2014 Issue

2014 Writing Awards and Selections for Print and Web

For her essay “Between a Kingdom and a Country: A Tale of Two Immigrants,” Sue Maresch is the winner of The Metropolitan 2014 Prize for Student Writing, a 13.5-credit-hour tuition remission. The first runner-up, Tina Piercy, is awarded 9 credit hours tuition remission for her story “Quiet.” The second runner-up, Elle Patocka, receives 4.5 credit hours tuition remission for her poem “If she wanted you to know her.”

Between a Kingdom and a Country: A Tale of Two Immigrants by Sue Maresch

Quiet by Tina Piercy

If she wanted you to know her by Elle Patocka

The Rook by William Sharp

A Green-eyed Girl by Janet Slottje

As I Recall by Luke Buller

Web Selections

A Step to Success by Angelica Juan-Lorenzo

An Excerpt from She Stopped Breathing by Elle Patocka

First Step of New Life by My Tran

If You Love a Flower by Molly Lieberman

My Spring Festival by Kang Tang

The Calling by Christopher Allan Loftus

The Day I Was Saved by Robert Rustan

Weeville by James Tuttle

Contributor's Notes

Luke Buller now attends UNO, studying English. He was born and raised in Omaha but wouldn’t mind eventually getting out to see the world. He is a huge fan of sports, football in particular, Notre Dame football to be exact. He loves to relax and listen to music. The Eagles, Led Zeppelin, and Tool are some of his favorites. He also loves sitting down and watching a good movie

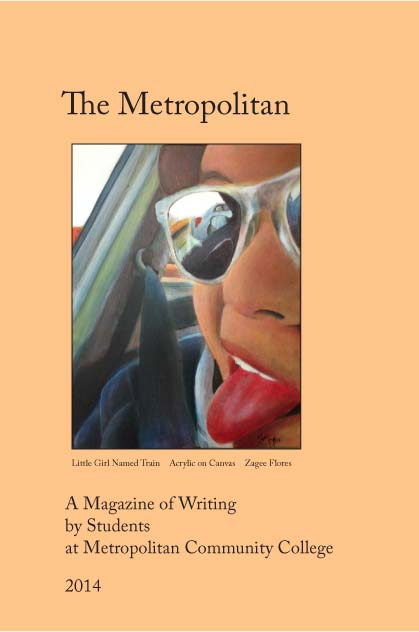

Zagee Flores never got serious about her art until her sophomore year of high school, but art was the best decision she ever made. Photorealism is everything to her in any medium.

Kris Freeman graduated from Dana College in Blair, Nebraska in 1975. She received her Master of Science from UNO in 1981. She retired from the Omaha Public Schools in 2009 after 34 years of teaching. A strong proponent of lifelong learning, she has enjoyed returning to the classroom as a student. She loves interacting with fellow students of all ages. Kris has always loved the creative arts and is now taking the opportunity to develop new talents. She enjoys drawing and painting, gardening, reading, golfing, interior decorating, carpentry, and playing the piano.

Molly Lieberman, originally from Michigan, has always had a passion for written expression. In her free time, she enjoys horseback riding. She is currently pursuing a career in healthcare and hopes to attend Nebraska Methodist College’s Sonography program next fall.

Sue Maresch was born in the northern Kingdom of Jordan and immigrated to America as a child. She is dual-enrolled at Metropolitan Community College and the University of Illinois, Springfield, where she is pursuing a BA in English. She plans to pursue graduate study to earn an MFA in Creative Writing so she may one day return to MCC and teach. She was so fascinated by her Children’s and Young Adult Literature class at UIS that she is currently working on a picture book of children’s literature entitled The Cupcake King, which she plans to self-publish this summer. When she’s not writing, Sue enjoys a variety of interests including Renaissance art, travel, and philanthropy.

Elle Patocka is a Czech lady born and raised in South Omaha. She has attended both Metropolitan Community College and Bellevue University to finish her degree in Communication Arts. She stays active with changing career paths, stand-up comedy, playing for the Omaha Rollergirls, announcing and interviewing racecar drivers at Eagle Raceway, road tripping on a whim, learning the ukulele, acting, baking cupcakes, reading all genres of literature, and writing whilst enjoying a cup of tea in her hammock when the weather permits, which is where “If she wanted you to know her…” and “She Stopped Breathing” came to life.

Tina Piercy is an Iowa native who, after working twenty years in the financial industry, became a stay at home mom of “Irish twins,” now 10 and 11 years old. For the past five years, she has worked towards her associate’s degree in liberal arts and dream job of becoming a writer. In 2014, she became the first person in her family to earn a college degree. She lives in Omaha with her very supportive husband, son, and daughter. She likes to golf, crochet, sew, write, read, and be active in her kids’ school. To fulfill her passion, Tina would love a job writing for a local publication. A blog might be in her future as well.

Robert E. Rustan, Jr. says writing this paper brought a lot of feelings he never knew he would revisit. He is glad he did because healing is talking about the situations. He enjoyed the writing and the struggles of getting this work done. He is very pleased with the outcome and the process he has gained. He realized he is a winner.

William Sharp an Omaha native, is in his last last quarter of study at Metropolitan Community College. He will be transferring to UNO for his undergraduate degree. His eventual goal is to become a doctor.

Janet Slottje was born in Omaha and raised in Bellevue, Nebraska. She has lived in the same house her whole life with her mom and two older siblings. She was the first kid of three who went to college right after graduating from high school. She hopes to be accepted into the Dental Assisting Program at Metropolitan Community College in the fall of 2015. She loves reading, especially on her Kindle. Renting movies and watching TV shows on Netflix are her next two favorite things to do besides eating.

My Tran is earning an associate degree in Business and will transfer to UNO to finish her bachelor’s degree. English was one of her first difficult subjects to confront with when she first came to the USA three years ago. It took her for a good two years to be able to understand and get her schoolwork done. That first step was not easy, but she did it.

James Arthur Tuttle was born in Denver, CO, but grew up on a farm in the hills north of Blair, NE. He attended MCC, UNO and has a BSN degree from Methodist College of Nursing and is currently working as an RN at the Omaha VA Hospital on the psych ward. He is a self-proclaimed hobbyist and enjoys writing about them. His non-fiction work The Basic Blacksmith, Next in Blacksmithing, and Primitive Bread can be found currently on Amazon.com. He attended recent classes at MCC to hone his writing skills in fiction to propel his writing career forward. James says, “Make time everyday to write, even if it’s just a little and soon it will add up to a book.”

Between a Kingdom and a Country:

A Tale of Two Immigrants

Sue Maresch

My father, whom I call Baba, was named after the second

King of Iraq, Ghazi ibin Faisal, crowned in 1933. My grandfather

told me once that Baba was fascinated with airplanes as a child.

When he grew older, he had dreams of riding the same biplane

that King Ghazi rode over Iraq, a magical aviatic carpet that

would fly him straight to America. “I was crazy for America,”

Baba said. “Everything I read or saw on the television fascinated

me. I wanted an education from America and to start a life here.”

One of five children of a retired Army soldier, my father

was born in March of 1935, the year of the Great Uprising, and

grew up in a small house in the center of town with his three

sisters and only brother Ghassan. He never knew his brother

George or the other babies who had died in infancy from malaria

or yellow fever. Even trips to the holy city of Nazareth and the

very streams from which the Blessed Virgin Mary drew water

could not save them.

Being a shy boy, Baba was coddled and pampered by

his mother, from whom he learned his soft mannerisms and

generous nature, and from his father he developed a love for

knowledge and sketching. He was quick of mind and excelled at

his studies, but he was often scolded by his teachers for sketching

in class. Short and awkward, he walked along the dirt roads of

his hometown of Al Husn, Jordan, with his sketchbook under

his arm and stopped from time to time to sketch the short, broad

wings of the sparrow hawk nestled in a Valonia oak tree or the

long, straight horns and tufted tail of the Arabian oryx grazing in

a field of grass.

