twenty-nine year old mother of three who followed her husband into the unknown, uncivilized frontier, and after a short time paid the ultimate price. Now she rests in an unmarked grave, in a forgotten cemetery, in a forgotten town. John Gilmore remarried in 1860 and moved his family to a farm located six miles west of the present day town of Murray, Nebraska (Gilmore).

One of the most interesting and mysterious characters in this early pioneer town was Bela White. In Dr. Gilmore’s notes and correspondence, he seems to become quite obsessed over his eleven-year period of research with finding out who Bela White was, where he came from, and what happened to him.

Bela White owned the trading post at Kanosha, and he could probably be considered the town’s first settler. As the little settlement grew, so did Mr. White’s trading post into a good-sized store. In 1856, he and John Hagood formed the Kanosha Land Company, and that same year he was given a commission as Notary Public by Governor Mark W. Izard at Omaha City, Nebraska Territory (Gilmore, notes re: Kanosha Land Company). He was also elected the first County Treasurer at the first county election held on April 10, 1855 (Andreas). White was the postmaster in Kanosha from 1855 until its discontinuation in 1868 (Gilmore, correspondence re: Kenosha post office).

Looking at these facts regarding Bela White, I believe it became quite obvious to Dr. Gilmore that Mr. White was no run of the mill river-rat trading post operator and that he must have been well educated, thus inciting Dr. Gilmore’s curiosity of the man’s origin. In a 1937 letter to a Mr. Sheer who used to help run the ferry at Kanosha, he asks for information on Bela White, such as where he came from, did he have any relatives in this country, when did he die? (Gilmore, Correspondence to Mr. Sheer). In doing this research, I too had become quite intrigued with the mystery of Bela White, and I have made some exciting discoveries regarding his history before he came to Kanosha. Early one morning I simply googled his name, and to my astonishment got a hit on the very first site. It was in the Edward and Orra White Hitchcock Collection at the Amherst College Archives.

Bela White was born in 1798 to a prominent Amherst, Massachusetts farming family. His sister was Orra White Hitchcock, considered one of the earliest female artists and illustrators in the United States. She and the other White children were educated at home with a private tutor, and then Orra was sent to boarding school. I can only assume that if the Whites sent a daughter away for higher education in the early 1800’s, they must have also done the same for their sons. Orra’s husband was Edward Hitchcock, a scientist, educator, and minister at Amherst College for almost forty years. He was a Professor in Chemistry, Natural History, Natural Theology and Geology, and served as President of the college from 1845 to 1854 (Amherst College Archives). Bela’s brother George was a doctor, in Hillsboro, Illinois.

Bela White married Julia Ann Stanton on February 1, 1832 (Condarcure). This is the only reference to a wife I could find, and there is no record of any children. Bela was seventy years old when the post office closed in 1868, and there seems to be no trace of him or information on him after that. His name appears on the 1855 Nebraska State Census, and on the 1860 Census, but not on the 1870 Census. He had outlived his parents, siblings, wife, and had no children. Peter Campbell described Mr. White in his interview with Dr. Gilmore in 1948 as being a short and heavy set man, with full cheeks, blue eyes and had very long hair that hung near his shoulders. Where did Bela White go at the age of seventy in 1868? I think there is a strong possibility that he, like Rachael Gilmore, and many others, lies in an unmarked and forgotten grave in the Kanosha Cemetery.

I started my preliminary investigation of burials at the Kanosha Cemetery at the Cass County Historical Society. The Society’s official record of gravesites in this cemetery is ten (see Table 1). This was compiled by a simple walk through and notation of existing headstones by Maurice Carmichael in 1995. According to Dr. Gilmore’s research and personal interviews, there are approximately twenty two gravesites (see Table 2). Considering the size of the cemetery and the length of time it was in use, I believe Dr. Gilmore’s count to be far more accurate.

CASS COUNTY HISTORICAL SOCIETY

OFFICIAL GRAVSITE RECORD KANOSHA

NAME BIRTH DEATH

Augustus Case none 12/3/1861

John Pulley 8/24/1803 4/8/1865

Frances Biel 9/26/1882 1/8/1885

Emily Brochus 1831 1896

Andy Exeline 2/7/1863 7/10/1891

John Hagood none none

Four stones/unknown

Table 1 (Carmichael)

- GEORGE GILMORE’S RECORD OF BURIALS ATKANOSHA

NAME BIRTH DEATH

John Hagood 8/5/1818 10/21/1885

Mary Katherine Hagood none 8/26/1888

Adresse Hagood 1/1/1861 2/11/1861

Fredrick Gorman Hagood 7/24/1867 5/8/1879

Oscar Hagood none 3/3/1889

William Sutton 6/14/1840 2/9/1911

Harriet Francis Sutton 8/2/1839 1/8/1909

Rachael Anderson Gilmore 1826 9/1855

Andy Exeline 1826 7/10/1911

Baby of William. Exeline none none

Augustus Case 1819 12/3/1864

John Pulley 8/24/1803 8/8/1865

Francis A Biel 9/26/1882 1/8/1885

Emily Brocrus 1831 1895

Gorman Brown none none

Eva Brown none none

Jennings none none

Sam none none

Gustena Brown O’Dell Nix none none

Baby of Glenn Campbell none none

Two Rorebeck children none none

Table 2 (Gilmore, notes re: Burials at Kanosha)

All of the people in this cemetery deserve to be remembered on paper, and their gravesites maintained. They were real people leading real lives in a new frontier. I believe that several were born over two hundred years ago, such as John Pulley, Gorman and Eva Brown, Mary Hagood, and Augustus Case, who was one of the incorporators of the first Agriculture Society in Nebraska in 1856 (Gilmore, notes re: First Agriculture Society).

