2015 Issue

2015 Writing Awards and Selections for Print and Web

For his poem “It’s Pronounced Bis-koth-ah,” Joseph McGuire is the winner of The Metropolitan 2015 Prize for Student Writing, a 13.5-credit-hour tuition remission. The first runner-up, Ryan Redler, is awarded 9 credit hours tuition remission for his poem “Maryjane and Chicken Soup.” The second runner-up, Laurie Jordan, receives 4.5 credit hours tuition remission for her story “The Bank”

It’s Pronounced Bis-koth-ah by Joseph McGuire

Maryjane and Chicken Soup by Ryan Redler

The Bank by Laurie Jordan

Freak Show Funeral, Just a Cook, and The Bridge by Nate Detty

The Eight Stages of Loss by Amanda McLeay

How My Jazz Turned into The Blues: Sonny’s Side of the Story by Douglas Anderson

Number Nine by Terry Grigsby

Web Selections

Ode to Cucharitas by Carissa Caudillo

Altruistic Understanding by Ryan Redler

Contributor's Notes

Douglas Anderson was born into a working class family in the heart of South Omaha’s meat packing industry where he still lives today. After graduating from Omaha South High, he enrolled in an apprenticeship program and later attended classes at the University of Iowa’s Labor Center. When an injury ended his career in construction, he resumed his education at Metropolitan Community College among an exceptionally diverse population that helped to solidify his belief that there are no absolutes and nothing is black and white in the world, only lenses that make it appear that way.

Carissa Caudillo is a student and a learning writer in Omaha, Nebraska. She has always enjoyed writing and has always wanted to get published. She enjoys writing both essays and stories and hopes to write a book someday.

Nate Detty was born and raised in Scottsbluff, Nebraska, although he has lived in Lincoln and Omaha for the last fifteen. He has spent the entirety of his adult life working dead-end restaurant jobs and living in relative poverty in order to develop the angst needed to write creatively. Although his head is still pressed firmly against the glass ceiling of those same dead-end jobs, he is now furthering his education by studying the liberal arts at Metropolitan Community College. He enjoys writing and thinks of it as a cathartic way to organize his thoughts and make sense of the world around him. He hopes his studies will help him to hone his craft. Laura Dick is currently a student in the commercial photography program and will graduate in November 2016 with her associate degree.

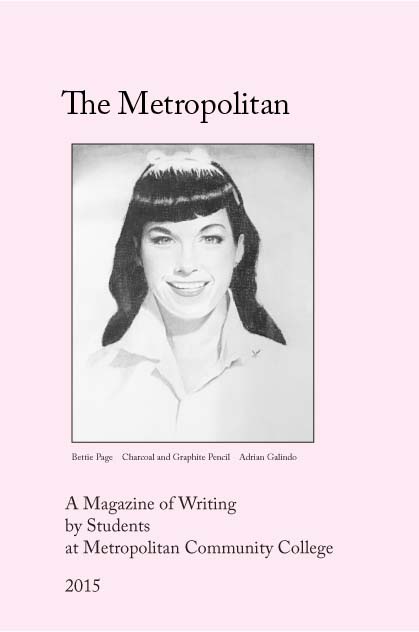

Adrian Galindo is a Hispanic artist based in Omaha, Nebraska, who specializes in photo-realism portraits and still life. While he is mainly self taught, he received formal instruction at Metropolitan Community College. Bettie Page has been a muse and inspiration to him from an early age, and by drawing her in black and white, he hoped to emphasize the facial aesthetics of a 1950s cultural icon.

Laurie Jordan is a Wisconsin native but has lived in Iowa most of her life. She and her husband Jeff have been married for twenty four years. She enjoys traveling and has journeyed to many historic and exotic locations. Laurie is a former hairdresser and spent twelve years behind the chair before deciding it was time for a career change. She has been working for Nebraska Furniture Mart for the past sixteen years. In between working and taking college classes, she spends her time walking for exercise, thrift shopping, planning vacations, and binging on reality TV. For the past five years, she has been working toward her associate degree. She plans to transfer to Bellevue University after she graduates from Metropolitan Community College.

Joseph McGuire completed his credits at Metropolitan Community College last summer and is currently finishing his undergraduate work at University of Nebraska at Omaha in Health Administration. He will be starting the MA in Sociology program at UNO this fall.