Baba sketched cityscapes of America from scenes he had

seen on his black and white television, the Jordan Press, or on

film. “The cinema was only ten cents back then,” he said. “I

walked several miles just to catch an American film.” He was

exhilarated by the prospect of living in America one day, where

a man could pursue an honest life and not be denied his chance,

where its citizens may move freely within her vast borders

without hindrance or fear, a land brimming with opportunity and

freedom of choice. He waited for ten years to come to America,

teaching English to elementary school children in our hometown

to help support his parents and siblings. Finally, in the spring of

1963 at the age of 28, he left for America to fulfill his dream.

With 33 Jordanian dinars (the equivalent of 64 US dollars

today) in his pocket and dress shirts in his suitcase ironed until

they crackled like parchment, Baba set off to the great land of

America, the first son to leave home. In his pocket, he carried

a pack of Pall Mall cigarettes and a black-and-white photo of

Sophia Loren with whom he was enamored after seeing her

perform on screen in the 1953 film Aida. He left his family, but

he carried with him their memory and the determination to

succeed.

He first arrived in Omaha after following the advice of

a family friend who lived here. He needed to work and save

money for school, so he sold tapestries and artwork door-todoor with his friend Nabil. He then moved to Tempe, Arizona,

and attended Arizona State University, where he declared a

major in business. He continued to sketch in his free time and

took up soccer as a sport. It was there at ASU that he developed

another love: Western literature. He read with a great appetite

the works of Chaucer, Tolstoy, Dostoyevsky, Twain, Shakespeare,

Hemingway, Poe, and Faulkner and of the great philosophers

Descartes and Rousseau. I remember one day my father entered

my bedroom as I was reading a novel for literature class in high

school. “Kwais kteer,” he said. “Very good. One day my child will

grow up to teach fine literature like the book you are reading.”

He was referring to Mark Twain’s The Prince and the Pauper.

Although Baba was exposed to the great paintings of Van

Gogh, Degas, Picasso, Caravaggio, and da Vinci, sketching came

more naturally to him. On weekends when weather permitted, he

visited one particular congenial outdoor café off campus where

he would sip strong coffee and smoke his Pall Mall cigarettes

while sketching the passersby and parade of pedestrians that

filled the café—the great-breasted American women with wasp

waists and the men who courted them with slicked back hair and

broad shoulders. In my mother, though, he found true beauty

that came from devotion to her family, loyalty, generosity, and

kindness. A sketch of my mother in her early twenties still hangs

in their sitting room today. “So beautiful your mother was, more

beautiful than Sophia,” my father said with a childish smile.

“That was a long time ago,” my mother added, laughing.

My parents reminded me of how they came to marry. On a

return visit home three years after my father arrived in America,

my grandmother cried that her oldest son was still unwed. She

feared the laxity of America, that Baba would be drawn to

women not well suited for him, and that if he were to take an

American wife, he would lose touch with his country and his

family. This happened to one of my grandmother’s neighbors,

a charming woman named Khalood who lived next door. Her

cousin settled in Texas, married a petite Hispanic woman named

Esther, and never returned home.

Baba chose his distant cousin for a wife, a young girl of

seventeen with shimmering black hair. My mother Amal, which

means “hope” in Arabic, was the daughter of a poor, hardworking

farming family of seven children. Mama told me the story once

of how her family was so poor, she had to share her only pair

of shoes with her mother. She walked to school every morning

wearing the same pair of shoes that her mother had worn to

work in the fields earlier that morning. When she returned

home in the afternoons, she wore the shoes to complete her

daily chores. She tended to the chickens that lived on the roof

of the house and gathered milk from the goats to make cheese.

On Fridays and Saturdays when school was not in session, her

mother wore the shoes when baking bread in the oven, as the

floor was so hot from the steam. On those days, my mother

completed her outside chores in bare feet. “The ground was so

hot in the summers, but what were we to do? We couldn’t afford

shoes for everyone,” my mother said with a look of melancholy.

Everyone slept on floor mats in the main room, as there were not

enough beds or bedrooms. At her young age, my mother learned

of hard work, how to keep a meticulous house, and how to make

do when you have very little. My father asked my mother’s family

for her hand, and they were married three days later in early

spring of 1966.

My father returned to America after their wedding, and five

months later, after her visa arrived, my mother was reunited with

him. “The airline lost my only piece of luggage,” she recalled.

“I came here with only the black coat on my back.” My father

met my mother in Chicago, and they settled in Omaha, as my

father had made friends with a gentleman who owned a motel in

downtown Omaha, in the area where Midtown Crossing stands

today. Because my father had to work even more to support his

new family, he did not finish his studies at ASU. My mother

became lonely here. She was very young, spoke no English, had

no friends nor family, and she missed home. She didn’t know

what to do with herself while Baba was gone very long hours

selling tapestries, sketches, and art pieces out of the trunk of his

old Chevy Impala.

They rented a room by the week at the Hamilton Motel

at 33rd and Farnam Streets. The motel was a neglected building

with hallways that carried the overwhelming stench of stale

cigarettes. The rented room housed a squeaky bed, a sofa and

wobbly end table, a small armoire, a corner desk with a feeble

lamp, and a kitchenette. When she was fatigued in the afternoons

but couldn’t sleep, Mama sat outside on the front step of the

motel with her rosary and recited prayers in Arabic, working

the beads with her fingers while looking down at the shoes she

missed sharing with her mother. She sucked on lemon slices to

curb her morning nausea, and to pass time, she spent afternoons

at the city park across from the motel, feeding the pigeons bits

of bread. In the late evenings while she waited for Baba to return

home for the day, she watched a black and white television set,

but she could not understand the words.

Baba could no longer bear to hear her crying at night and

decided to send her back home to be with family until he was

more financially established and could afford a home of their

own. At least then she would have an infant to care for, as she

was pregnant with me and could take her mind off her sadness.

He planned that my mother would stay with my paternal

grandparents and aunt until after my birth, at which time we

would return to America to be with my father. By then, he hoped

to have a house, and my mother would be needed to arrange the

house to make a suitable home for us.

My father was not present at my birth in the winter of

1967, as he was still in America. When I was nine months old,

my mother left for America while I remained in the care of my

aunt, who was unmarried and had no children of her own. I don’t

remember the day my mother left, but I have some memory of

how I passed the time while my parents were away. I helped my

grandfather feed the chickens on the roof in the early mornings,

just as my mother had as a child. I threw the gritty chicken feed,

and dozens of birds scurried to the middle of the yellow grains. I

loved how they flapped their wings and was amazed at how fast

they could run when I chased them. My grandfather scooped

me up into his arms, hoisted me onto his shoulders, and pointed

to the West, toward the horizon, past the rooftops of the stone

houses and the open woodlands of olive and pistachio trees,

past the orchards plump with grapes. Baba and Mama were out

there, beyond the horizon, somewhere beyond where the clouds

disappeared and left only a faint blue light. I was finally reunited

with my parents at the age of three, in the spring of 1970.

My father worked day hours at Western Electric, and

my mother found a job at the downtown Ambassador Café

serving the lunch and dinner crowd. She took the city bus to

work, and my father picked her up in the evenings, as she does

not drive to this day. Over the years, my parents struggled with

raising seven children. They also sent $100 each month, which

was a lot of money in those days, to my uncle Ghassan, who

was studying medicine in Italy, to help with his expenses. My

father picked up overtime whenever he could, and there were

times when my mother held two jobs. We lived a simple life

without many material possessions. Christmases were spent

enjoying a traditional meal, reading passages from the Bible,

and listening to stories our parents told of their childhood. Our

needs were always met: we had food, a roof over our heads, and

good schools to attend. Although my parents made trips back

home to see family, those trips were few and far between because

of the expense of travel. In a span of twenty years, for instance,

my mother returned to Jordan on two occasions to attend the

funerals for her two brothers. My father returned home to

baptize his only son and when his parents died.