In the 1930’s, Dr. Gilmore tried to raise funds for preservation of these pioneer cemeteries, and also tried without much success to heighten public awareness of the destruction of many of the sites. He noted that the Doom Family Cemetery located in Cass County at that time was being used as a hog pen, and he was concerned that the Kanosha Cemetery could be made into a pasture. (Gilmore, Correspondence to Mrs. Mabel Tuttle). At that time there were no laws to protect pioneer cemeteries. It has only been in the last few years that the State of Nebraska has written statutes pertaining to abandoned and neglected pioneer cemeteries.

According to Section 12-805 of the State of Nebraska Statutes, the county board can expend money from its general fund for care and maintenance of these cemeteries, which can include repair or building of fences and spraying to control weeds (State of Ne. Statues Sec.12-805). This would be a great beginning to the preservation of the Kanosha Cemetery, and the owner of the property would not have to incur the cost herself.

Section 12-807 states that when petitioned by thirty-five adult residents of the county, the county board shall expend money to preserve and provide maintenance for an abandoned and neglected pioneer cemetery (State of Ne. Statues Sec. 12-807). As I have talked with various people in my community regarding my interest in preserving this cemetery, I have discovered that there are others who are as interested as me in trying to get this site cared for. I don’t think it would be very hard to get thirty-five signatures.

The first step of course would be to meet the criteria of an abandoned and neglected pioneer cemetery as defined by Section 12-808. The cemetery must have been founded prior to January 1, 1900. The first recorded burial in Kanosha was 1855, and the last was 1911. The site must also contain the graves of persons who are homesteaders, pioneers, first generation Nebraskans, or Civil War veterans. It can be easily proven that most of the people in this cemetery are pioneers and first generation Nebraskans. Also, it is on record that John Hagood was a Civil War veteran. The last requirement is that the cemetery has been generally abandoned and neglected for a period of at least twenty years (State of Ne. Statue Sec. 12-808). Since the last burial at Kanosha took place nearly one hundred years ago, and due to its impenetrable condition today, I would assume it would meet this requirement easily.

Section 12-810 says that any county affected by sections 12-807 to 12-810 shall provide for one mowing per year, and after five years of maintenance, a historical marker giving the date of the establishment of the cemetery and a short history shall be placed at the site of such cemetery (State of Ne. Statute Sec. 12-810). Spraying for weeds a couple of times a year, mowing once a year, and placing a marker for this historical little cemetery does not seem like it would put much of a burden on county funds, especially when compared to the loss of so much Cass County and Nebraska history if the cemetery were not preserved.

The history of the Kanosha site goes back farther than the town itself, or its little cemetery, to a band of brave, courageous, adventurers who set out to map the mighty Missouri River all the way to its head waters and beyond to the Pacific Ocean. Lewis and Clark’s exploration was the beginning of the western expansion of the United States, and the town of Kanosha and its early settlers played an important part in that continuing expansion.

There isn’t much left of the once booming riverboat town of Kanosha, Nebraska, other than one crumbling old building, several deteriorating foundations, and an overgrown cemetery. In this place was a school, stores, brickyard, church, post office, grange hall, and many other businesses. The Kanosha ferry brought many pioneers across the Missouri River on their journey westward, searching for what was the American dream in the 1800’s. Would we as 21st century Americans uproot our families and head out for the unknown, uncivilized frontier like the first settlers of Kanosha? I doubt that we would have the courage or the stamina to endure the hardships and make the sacrifices those early pioneers did. This is why it is important to remember them and what they did, and to preserve something of what they left behind.

It is only a little cemetery on the top of a bluff in southern Cass County, but in this day and age of absorbing into our culture the cultures of so many other countries, we may be losing touch with our own. In studying our past, we can come to a better understanding of who we are now as a society. In preserving our past, we are building a bridge for the next generations to understand who they may have become as a society.

* * * *

Works Cited

Amherst College Archives, Edward and Orra White Hitchcock papers, Series 11 & 9, URL: <http://clio.fivecolleges.edu/amherst/hitchcock/index.htm> 14 June 2006.

Andreas, Alfred T., and William G. Cutler. “Cass County.” History of the State of Nebraska. Ed Connie Snyder. Lawrence, KS: The Kansas Collection. 15 June 2006. <htt://www.kancoll.org/books/andreas_ne/hon_cnty.html>

Biel, Lavonn. Personal interview. 10 June 2006.

Carmichael, Maurice Kanosha Gravesite Record. Cass County Historical Society 1995

Condarcure, Steve “Steve Condarcure’s New England Genealogy.” 21 June 2006. http://newenglandgenealogy.pcplayground.com/sjc.htm.

Gilmore, George H., “Ghost Towns in Cass County.” Nebraska History Magazine, volume 18, No.3, March,1938.”Rpt. in” “The Plattsmouth Journal” Volume 85 1967.