Amanda McLeay was born and raised in Omaha, Nebraska. She recently graduated from University of Nebraska at Omaha with a degree in General Studies with an emphasis in Art, Architecture, and Communication.

Ryan Redler was born in Omaha, Nebraska, on July 21, 1984. He was educated in the Omaha Public Schools and attended Metropolitan Community College in Omaha. He was encouraged to continue writing by his teachers as he showed great promise as a writer. Ryan spent a year in the Philippines working in the orthodontic industry and traveling in Asia. He is a self-taught guitar player and loves to write his own songs. Ryan has a great love of writing and hopes to become famous.

It’s Pronounced Bis-koth-ah

Joseph McGuire

Her Italian kitchen is sacred space; a consecrated

room gathering us together, sustaining flesh

and restoring spirit. Between oven and sink

lay a wooden altar whose legs mark

our maturity in carved notches, signs

indicating our readiness to accept her Magi gifts.

First, a lesson in frugality; a frivolous swing of the icebox

door is a dime wasted. Second, a sepia aged recipe card written

in her calligraphy-scripted hand. Third, the delights

crafted from her culinary tutelage had a most powerful name,

and it was pronounced “bis-koth-ah.” Not biscotti.

Her biscotti are not the familiar cafe cookies, plastic

wrapped and stamped with sell-by dates. They are not

traditional, twice-baked hard and cracked desert dry

needing to be quenched in coffee or wine, yielding

just barely enough for softened palatability.

No, her biscotti are delicate pastry pillows, glossy

with crystalline glaze draping the airy morsels in sweetest sugar,

flavored with extracts of star anise and citrus, cocoa and mint,

tasting of weddings and heartache, baptisms and funerals.

Her biscotti hijack the linoleum-clad, avocado-hued

kitchen, transforming it into an all-day aproned assembly line.

Mounds of dough blur by, rolled and divided on floured boards,

hooked arthritic hands showing no signs of fatigue.

Fired and finished, they rest, laid cooling in metal bowls.

Her biscotti store well, a blessing

now that she’s gone.

The essence of my mother’s mother lingers a moment longer

in air-tight Tupperware boxes, carefully arranged and rationed

frozen memorials greeting me every time I waste a dime.

Maryjane and Chicken Soup

Ryan Redler

I’m from where the fireflies rise

at dark park at twilight,

waiting for my lover.

I’m from lamplight and no cable.

I’m from mail envelopes and scraps of paper

with poems and phone numbers scrawled upon them on

the table.

A kitchen knife sharpened brick pencil, with no eraser,

or eyeliner on my pencil tip,

sharpeners from my mother’s makeup bag.

Just charcoal and berries,

drawing on the cave walls,

hand prints, and antelope,

might as well

throw in a mammoth,

and some spears,

just to make it high tech.

That’s where I’m from.

I’m from,

Honey what day is it today?

and

Will you read this for me? It looks important.

I’m from Maryjane in the air,

and the smells of homemade chicken and

noodles

simmering on the stove top.

I’m from

aspirin fixes everything,

and no doctor visits because we have no insurance.

I made it through.

I did.

My kids know to head home when the streetlights come on.

My kids know how to pray.

My kids know I love them.

My kids know that I am proud of them, and I

always will be.

My kids know that I accept them for who they are … Flaws

And All … Unconditional.

I was raised on Maryjane and Chicken Soup.

The Bank

Laurie Jordan

Torrey slammed the hatchback down, squashing all of his

earthly possessions that were jammed into the back of the old,

rusty, and badly hail-damaged Pacer. He turned around and gave

a middle finger salute to his now ex-girlfriend, Mary, who was

firmly planted on the porch with a wooden baseball bat gripped

between her hands, ready to swing. He got into the passenger

side of the car, scooted over the console into the driver’s seat, and

turned the ignition. The car groaned, and the engine made a loud

thunk. He turned the key again. The beast hesitated, then started.

He backed out of the apartment complex driveway and sped off

down the alley, then turned onto the street, thinking about his

new situation: he was homeless.

Torrey decided to pay his mom a visit and get some money

before he started making calls to see which friend would let

him crash on their sofa for a few days. He drove to the entrance,

took a left, then a right, and drove on a narrow path, only wide

enough for one car. He parked the car, grabbed his tan burlap

messenger bag from the back seat, and walked across the lush

grass, looking down and scanning the ground from the left to the

right, then stopped. “Hey, Mom. I’m sorry, it’s been a long time.