According to the Census Bureau’s 2009 American

Community Survey, the US immigrant population was

38,517,234, or 12.5% of the total US population. The number

of foreign born living in the United States increased by 1.5%

(about 556,000 people) between 2008 and 2009. Upon hearing

these statistics, my mother replied, “I imagine the hardest part

for all of us is being away from family. You come here, and you

are probably alone and know hardly anyone. You miss special

occasions with your family; you miss your parents and brothers

and sisters and nieces and nephews growing up. You miss your

old life, but as hard as it was then, it is even harder now.”

My father always held a very high regard for education.

Although my mother did not finish high school, my father

completed his undergraduate studies at Bellevue University. He

did this while working full time, caring for seven children in

the evenings while my mother worked, and driving my mother

to the grocery store, doctor appointments, and other errands.

I remember sitting at the kitchen table typing college papers

for him on our Brother typewriter because he typed with only

one finger. “On good nights, I slept about four hours,” he said.

“When your mother was working two jobs, I had to pick her up

at midnight and be up at 4:00 a.m. to be to work by five. I am not

sure how we did it, but we managed.” My father taught me that

you do what you have to do to accomplish your goals in life.

I recall a time when I was eighteen. We were in the midst

of a snowstorm, and my car wouldn’t start. As my father was

helping me jump the battery, we sat in the warmth of my car, and

I listened intently to him as he spoke to me. I had finished high

school earlier that spring and had not declared a major at the

university. I felt rather lost then, not knowing what direction my

life should take or what course of study would be best for me. “I

chose between my kingdom, where my family was, where my life

was, and this country,” he said with a somber look. “I came here

to make a better life for all of us, and a better life for you means

education.” He placed his forefinger against his temple and said,

“No one can ever take away what’s in here. When you figure out

what you want to do in this life, I will be standing right beside

you.”

Over the years, my father’s health has greatly declined. He

retired in August, 2001, and suffered a stroke a month later, two

days before 9/11. He suffered two heart attacks, bleeding in the

brain from a serious fall, and worsening dementia. His memory

remains strong for past events, but he does not recall recent

events. The day following my interview with him about his life,

he did not remember having been interviewed. He does not

remember that I have returned to college and that I wish to be

an English professor so I may instill in my future students a love

for the English language and literature just like he did. When

I remind him, he claps and says, “Good job, good job. I love to

hear that,” and then holds my hand tightly. This always makes me

weep.

As I sit here writing, I imagine what it would have been

like for my father had he not immigrated to this country. He

could not have publicly denounced his King without fear of

imprisonment. He could not have walked publicly with the

woman who would become my mother had they not been

betrothed or engaged. And I wonder what life would have been

like for me.

In the 49 years that my parents have lived in this country,

my father obtained a fine education and retired from a company

that provided an honest living with wages that helped to support

seven children, now all grown and successful. My parents are

free to worship, vote, speak and assemble along with the other

liberties they are afforded as citizens of the United States under

its Constitution. They are free to simply be happy. These are

liberties to which we are all entitled as citizens.

I am looking at a particular photograph now of me and

my parents taken shortly after we were reunited in America. Set

behind a grey backdrop, my mother is carrying me in her arms

with my father to her right. She is wearing a black coat with

black faux fur at the ends of the sleeves. Her hair is jet black and

shiny and curled just at the ends. She has large brown eyes, a

slight smile and a porcelain face with a beautiful cleft in her chin.

My father has black hair on the sides of his head and wisps of

hair at the top that are combed to the right. He has dark features

with brown eyes, small and kind, and is wearing a black suit and

tie. I am in the middle wearing a brown sweater, the ends of a

white undershirt peeking through. I have short black curly hair,

neatly combed and parted to the side, and I am wearing gold post

earrings. I am not smiling; rather, I have a look of curiosity.

We had no idea then what was likely or what was possible.

Quiet

Tina Piercy

Warren strolled home on a brightly sunlit morning with

his coffee in his wrinkled left hand and a newspaper tucked up

under his arm. The hot coffee cup in his hand reminded him how

he and his late wife of 48 years, Bennie, had walked this same

brownstone-lined block almost every morning together, admiring

the vibrant flower boxes and planters of each building.

As he reached the worn, familiar steps of his apartment

building, quick foot falls came up from behind him. As Warren

reached the first step of his apartment building, a young lady

stumbled into him as she clumsily changed direction from the

sidewalk to the apartment building steps. His right shoulder

jetted forward as she pushed past him, and his white, wavy

hair flipped over his forehead. Warren clenched his coffee cup,

worried steaming coffee would scald him, and grabbed the

concrete ledge with his free hand. He recognized her from

behind as his upstairs neighbor. He didn’t know her name, only

that she lived in apartment E7, directly above his D7. From

behind, her blond, shoulder-length hair tried to stay styled,

gathered together high on her head, but some of the hair didn’t

want to cooperate and seemed almost pulled out from the

restraint. Her extremely short dress was wrinkled and showed

her long tan legs. She grasped the penny-colored door knob, lost

her grip, and stumbled backwards. She caught herself with her

backside and hand on the rough concrete ledge railing of the

stairs.

“Hey! Watch where you’re going!” Warren seethed in her

direction.

Gathering herself, she balanced on her four-inch lucite

heels, clutched the knob with a firmer grip, and wobbled through

the big red doors to the apartment building without a look back.

“Damn kids,” Warren sputtered to no one.

He took his ritual steps back through the two large doors

and one step at a time the five floors of stairs to his apartment.

As he had gotten older, these fifty-eight stairs up and fiftyeight stairs down consistently put him in a foul, old-man mood.

Since his Bennie had died, he snapped nasty replies to innocent

questions and got frustrated easily. His cantankerous disposition

pushed friends and family away. He spent most of his time in the

apartment where his only son grew up before leaving for college,

never to return but for visits every five years, where Bennie died,

and where he would probably die as well.

He held tight to the wood railing up each step to his

apartment, stopping on the third floor landing between flights

to catch his breath. Out of breath, he didn’t rush to pull his keys

out of his tan, pleated pants pocket to finally open his apartment

door. He set his coffee on the doily-covered end table between

two arm chairs and the newspaper on the stained footstool

in front of the unused chair next to him. He sat in his once

overstuffed chair, the fabric on the arms worn thin, watching his

favorite TV show, Wheel of Fortune. The box-tubed TV with the

three channels crackled. He and Bennie used to watch the show

together, holding hands between their two stuffed arm chairs.

Warren admired Bennie for how quickly she could always get the

answers to the puzzles before each contestant could.

Midway through the show, Warren heard angry voices

from the other side of his old, worn apartment door. His chest

tightened in frustration at the interruption of the show. He

pushed up from his sunken impression in his arm chair and

squinted through the peephole but saw no one. He cautiously

opened the door to investigate as if a ghost might float by him.

At the end of the hallway, right before the start of the stairs that

led to the fifth floor, was the blond-haired girl from apartment

E7 from that morning. But now, her blond hair had escaped the

tie and lay ratted over her shoulders. Warren was about to give

the young lady another scolding, but he stutter-stepped exiting

his doorway. Almost involuntarily, he stopped. A man stood

next to the young lady with his hand grasped around her upper

arm, his knuckles white, her skin red and swollen between his

white knuckles. Black streaks ran down her cheeks, curving past

her chin, down her neck. Her eyes looked at the floor. The man

moved in closer to her, his teeth clenched, jaw muscles flexing,

saying something through his gritted teeth that Warren couldn’t

hear.

Warren hadn’t seen this man around his neighborhood

before. This guy had an Italian Mafia look about him. Slicked

back black hair, expensive-looking pinstriped blue suit, white

button-down dress shirt, and dress shoes that Warren thought he

could see his reflection in if he were closer.