I can only stay for a minute or two. I need to find a place to live.

Mary threw me out for good this time. I’m not too broken up

about it. Heck, we was only together for three or four months.

Plus, she’s got a crazy kid. His name is Greg. I’ve never met him.

He is going to be coming to live with us. Uh, I guess I mean her

now that I don’t live there. He’s been out on his own for a few

years. I’ve never met the dude, but he sounded like a real piece of

work, a total junkie. He’s a meth head,” he explained. He threw

his jacket down and sat upon it. He patted the cold, black marble

gravestone that was almost flush with the ground and bowed his

head for a second or two. Torrey missed his mom. Even though

they had a rocky relationship and she didn’t approve of his

criminal lifestyle, they loved each other.

Torrey hadn’t been to visit his mom in a while and felt a

tinge of remorse. He didn’t have time for any more chitchat or

“I’m sorries.” He needed to get down to business. He removed a

small, silver garden shovel from the messenger bag. He unzipped

a side pocket and pulled out a wood ruler. He placed the ruler in

the center of the headstone and measured out nine inches away

from the headstone. He grabbed the shovel and carefully sliced

through the grass and earth, as if he were cutting a cake. He

pulled the disk of grass and dirt up and set it aside, so he could

place it back in the same spot. He dug down until he could feel

his shovel hit metal. Torrey felt a sense of relief and muttered,

“Yes!” He dug up a small, metal, circular-shaped can. He brushed

off the dirt and peeled off the plastic lid. He pulled out a roll of

money, smelled it, then removed the rubber band and started

to count the bills. “$5000 big ones,” he said. He took $3000

and placed it into the back pocket of his Levis. He placed the

remaining $2000 back into the can, secured the lid, and tossed it

into the hole. He muttered, “Thanks, Ma. I knew I could always

count on you. See, I didn’t take it all. I left some for another

time.” He patted the top of the gravestone like he was patting a

dog on top of its head.

After Torrey’s mom died, he used her grave as a bank. He

usually earned money by selling stolen things, and if he didn’t

have anything to sell, he donated plasma. He didn’t want to use a

traditional bank, so he used the bank of Mom. He knew that no

one in their right mind would dig around a grave. Keeping the

money with Mom was a smart and safe plan, a plan he shared

with no one.

Torrey looked around to make sure he wasn’t being

watched. The cemetery was in a rough part of town, and you

never knew who was lurking around or setting up camp in

the wooded area. Just over the hill from the crematory was a

methadone clinic, and down the street was a homeless shelter. He

was always cautious when he visited Mom. Torrey never came to

borrow money from Mom during the day, but this time, he was

more than desperate.

He replaced the dirt and disk of grass and patted it down

with this hand. “Looks good,” he said. He stood up, brushed his

hands off on his jeans, picked up the bag, and said, “See ya, Ma.”

He turned to walk back to the car, and then he stopped to take a

leak next to a lilac bush. He heard the sound of crunching leaves

and turned his head to the right and then the left. Standing next

to him was a young man, about six feet tall, with buck teeth, sores

covering his face, and wearing tattered, dirty clothes. He pointed

a handgun at Torrey’s head.

The gunman said, “I seen you, ha, yup, I seen you. I know

you have cash in your pocket, and there is still some in that can

you buried. Gimme the cash, NOW.”

Torrey placed his hands in the air, just like he had done for

the cops a few weeks ago, and he said, “Now wait a minute. You

ain’t gonna get shit out of me, bro. Let’s talk about this.” Torrey

flashed his movie star smile at him, hoping it would help this

dude see that he wasn’t a threat. The young man appeared to be a

meth head. Torrey had seen it before, and this guy was textbook.

He had dark circles under his eyes. His teeth had seen better

days. He was extremely thin and gaunt looking. He had sores on

his face and neck that had been picked at. His hair was greasy

and long. This guy appeared to be a mess and probably needed a

fix. Torrey said, “How about I give you $100.00 and we pretend

this never happened?”

The young man cackled, cocked his head to the side, opened

his eyes wide, and hissed, “You are a dead man, and I’m gonna be

a rich one in about five seconds.” The young man started to count

backwards, “Five, four, three, two….”

Torrey started to back up and decided to make a run for it.