“Hey!” Warren blurted out with urgency in his voice,

shocked these words had come from his mouth. “You two need

to take your lovers’ quarrel somewhere else. My hallway is no

place to be doing…this…whatever it is you two are doing here.”

The man jerked and turned. His eyes squinted at Warren,

and his white knuckles pinked up as his hand relaxed from

around her arm. The young lady exhaled, sniffled, and wiped the

black vertical stripes to horizontal smears. Her eyes in a trance

towards the ground, she wrenched from his weakened grip and

ran up the stairs.

“Hey ol’ man, we got no beef with you,” the Mafia type said.

“Just a lil’ disagreement with me an’ my girl is all.”

“Well, keep it out of my hallway,” Warren said as he gave a

get lost motion with a hand flick.

“Take it easy ol’ man,” he said with an eerie smile, taking

one step towards Warren in his apartment threshold.

Warren felt goose bumps over his wrinkly, gray-haired

arms. “Umph!” And he retreated to his apartment, where he felt

secure behind his two dead bolt locks, door knob lock, and the

bar lock across the worn door. He had known men like that in

his younger days. Men who were rough with their girlfriends.

But his Bennie was treated with the respect he felt all women

should be treated with. Doors opened and chairs pulled out.

Warren grumbled his way back to his old overstuffed chair

to finish the Wheel of Fortune show. One spin into the next

contestants’ turn, there were lumbering foot steps above his head.

He feared his ceiling tiles were about to crash down around him.

What were they doing up there? More shuffles and thuds, angry

muffled voices.

Warren angrily lurched from his chair, his heart beating

faster. His breath labored as he marched to the kitchen. Swiftly,

he grabbed his broom by the wooden handle and marched back

to the noisy intrusion that came from above his head.

“Damnit! Cut out the racket up there!” he yelled with a

quiver in his voice, thrusting the end of the wooden broomstick

at the ceiling three times. “Damnit!” he said breathlessly. He

tried to catch his breath, closed his eyes, took in a deep breath,

then let it out. The broomstick, still in his hand, shook. He

opened his eyes, looked around as if he could hear better with

his eyes searching for the noise, but heard none. He scowled at

the ceiling. His short temper had given his ceiling a couple of

round, white, chalked indentations, with the help of the wooden

broomstick.

“That’s right,” he proudly mumbled as he repositioned

himself in his chair with the broom dropped on the floor next

to him. He squinted at the ceiling, waiting for a response to his

parental thumps of the broomstick. He heard nothing. “That’s

right,” he said.

He cautiously settled back in his chair to catch the end of

Wheel of Fortune. He wished Bennie were in the chair next to

him, holding his hand and guessing all the right answers as he

beamed at her wide-eyed with pride. But the chair next to him

was empty, and he couldn’t figure out the answer to the ‘place’

puzzle with only two empty letters left.

Warren didn’t care about furniture updates. His old, faded

chair had character. Or new paint to brighten up the coffee colored walls. He didn’t care that his plates, bowls, and glasses

were all chipped, that his frayed bedspread was thinned and pilly,

or that the drapes were stained and thin.

Warren startled awake, confused. He wasn’t aware of when

or how long he had been asleep in his chair. The sun washed gold

and red over his thin curtains. A brunette robotic news reporter

on TV reported about another murder being investigated in the

city. He slowly raised his hands to his face, wiped crusty sleep

from his eyes, and yawned.

Clank. Bang.

Warren scowled at the apartment door.“Not again,” he

gruffed as he pushed himself out of his chair where his arthritic

old bones had sat still for hours. Teeth clenched and lips pursed,

Warren was ready for round two with the young lady and her

slick Mafia boyfriend. The locked door slowed him down. His

hand shook as his frustration built. Two dead bolts, locked door

knob, and locked bar. Out of breath with anger, he snatched the

door knob and flung open the door, ready to deliver a second

scolding.

Warren stood motionless in his apartment doorway as the

EMT workers rolled a gurney past his groggy eyes. The telltale

sign of death shown bright white just as he’d seen on TV shows

like Matlock and NCIS.

“What happened?” Warren gasped at a clean-cut man

dressed in a dark blue uniform with a red canvas bag with a white

medic symbol over his shoulder.

“The young lady upstairs was killed, sir.”

“Oh,” was all Warren could manage to eek out of his tightly

constricted voice box.

He had just seen the young blond with her greasy Mafia

boyfriend in the hallway. Now, her slender form under the crisp,

white sheet created a lump in his throat he hadn’t felt since

Bennie had died eight years earlier.

He stood frozen in his darkened apartment doorway.

Police officers and more EMT workers gathered in the hallway,

crisp dark blue uniforms blurring together in Warren’s narrowed

vision. A flash of red snapped him out of his tunnel vision trance

when the slimy Mafia-type boyfriend that the now-dead young

lady had been arguing with just outside his apartment door was

pushed past Warren. Glistening red liquid splotched down the

front of the once-crisp, blue pinstriped suit and white dress shirt.

Warren locked eyes with the man, trapped in the blood-soaked

man’s arrogant stare. A vacant sensation washed over Warren

from his throat to his stomach. His knees shook under his tan

pleated pants.

“Hey ol’ man, she’s quiet now,” he boasted, nodding his

head towards Warren. “She won’t be botherin’ you no more.”

If she wanted you to know her

Elle Patocka

When I die,

I want you to go through my belongings.

All of them.

Which should take you longer than you’d enjoy.

You won’t find much for yourself.

I am beyond sure you will bypass the most joy I lived through.

The small tokens of my life that can’t be found in boxes

or under the heaps of unfolded clothing.

Neither under the springs where I used to lay.

The go-to top closet shelf,

you won’t find anything there.

Nothing of my life in the frames upon the shelves.

Even the bookmarks of letters within the pages of the grandest

chapters I read.

Not even on the pages I dog eared.

You want to find my joy?

Don’t forget the pockets.

The jackets, coats and sweaters that hold the stitches of my youth

and adulthood,

leftover dinner mints, half pieces of gum, from moments of

enjoying fresh breath,

for my own liking or perhaps awaiting another’s lips.

Pins for hair, ticket stubs from films seen recently and years

before, or half-filled Chapsticks.

A poker chip, Hallmark cards ripped to pieces with vulgar spew,

soda-pop tabs and brew lids,

Fish hooks, dried out cherry and olive pits, napkins—with

writing and some with bodily sickness.

Pen caps and threads, used-up bandages, notes that brought us

away from the edge.

The jackets that jingle with loose change.

When worn, one can feel that there are objects within the back.

Insert your hand and find that I took no mind of ripped seams or

lost mementos.

Almonds once covered in chocolate, delicately sucked clean.

Werther’s of the original kind, paper clips, cough drops, flasks

and numbers to be dialed,

Chamomile tea ready to be brewed.

To the death within pockets

is what some might say.

A place which stowed away my moments.

To keep something for an unclouded day. You see,

it’s the pockets that kept me sane all those years.

They always gave me a small place to hide.

The Rook

William Sharp

Mason closed File #5 and moved it to the top of the stack

in the upper left-hand corner of his desk. He reached down to

his right, opened a drawer, and pulled out a half-empty bottle of

Macallan 12 Single Malt. Over his left shoulder sat a trash can

filled with brown-stained Dixie cups. Mason plucked one from

the top and with his finger quickly swirled the inside, removing

any old residue. He grabbed the bottle, inverted it, and filled the

cup to the rim. He grabbed the cup and shot the scotch down his

throat while he collapsed in his chair with his arms relaxed over

his head. His office was in the northwest corner on the second

floor of a five-story building in downtown Chicago at the cross

streets of Birkens Avenue and Armour Street. The flip dial clock

that sat atop a filing cabinet in the right corner read 11:47 p.m.

Storms had just begun to roll in, and the rain punished the halfcracked window behind him. The calendar that lay in the center

of his desk under a glass force field read June 27, 1979. It had

now been 23 days since the first murder. He could still remember

walking up the stairs of the abandoned building with the stench

of rotting pig carcasses and seeing the remnants of a woman

suspended in midair, strung up like a puppet over a blood-stained

mattress lying flat on the floor. This had been the worst murder

case he had ever seen, and a little over three weeks later, there

were eight more to follow.

There was a knock at the door. Mason quickly scurried to

hide the liquor at his feet.

“Come in.”

The door slowly opened with a screeching noise, revealing a

large, overweight man who stood in the corridor. It was Captain

Abrams. He had been the one who’d hired Mason right out of

school after he’d received his criminal psychology degree at the

University of Chicago. Abrams stood about 6’4” and weighed

well over 250 pounds. Once a former football star, he’d turned

cop after a bilateral knee fracture ended his career prematurely.

“How are the case studies going?” Abrams asked, moving

his body a few feet inside the doorway.

“Better, sir, if the bureau would quit stamping their fingers

all over my crime scenes before I have a chance to catalog

evidence.”

After the fourth victim, the FBI had decided to step in and

help out. Their young agents, however intelligent and motivated,

were inexperienced in chronological order of crime scene

manipulation.

“All right. I’ll see what I can do and follow up with you

tomorrow morning,” Abrams said while he turned for the door.

“Oh, by the way,” he added, sticking his head halfway back inside,

“Forensic says they have a match on one of the prints, and it will

be ready in the morning.” Abrams closed the door, and the sound

of his footsteps echoed in the distance and out of the hallway.

After a few moments, Mason retrieved the bottle, poured

another shot, and consumed it in the same manner as the first.

Mason laid files numbered one through eight out over the top

of his desk. He reached to the inside of his black overcoat and

pulled out a pack of Checker smokes. He packed them against

the inside of his left palm, ripped the plastic wrap, and tore off

the silver metallic paper. He pulled out a single cigarette, lit it

simultaneously while he pressed it to his lips, and then tucked

the pack back in place. He pushed against the arms of his chair

and stood into position overlooking all cases while smoke

smothered his head and rose slowly to the ceiling, lingering

at the top, just like the woman lingered in the photos before

him. The room became humid with the warm rain that blew in

through the window, which was now half fogged. Sweat beads

began to form atop his head, traced down the side of his cheeks,

and accumulated below his chin before dripping on the victims

below. In each crime scene, there was one similar identifiable

piece. A rook. In file one, it rested at the base of the bed. In file

two, it laid in her mouth. Three, on her foot. Four, in her hand.

Five, six, seven, and eight, it was stuck in the victims’ eyes and

ears. But why? In his undergrad studies, Mason once wrote a

paper on the ideology of the rook and the significance it played

with the psychological aspects of the human mind. It represented

a term of power or total greatness. This clue of trademark was

much more than the outlining of a killer, but instead it was used

as a legacy. Mason believed this to be a self-obsession.

Before moving to Chicago, Mason had attended a

community college in Missouri. During his final semester there, a

similar event took place. A young woman was brutally murdered

in her dorm room. The investigation lasted for months, and there

was never any arrest made in the case. This event eventually

sparked his departure from Missouri and to Chicago, where he

used it as inspiration for further pursuing his career.

The telephone in the upper right-hand desk corner began

to ring. Mason gazed up at the clock, 12:05 a.m. He was puzzled,

not only about the fact that it was after midnight but that

someone might know he was still there.

“Detective Mason,” he answered.

“Mason, it’s Abrams.”

“Yes, sir. What can I do for you?”

“Go to sleep, Mason. You’re too tired,” replied Abrams.

“Come again, sir.”

“Go to sleep, Mason. You’re too tired. You know the truth.”

“What, sir? What truth? Who is this?” Mason said, coming

off very hostile now.

“Do you not want to see the truth?”

Click.

The line went dead, and the dial tone now echoed in

Mason’s ear. He replaced the phone back on the holder and

grabbed the bottle of scotch. He pressed the bottle right to his

lips and took three slugs before he returned it to the table. His

vision started to double as the room became hazed from the dim

light. He folded both arms on the front of his desk and dropped

his forehead down into the center of them. I’m going crazy, he

thought. What the hell was that?

Mason lifted his head and gathered all of the files into a

single stack. On the floor to his right was a worn, black briefcase

with a gold four-digit number combination. He reached down

and grabbed it, placing the case next to the files on the desk.

Entering the numbers five-three-seven-eight, Mason popped the

lock and raised the top until it became vertical. One by one, he

carefully placed each individual file on top of another. He closed

the lid and snapped both locks into place. He grabbed the bottle

of scotch and pressed one more swig to his mouth and down

his throat before he returned it to the bottom right drawer. He

stepped out from his chair and tucked it under his desk. Mason

grabbed his case and started to make his way from around his

desk and to the office door. It had been a long night, and he was

getting very tired and a little drunk. Whatever his captain had to

say to him would have to wait until morning for an explanation.

He cupped the doorknob and started turning it counterclockwise.

Ring, ring, ring came from the phone for the second time.

Mason, determined to find out who was calling, executed

an about-face, picked up the line, and held it to his ear. He did

not say anything this time. He just waited.

“Hello, dear,” a female voice came over the phone.

“Elizabeth?”

Elizabeth was Mason’s former wife who had left him two

years prior. Mason, after a series of very difficult psychological

diagnoses, had fallen into a depression where he developed a

mood disorder and an extreme alcohol addiction that led to the

collapse of his marriage. His addictive personality just couldn’t

let go, so there was a restraining order placed on him, and he had

not seen her nor heard her voice since.

“Yes, Mason.”

“Why are you calling me?”

“The truth, they want the truth, Mason.”

“What the hell are you talking about? Who is this?”

Just like the call before it, the phone went dead, and a

dial tone echoed in his ears. As he moved it back to its spot, he

noticed the cord coming from the jack on the side of the phone.

He reached down and pulled on the line. His fingers followed

it down the side of his desk and behind a small side cabinet. He

grabbed the cabinet at the top and with his foot at the bottom,

nudged it back a few inches. The end of the line lay on the floor

with no connection to power at all. That’s impossible. Mason’s

heart was racing as he started to pace back and forth in front of

his own door. He reached down and grabbed the phone, lifting it

above his head and smashing it to the ground. Particles of plastic

and wire dispersed across the floor. He walked back around his

desk, pulled his chair back out, and sat down. He placed his black

case back on the center of his desk. Mason reached down to his

left to pull out his bottle of Macallan 12 for yet another drink.

He opened the drawer, his eyes widened, and his mouth slowly

cocked to the side.

The bottle of liquor was in the bottom right drawer. He

had always put it in the right drawer. He never went in the left

drawer. Mason reached in and pulled out a clear plastic bag and

set it next to the case on his desk. He entered his combination,

opened it, and removed all eight files. He moved the files into the

trash and out of his inner coat pocket removed his lighter. Mason

lit the corner of the files and sat back in his chair looking at the

bag. He reached inside and pulled out a single rook and set it on

top of his worn, black case. The smoke filled the room and carried

out of the window behind him. Flames rose to about three feet

before slowly dwindling down into small embers and ash. Mason

grabbed a Thermos full of day-old cold coffee that resided in

the back corner of the room by the window and poured it over

the top of what was left of the once raging inferno. Ashes rose

like fireworks lighting up a gray sky, sending a smell of plastic,

carbine, and vanilla into the already polluted room. Mason pulled

a pen, along with a single sheet of official, documented manila

paper out of the center drawer of his desk. He laid the paper flat

on the desk and began to write….