He ran in the opposite direction of his car and headed for the

woods.

The young man screamed, “You’re dead, you’re dead, asshole.

I’m gonna kill you and spend all your money. Now … you is

gonna die.” The young man, with his gun still raised, pointed at

Torrey and fired.

Torrey screamed and cried, “NOOOO.” And he could hear

the gunman laughing. After the bullet lodged into his upper

back, the pain was so intense, he was unable to walk or run away.

He was stunned; he hadn’t thought this guy would actually shoot.

Torrey felt dizzy and started to fall to the ground. On his

way down, he grazed his head on the corner of a black marble

tombstone. Blood was gushing from the bullet wound in his

back and his temple. He tried to get up but couldn’t. He was able

to muster the strength to roll onto his back and look up to the

sky, but he couldn’t see sky; he could only see the young man’s

scabby face inches from his own. He could smell the rank breath

of the junkie. Torrey muttered, “Help me, call an ambulance, call

somebody, or I’m gonna die.”

The young man hissed and spat as he spoke. “I told ya,

asshole, you is gonna die, and your money is mine, ha, ha, ha.

Now shut up, and get dead already.” The young man stepped back

and kicked Torrey in the side several times. Torrey went limp, but

his eyes remained open. The young man didn’t know or care if

he was still alive or dead. He bent down and rolled Torrey onto

his side. The junkie removed the roll of cash from Torrey’s back

pocket and placed it in his own pocket. He also helped himself

to Torrey’s car keys, silver wolf head necklace, and the gold pinky

ring he was wearing. The young man took the burlap satchel and

walked away from Torrey.

He went to the gravestone where he had spotted Torrey.

The young man sat down on the ground and started to dig. It

didn’t take him long to reach the tin can. He placed the can in

the satchel, walked to Torrey’s beat-up Pacer, and tried to open

the door. It was stuck. He opened the passenger side, got in,

scooted across and over the console, fired it up, and drove off.

When the young man pulled into the apartment complex

parking spot, Torrey’s rusty car sputtered to a halt. He spotted his

mom sitting on the corner of the porch; she stood up when she

saw the all too familiar Pacer pull into the parking lot. She had

a baseball bat in her hands. She was yelling, appeared to be very

angry about something, and was waving the bat around like she

was going to hit someone. The young man got out of Torrey’s car

on the passenger side and stood by the car. He cautiously waved,

and yelled, “Yo, Ma. It’s just me, Greg. Geez.” He shrugged his

shoulders and said to her, “What’s up? Whatch ya so worked up

for, and why are ya swinging a ball bat around like some crazy

woman?”

It took her a moment to realize who he was; she hadn’t seen

him in a few years. He didn’t look very good. She stared at him

and looked confused. She put the bat down and hollered at her

son, “Greg … where did you get that car? That’s not your car.

Where is Torrey?”

Greg replied with a shrug, “Who’s Torrey?”

Freak Show Funeral

Nate Detty

It’s peaceful here in my pillowed bed at the front of the tent

where I

am surrounded by formerly familiar faces now estranged by the

places

grief has taken them. Faint shouts drift in from just out the

entrance,

“Gather round! Gather Round! Get your seats to the saddest

send-off in town!”

Mourning wallows in the orange glow from the circus lanterns

burning, casting an eerie

radiance on the bereaved audience that awaits my interment.

Rows of empty chairs echo my isolation.

The chill of death invades the vacancy no longer kept

at bay by the hot breath of a boisterous crowd.

A shush takes the sole seven grievers when a man enters, his

swallow tail coat sways

behind him as he sashays to the front. I can feel his presence

when he stops just

before me. A sorrow so thick as he bows his head it transcends

dimensions

to reach even me. He turns to face the few who have come to

grieve.

He looks past the bearded lady, her whiskers slick from her tears,

to the contortionist,

whose grieving has been predictably kinky, tied in knots around

the illustrated man.

The midget’s flipper appendages are wrapped around the shin of

the world’s tallest

man, his face buried in knee to conceal his weeping.

Tears race down the tracks on the lion tamer’s face, left behind by

the lions

he can no longer tame, which is why he is clinging to that box of

kittens.

The sword swallower is so sorrowful that he wants to eat dull so

he’s sitting alone, eating grapes whole.

There’s nothing else for him to see as it seems angst is the only

thing filling the rest of the space.