The weaker presence that resides in me is named Mason Kane,

but my true identity is Vladimir Kosovo. The first time I killed was

while I was attending college. Mason was always the brain, but he let

me out every now and again. I loved it so much. I can still remember

the feeling I had, stringing the wire through her body, in her mouth,

and out her eyes. I managed to take special care not to damage any

of her natural beauty. It had taken hours to correctly assemble my

creation. Once I had finished laying her new metallic veins, I raised

her to the ceiling, like a puppet master pulling her strings. I licked the

blood that rolled down the cords and rubbed it all over my face and

hands. Mason never trusted me again after that. He locked me up,

and then, over the years, he forgot where he put the key. I became a

bad dream, a dream that never really existed. He thought he could

silence me? Through his alcoholic tendencies and self-induced comas,

I had managed to find a way out. While Mason would be asleep, his

body would be awake. I had returned. Picking up were I left off, I

found my first victim walking alone outside his apartment. It was like

riding a bike. The taste returned like it never left, but technique took

time. That was okay. I had several more attempts to perfect it. I was

very careful to lay fraudulent prints all over each woman, but it was

only by chance that Mason ended up with the case. How perfect. So I

concealed my actions even from him but made sure I left a clue, a piece

to the puzzle that would allow me to finish my work and lead him to

my overall existence once more. I will not make the same mistake he

did. The key to his tomb in which I locked him no longer exists. I am

Vladimir Kosovo. I am the Rook.

Vladimir left the note on the desk and exited the office.

Turning one last time, looking back, a faint smile rose upon his

face as he disappeared into the darkness like a broom to his very

footsteps.

A Green-eyed Girl

Janet Slottje

It was an average day in the fall of 2002. My seven-year-old

daughter, Abby, was just getting let out of school at 3:10, and I

was waiting to pick her up in a green, two-door, beat-up Toyota.

It was still nice enough outside to have the windows rolled down.

Kids piled out of the school, so I knew she would be out soon. I

wondered what my other two kids were doing. She saw me and

smiled and waved as she got closer to my car.

“Hey, sweetheart, how was your day?” I asked her when she

got buckled up in the passenger seat next to me.

“It was good, Daddy. We played kickball at recess today, and

my team won!” Abby replied.

“Wow! Way to go, sweetheart! That’s three times this week

you’ve been on the winning team,” I said as we started to leave

the school.

Abby looked up at me with big green eyes like a dog

begging for a treat and asked as nicely as possible, “So, do you

think we can go to Walmart and get those shoes we saw the

other day? These shoes are really starting to get worn out and

dirty.”

“Well, I don’t see why not! You can’t be the best kickball

player if you don’t have the right shoes, so to Wally World we

go,” I said. I could see the grass and dirt stains on her blue jeans

as I leaned over to grab the Budweiser by her feet. I put it there

because it was too big to put in the cup holder, and I didn’t want

people to see it when they drove by. I twisted the forty open and

took a few gulps, sighed, burped, then placed the beer between

my legs, so I wouldn’t have to keep reaching down by Abby’s feet.

It was my first beer of the day, but it certainly wouldn’t be my

last.

I took my time getting to Wally World, so I could smoke

another cigarette. Drinking beer always made me want one.

Smoking Marlboro Lights 100’s was like smoking air, so I

smoked them often. Abby enjoyed looking out the window as

we drove. Every time I glanced over her way, all I would see is

the back of her blond little head. Her skinny little legs were just

as skinny as mine. She was a spitting image of me besides the

freckles that masked her face. When I would think about Abby

and who she was going to be, I couldn’t help but reach for the

bottle and take a few more gulps. I didn’t want her to see me

like this all the time. I didn’t want to fail as a dad to Abby. Abby

deserved better than me. So saying no to her was very difficult

because I only wanted to see her happy.

We pulled into the parking lot of Wally World, and I

parked by the auto entrance on the north side of the building,

away from the main traffic in the front of the store. Abby looked

up at me again and smiled while she waited for my cue to get

out, and I could see the excitement on her beautiful little face.

“You ready, sweetheart?” I asked her with a yellow smile.

“Oh yeah, Daddy. I am!” she replied. She almost sprinted

to the door from the car, but she always kept me in eyesight.

My long legs didn’t have trouble keeping up, but damn that girl

was fast. I had finished about half of that forty on the way there,

so I was feeling a bit buzzed and really good. The cigarette I

smoked covered up my beer breath pretty well, so I didn’t feel

paranoid walking into the busy store. We made our way to the

shoe department, and Abby walked down the aisle with her hand

running across the other shoe boxes until she started hopping up

and down when she spotted the pair of Champions she wanted.

“Try them on, sweetheart. You need to make sure they fit,” I

instructed her.

“All right, Daddy,” she said.

I watched her skip to the bench, and she threw her old

shoes on the ground like they were trash and tore into the new

shoe box. I couldn’t help but smile because I knew she was happy,

and seeing her happy made me happy.

“They fit perfectly!” she exclaimed.

“All right then, let me see.” I knelt down in front of her and

pressed my thumb on the top of the shoe where her big toe was

supposed to be, and there was about an inch gap between her toe

and the front end of the shoe. “You’re right, sweetheart.There’s

enough room for your feet to grow, so let’s get these.”

She smiled really big at me, then at the shoes, then back at

me. I could feel the love bursting out of her pores like the beer

bursting out of my own. She packed the shoes back in the box

nice and neat, and we made our way to the checkout. I couldn’t

buy her anything else because I had to be cautious about how

I spent my money. It wasn’t mine after all. It was my mom’s

because I didn’t have a real job. I had been living in my mom’s

basement since after I got divorced in ’93. Abby was conceived

right before the divorce. She didn’t have to witness the abuse and

mayhem I caused my other two children and my ex-wife during

the fourteen years I lived in that house. I was too worried about

getting hammered to pay attention to who was most important,

my kids. Abby was lucky enough that she didn’t have to witness

an abusive father. She was my last chance to prove that I wasn’t a

complete failure. Abby skipped to the cashier.

“Is that it for ya, honey?” said the overweight, plain lady

behind the counter.

“Yep, that’s it!” Abby said. “Blue is my favorite color!” she

exclaimed while the lady checked the size of each shoe to make

sure they were the same.

“These shoes look awesome! I bet you can run faster than

anyone else at school with these! Now just remember to take care

of them, and did you thank your father?” The lady smiled at me. I

chuckled.

“Oh yes, thank you so much, Daddy!” she yelped. I felt like

a good dad. I felt like I was finally doing something good for my

kid.

I needed another drink, so as soon as we got back in the

car I chugged the rest of the forty. I lit up another cigarette and

got the little black comb from my pocket and combed back my

balding blond hair like John Travolta in Grease. We started to

make our way back on Highway 75 south towards my mom’s

house. I threw the empty Budweiser out the window so there

wouldn’t be any evidence. I saw that Abby was clinging onto

the shoe box like her life depended on it. I looked at her for a

minute and took in all of her beauty. She was so beautiful for a

little seven-year-old tomboy. I knew she would grow up to be

something really amazing for the world. My head started to spin,

and my buzz had turned into something more, and I knew I

couldn’t go back to my mom’s house drunk, especially with Abby.

Instead of getting off at the Bellevue exit, I continued south

towards Plattsmouth because I figured I would just drive until I

felt sober enough to go home. Abby seemed a little confused and

glanced at me with a concerned look on her face. I smiled and

winked at her, and she just turned back to the window.

I turned up the radio and started to jam out to a rock song

that was playing. I was too drunk to remember the words, but it

felt great grooving along. Abby got a kick out of it and started

to giggle at me. I was feeling really good. I loved feeling good

and wondered why I couldn’t feel like this all the time. After the

song ended, it went to commercials, so I turned the volume back

down. My buzz started to fade while we arrived in Plattsmouth.

I started to feel very drowsy, so I lit up another cigarette to wake

myself up a bit. I followed the main road for a bit then turned

slightly right up a hill because I knew I was getting drowsier.