The ring master clears his throat demanding attention, his

nervous fingers

twirling the tips of his handlebar mustache, the same way he

always has.

A dozen eyes descend upon him in silent anticipation of his

lamentation.

He bows his head again before his eulogy begins,

“My friends,

We charge five dollars for general admission, a fair price, I’d say,

to let them in.

They flock to our tents when we come to town, they are always

impatient,

eager for entertainment, never hesitant to gasp, laugh, ‘awe,’ stare,

and gawk,

before they return to their normalcy.”

“It is evident, however, in all of these empty seats that your

novelty

wears off once they’ve seen you. It does not matter that your

name is

not The Bearded Lady. They will offer no sympathy for they do

not pay for

your company. They pay for the show, to look at the freaks.”

“We are the only people who will grieve when we leave this

world.

No one ever goes to a Freak Show Funeral.”

Just a Cook

Nate Detty

I am a cook, make no mistake, a cook not a chef.

I’m not the one you’ll see on TV receiving praise for the amazing

meal the critics just ate. I’m just the one who made it.

Mine is the thankless existence of a lifelong line cook.

An industrial kitchen is my church, the grill is my altar

where I sacrifice the flesh of innocent beings

to the almighty printer that screams its demands

in encrypted abbreviations only a few understand.

Its tickets are my scripture that I follow explicitly,

unless of course the prophet that penned it is being a bitch,

in which case that particular chapter gets ‘lost.’

That’s a sin, of course, but I’ll pay my penance by polishing

stainless steel until the cleaner singes my insensitive skin.

Our confession booth is just out the back where we stop

whenever we take out the trash to smoke whatever we

happen to have on hand.

“Mise en place,” is my prep-time prayer.

We worship in ‘revenue’ 5 to 9, seven nights a week.

I can get so caught up in our angry God pushing in orders,

that I’ll start speaking in tongues.

“EIGHTY-SIX PILAF!”

“ORDER-FIRE A PORTER!”

“RUN THE DISH DAMNIT, IT’S DYING ON THE PASS!”

“NAVE’S IN THE WEEDS AGAIN!”

“16 STEAKS ALL DAY!”

“THAT LINGUINE’S S.O.S.”

“CLEARED THE RAIL!”

Mine is a vengeful Deity, a smiting Divinity, and a whorish

Holiness,

but it’s the only thing that can give me that rush that somehow

brings peace.

The Bridge

Nate Detty

Stan walked slowly along the side of the bridge, pulling

his long trench coat tighter around his torso in a futile attempt

to keep out the bitter cold. It was a beautiful night. A crescent

moon hung in the clear, dark blue sky. The only obstruction to

his view of the stars was the faint glow of light pollution which

perpetually fogged the city’s nightscape. The impediment to the

stars made him miss home more than anything else. He closed

his eyes as he walked and pictured the night sky back home.

His thoughts inevitably turned to a quick drive out into the

countryside, to parking on the river bank and lying in the bed of

his old Chevy with Valerie, his high school sweetheart, while The

Killers’ “Midnight Show” played in the cab, and they looked up at

those stars.

He stopped walking and leaned on the railing of the bridge

as he thought about that night and what it had meant. He had

been sixteen. His driver’s license had been still warm from the

printer when he stuffed it into his pocket and jerked the keys

from his father’s hand before he ran out the door to that white

truck. He barely heard his father shout something about twelve

o’clock somewhere behind him. Being the first with the freedom

garnered by the possession of a license, he went out with the

boys first. They did what teenage boys typically do with a 4×4

in rural Nebraska: they tore through muddy fields; they spun

the tires on the gravel roads; they even hit a crossroad with

enough speed to get all four of those tires off the ground. After

dropping his friends off one by one, he drove to Valerie’s and

parked up the street, close enough to see the window of her

basement bedroom but far enough that he wouldn’t be noticed

by her parents. He had thought it would take more effort to

convince her to sneak out and go for a drive, but one text was all

it had taken. He remembered the rush he felt when he saw her

window open while he was still waiting for her reply, the way his

nervous energy encroached upon crippling fear and mingled with

uncontrollable excitement to make his heart race like it never had

before and rarely had since. They drove through the country in

silence, his arm around her, her head on his chest, the windows

down, and the cool summer wind flowing through the cab.