Things went black….

“Dad! Dad, stop!” Abby kept repeating.

“Oh shit!” I said as I slammed on the breaks. We sat there

out of breath for several minutes. I was confused. “What the hell

just happened? Are you okay?”

“We almost hit that dumpster. I’m fine, Dad. Let’s just go

home,” Abby responded in a calm voice.

“Yeah, good idea. Let’s go home. What do you want for

dinner?” I asked her as I lit another cigarette.

As I Recall

Luke Buller

I sat and I waited

On our two front steps.

Concrete chipping away from the salt,

But why fix it?

On this cold, Friday evening,

The second weekend of the month.

The sun was still shining, however. I

Stayed out of the shade for warmth.

Beautiful colors of leaves flutter around me.

They remind me of butterflies,

Such beauty and grace.

I run up to the sidewalk and look down both ways.

The dead trees hang and bow down to the street.

They, too, are waiting,

To welcome him, I’m sure.

I run back down the stairs and fall in the grass.

The wind is a like an ocean.

Its current controls me.

Such innocence now, as I recall.

Jeans torn on both knees,

To be young again. Just for a day.

Before scars were found deeper than the skin.

A phone rings inside.

I walk slowly towards the screen.

My mother hangs up, looks at me,

And mirrors my face.

There is no happiness here.

A Step to Success

by Angelica Juan-Lorenzo

I wondered how my life would have turned out if I wasn’t a US citizen but an immigrant that is migrating to the United States from their hometown to what some may call a “successful life” or the “American dream.” I have heard many people say “immigrants come to the United States to take our jobs away,” or “they should go back to where there from, they don’t belong here.” We must think before we speak, and put ourselves in other people’s shoes to understand the situation their in, not judging by their appearances right away. Many immigrants that I have spoken to say because they’re tired of the situation their living at their hometown and most parents don’t want their children to suffer in the terrible conditions they did when they were growing up. “Hmmm, that’s what my father told me,” I said to them.

As we gathered around the couch in an afternoon, getting comfortable and ready to watch our favorite news channel, Alarma TV had started, and we were all ready to hear what was going on out in the world. As we turned up the volume, a story came up about the poverty in Guatemala. People were getting murdered and kidnapped, and men in black were breaking into houses. “Ay dios mio” said my mother, scared because it keeps getting worse in Guatemala, and she was also worried about her mom.“Ma, don’t worry. Nothing’s going to happen to grandma” I said to her, trying to calm her down.

I asked my dad how life was back in Guatemala. My father began to have flashbacks and remembered. “Let me tell you a story,” he started. “When I was about 13 years old, I had no decision but to not go to school anymore. I had to drop out. I had to help my family earn money because we they no longer could afford my education nor that of my siblings. In Guatemala, children are being forced to work and have no other obligation but to follow the rules and do what they are told to do. The children work so that their families can survive” my father told me as he stopped to sip a glass of water, ready to tell me what happened next. “For example my cousin and I, we worked looking for things in the garbage so he could buy beans. His family has a piece of land that they built out of metal sheets, plastic, cardboard and many other materials that they found in the garbage or with the little they can afford. In the afternoons, we worked making fireworks, nine hours a day the whole week. We struggled to survive from the income we earned, and we were exposed to explosive chemicals.” He stopped to think. “That’s why I want you guys to put your education first, and not follow our steps,” he said, while mother walked into the room agreeing to what he said.

My father decided it was time to leave Guatemala and everything behind in 1994 because he was scared of dying and he wanted to do something better than working in places where it could cost him his life. My parents made plans to head to the USA to find opportunities for their children, and to escape poverty and child labor. They were ready for a change.

I couldn’t believe that they were forced to work by their parents in order to have food on the table and not starve. It was something I learned about my parents that day. Later that day, I asked my mother that if she had to go through the same thing as father or how life was for the girls. “No mija, its different. The men work at a really young age and stop going to school. And well, the women are a different story. When I was little…” she started, “your grandma tried to sell me to someone that liked me for his wife and to have kids with. But I didn’t like that man, the man your grandma was trying to sell me to. He was a stranger to me. We needed food and we were really poor. My mom forced me to go with that man that day. I tried to escape because I didn’t want to be sold. When your grandma found out that I disappeared, she hated me for not marrying the man that she chose for me. That man was around his 40’S and I was only a nine-years-old,” she said. We sat there for a moment, silent because mother started remembering those moments and why her mother rejected her for so long. I couldn’t say anything, I had nothing to say. My mind was blank like a piece of paper. It was wrong what my grandma did to my mom. There was just so much that I learned that day and it was about my parents’ life.

Taking the decision to cross the border is risk taking; I bet it was a hard thing to do for my parents and others that have gone through the same or even worse conditions. It is inherently dangerous. They could be deported back to their country, being caught by the border patrols, excessive heat, no water, death, dehydration, etc. Migrants face higher risk of death in the desert than any other place. Border patrols have found in the dessert bodies of 93% of migrants crossing for a dream as an American. My parents went through what many migrants did when they crossed the border to their dreams. My mother, Angelina, walked in the desert with her youngest son wrapped in a cloth on her back. Her biggest fear was that she would not make it and that the baby would get sick because of his wet dirty clothes and die. Most immigrants have that fear that they would die crossing the desert because of no water and that they wouldn’t be able to see their family again. They knew it wasn’t a good idea to take a one-year-old through the dessert, but it was too late to go back. They had already made up their minds. Crossing the border was one of the many steps to America. My father, Francisco, held up my mother because she grew weary and tired. He had to carry her because she was too weak to walk.

Baby Miguel cried constantly. They had no more food to feed the little one. “How did Miguel eat if there was no more food?” I asked. “Es que a nice lady had a little bit of food and water. She heard the baby crying. So she got up and gave it to me in my hands,” she said with a smile on her face, feeling so blessed that that lady offered to give up her only food to the baby. I could only imagine how hurtful it would have been for my parents if they had lost their baby.

“We’re almost there, call your families to pick you up. We are stopping at Los Angeles, California,” the coyotes said. When they received the news from the coyote, everyone laughed and cried with joy. Some were to be united with their families for the first time. Others were here for a better future. When they arrived at Los Angeles, California everyone was to leave the truck and from there they were on their own. My dad had family in California, so they stayed at their place for a while till my father got a job.” When we arrived at the house, there were about fifteen people in a two bedroom apartment,” she said. I was shocked, well not as much because we rented a house of two bedrooms and there were about thirteen people in the house.

For my father to get a job in the United States was very difficult because he didn’t have papers. He was afraid that if he was to be hired, that immigration would come in and take him back to Guatemala. “It was difficult. They all asked for legal papers,” my father said with a sincere look in his face. His life turned around. “I was so stressed out because they were asking me for the rent. I had no job or money. I drank with the little money that I earned helping out a friend,” he said. My mother walked into the room and she said “He wanted to go back to Guatemala. He couldn’t help me out with the babies’ food and diapers.” But after few weeks they looked for help from a friend.

They contacted a friend and spoke to them about their situation and how they had just moved to the US from Guatemala, and that they were looking for a job and a place to live. They decided to travel to Omaha, NE. Here in Omaha, their friends helped them put in an application to apply for a work permission in the US. They applied in 2000. Six years later, we heard the news that they were legal in the US. “Gracias a dios,” said my mother with a huge smile while tears rolled down her face. Father found a job working at a baking company. “It’s been eoght years with my residence,” my father said with pride. One thing that I admired more and more about my parents was that they have that mentality of a conqueror. They will not stop just as residents. They have been taking English classes to prepare themselves to apply to be citizens. “Wow, dad that’s awesome!” I said.

Immigrants come seeking opportunities that you and I have as citizens. They come to seek help, and to give their children the best: an education and everything else they couldn’t receive when they were younger and to have a bright future full of opportunities that will take them to a new level of learning. Everything takes a process, but it all leads to success and a better living situation. Migrants risk their own lives because they believe that there’s something beyond if they go and fight for what is theirs. Passing to the border, poverty, and child labor is a part of someone’s life. Coming for a better life means steps. Steps is a life of an immigrant. They believe everyone deserves a chance to experience the “the American dream,” the land of “success,” the land of opportunities.

An excerpt from “She Stopped Breathing”

by Elle Patocka

I woke up realizing I had left my contacts in and I went to the restroom to take them out and put on my glasses. I saw the TV first. It was on some morning bible program. I scanned the room and saw my mom’s sister with her head down on the hospital bed, and then I saw my mom’s face. Her eyes were open, something that hadn’t been for the past days since she was on morphine. Then I noticed her breathing. Short, short, shallow, short, short, gasp.

“Go get help now!” I yelled to my aunt. She quickly rose and left the room.

“Mom, wake up! Hey, I’m here. It’s Elle, let’s talk, Mom.” I had no idea what I was doing; I wasn’t a comforter. I just saw her eyes glued to the screen.

It had to have been only six or so in the morning, and I remember leaving the room and dialing my brother, sister, and best friend.

“Get here now!” was all I had to say. I noticed my aunt walking the halls and saw no nurses en route.

“I need help! Now! Someone! She’s dying!” I yelped hoarsely.

As I re-entered the room, frantic, I went to the restroom. Having just put my glasses to rest and my contact lenses to good use so, god forbid someone should see me look like the unbridled death of a woman in the a.m. Two nurses were there now with me, and they shut the door behind them.

“What are you doing? My family is on their way. Please keep the TV on. It was turned here when I woke up. I think she’s watching it,” I said. I stood at the side of the bed looking at them, placing my hands from my stomach to my head in wild motion. One nurse was checking Mom’s pulse and had a stethoscope on her chest.

“Please, come here and talk to her. She would want that,” A nurse said to me.

“I can’t.”

“Please, she’s your mother.”

Those words etched their way to my core, and I stumbled over and wiped my face and took my mom’s hand.

I could feel her twitching and see her eyes trying to search for something. I tried to not look at her face because I could see her mouth opening, gasping for any ounce of air. I focused on her chest and the sound of silence aside from the stethoscopes scratching on the fabric. I looked down and saw my mom’s hand, so I grabbed it. It was still warm, so that told me she was still alive.

“What do I say?” I asked

“Just help her feel comfortable and let her know you’re here,” a nurse replied.

“Mom? I’m here. It’s Elle. I’m so sorry. Please don’t be afraid. I love you. We all love you.” Word vomit spilled from my dry mouth. I couldn’t break at this moment because I had to be strong. I had to prove to my mom that I was like her, a fighter and a survivor.

I remember caressing her arm and finally looking up at her face. I think I said something to her about finding her mom and our dad up there and to not be afraid, at least I think this is along the lines of what I said or what I wanted to say. The words next made my stomach drop.

“Please. Wait for us one day, Mom.”

It was a few seconds and I felt the warmth start to leave her hand. I started to say “oh God” a bunch of times and kept asking if my mom could still hear me, and then things just went blank. The nurses left, and I was alone in the room with my mom’s body, until everyone starting showing up.

I look back now and wonder why I had to tell my mom it was me there with her, repeating my name like a fool. Why was it me? I had to let her know it was me. The one who couldn’t be there before, but I was there now, like it mattered, but it did. It did.

“What’s today’s date?” I asked the nurse outside of the room.

As she taped a rose to the door and answered me, I just half smiled and said, “It’s weird, she was born and died one day after Elvis. I sure hope he’s wooing her right now.”

You know how they say it seems like a one second moment before it all ends? That’s the truth. I don’t know how I managed to wake up, take out contacts, scurry for help, make three phone calls, put contacts back in, and watch my mother’s life end in my hands in the matter of a second. But I did.

“What are we going to tell everyone?” we asked one another as we waited for more family to arrive to view my mom’s body lying lifeless on the hospital bed peacefully.

“No one deserves to know shit!” I said.

Even though we all knew this day would come–it could have happened months earlier–none of us were prepared for this morning, and anger filled us. All three of us kids, under the age of 30, were losing our last person who brought us into this world. Indeed, we had been through this before. Nearly six years earlier, our father had died. Talk about how effed up life is. It’s unimaginable how to react to hundreds of people with the same-I don’t know how you kids can cope-look.

“Everyone will want to know every goddamn thing, so I’m blocking everyone out.”

August 17, 2011 via mobile to facebook

“Into paradise may the angels lead you”. TEOM

…

A week before mom passed, a home nurse came by to talk to her. These visits always made me uneasy because I felt I couldn’t assist my mom the way everyone else could. I’d listen in on her conversations. She said to the nurse this day:

‘‘I don’t want to die. It scares me. It’s not fair. Why me? I’m not ready…’’

I stepped in and said, “Hey, none of us do. Now you’re not going to, so stop fretting, lady!’’

I was crass, trying to be funny, but as I said that to my mom, she had the deepest sadness in her eyes, and I finally saw that she was afraid. It must have been the look I gave her when I was afraid of the monsters under my bed and being a small child looking for my mom to scare them away so they couldn’t harm me. But the monster my mom had inside her was one I couldn’t help scare away. No amount of night lights or hiding our heads together under a blanket were going to kill this monster or send it back to its other land. Jesus, the more I recall this instance, the more I regret not being honest with her that day. I might have said something like, “Yes, you are going to die. We don’t know when because such is life. It is okay, though, because you will forever live on, Mom. You are ‘one tough bitch’. You brought three children into this world, and no matter where we each end up within our lives, we will forever defend your honor and keep hope alive. Don’t be fearful of that.”

F***ing cancer!

First Step of New Life

by My Tran

As my alarm went off, my feet hit the floor, my stomach lurched, and I felt as scared as a child on her first day of school. Although I was frightened, I also felt very excited at the same time about my new school since I came from halfway across the globe to attend. My biggest worry was the language. I had been anticipating this day for a good while. I imagined in my mind how this day would go, the people I would meet, and I always ended up with worrying thoughts. “Would they understand me?” I pondered, “Would I understand them?” or “Will there people who don’t know English like me?” With these thoughts swirling in my head, I went to sleep the night before anxious and anticipating the events of the first day of school.

When the heat of the summer dissipates and the leaves start changing colors, fall is a time of changes. Fall is not only a time of changes for the weather and trees, but also a time where many young adults start the first step on the path of entering a university to build a career and a life. America is known as the land of opportunities where, with hard work and determination, one can achieve anything one can dream of. It is these ideals that have brought me halfway around the world from my birth country of Vietnam. I knew the journey would be difficult and filled with challenges that would test my resolve and my will.

One major hurdle for immigrants to America is learning the language and adjusting to the culture. Oh, let’s not forget the weather. Coming from a tropical country, I was rudely introduced to the harshness of a Nebraska winter. I never knew people could live in a place as cold as or even colder than a freezer. In Vietnam, every day the weather is in the 90’s and that is year round, so any temperature remotely close to being cold is unheard of. Like the weather, I knew it would take time for me to adjust to life and school in America. I had hoped it would go smoothly but knew that because of my limited English, it would have to take time and patience.

I woke up on the day of Orientation feeling nervous and uneasy. I went into the bathroom to get ready. This might be unusual, but the bathroom is usually where I am thinking and contemplating about things and events in my life. Standing in front of the mirror brushing my teeth, I rehearsed and practiced English sentences that I knew I would need, sort of like a singer letting out a few high notes before the curtain goes up. Although nervous, I wanted to look my very best on the first day of school, so I wore clothes I just bought the day before at the mall. It is my belief that when you start on a good note and feeling good about yourself, luck will be on your side.