They spent the rest of the night under the stars in the bed of his

truck where they made awkward love for the first time in their

young lives. She cried after, he told her he loved her, and then he

held her as they looked up at the stars until the first rays of the

morning’s light began to taint the night. His dad was waiting

up for him when he got home, and that violation of his father’s

trust had earned him another six months before he was allowed

to drive again. “Worth it” was how he had always finished telling

that story.

Now, eighteen years later, he stood in the middle of a

bridge on the other side of the state, staring out at a freezing,

motionless river flanked on either side by the twinkling lights

of two different cities, desperate to remember how he had felt

that night and wishing he could see the night sky over his home

town just one more time. He placed his hands on the railing

and leaned out to look down at the half-frozen water. He had

reached the middle of the bridge before stopping, just far enough

from either side that the reflections of the light didn’t reach

where he stood. Instead, he gazed down at a smooth sheet of

unforgiving darkness. How cliché this is, he thought as he stood

there, unsure of whether he was attempting to gather the courage

to jump or to walk away. He lost himself as he stood there and

drifted away from reality. Clarity left his thoughts, replaced by an

indistinguishable murmur that drowned out the shuffling noises

of an approaching visitor. He had no way of knowing how long

he had stood there when a sudden, unexpected, deep and harsh

voice spoke up, bringing him back to reality, “You gonna jump?”

He snapped his head to the side to see a homeless man

standing before him. The man had long, graying brown hair that

was dirty and unkempt, with a long scraggly beard to match.

He wore a light green coat that was too big for his frame and

stained in too many places to count. His jeans and shoes, just as

dirty as his coat, were ragged and holey, and his smell of booze,

sweat, smoke, shit, and piss pierced even the dead winter air. In

one hand he carried a fast food cheeseburger with one bite taken

out of it, the greasy paper wrapper folded back to reveal the

greyish meat, and in the other, he carried a cheap plastic bottle of

whiskey. The lid was missing.

“Who the hell are you?” Stan asked, ungrateful for the

company.

“I’m Frank,” he said. “You gonna jump?” Frank asked again.

“That’s the plan,” Stan said before he turned back to the

river.

From the corner of his eye, Stan saw Frank follow his gaze

and look down over the bridge at the cold, murky river and take

an eager bite of cheeseburger.

“What a cliché,” Frank said around his mouthful of halfchewed burger.

“I thought the same thing,” Stan said.

They stood side by side looking out over the water, silent

except for the smacking of Frank’s lips as he hungrily devoured

an obviously infrequent meal.

“Are you going to try to stop me?” Stan asked without

looking up from the river.

“Nah, man. I’m just here for the show,” Frank said.

Stan chuckled and noted the lack of any real effect the

stranger’s contempt had on his resolve. From the corner of his

eye he saw Frank take the last bite of his burger, wipe his mouth

on the back of his hand, crumple up the paper, and toss it over

the side of the bridge. Together, they watched it drift down to the

river. Once the wrapper reached the water, Frank put the whiskey

bottle to his lip, tilted his head back, and took a long pull before

he let out a rasp of breath and shook his head.

“Why, though?” Frank asked.

“Why what?” Stan asked, although he knew what Frank

meant.

“Why you wanna kill yourself, man. Why you gonna jump?”

Stan took a deep breath and kept his gaze fixed on the

river. The two men once again stood in silence, Frank taking the

occasional pull from his bottle, Stan contemplating the answer to

Frank’s question.

“It’s not what you think,” Stan finally said, his eyes not

moving. “I’m not depressed, or sad, or lonely, or any of that shit

people always assume when someone kills themself.”

Frank looked at Stan, then down at the river. “You sure,

man?” he asked.

Stan’s stare never left the water as he once again thought

about the night with Valerie in the bed of his truck. He saw that

night as the last time he had felt hope for his future, the last time

he had felt excited and eager about what life had in store for him,

the last time he had seen tomorrow as a wonder instead of just

another chore to be done.

“I’m sure,” Stan answered. “I was happy once. I’ll spare

you the details, but I lost that. I sank into a depression that

has consumed most of my adult life. It went away. I can’t

even remember when, but I woke up one day, and I wasn’t

sad anymore. Nothing replaced that. I haven’t had a genuine

emotion in years. Nothing makes me sad, nothing brings me joy,

nothing excites me, disappoints me, intrigues me. Nothing. The

realization that I’ve already experienced the best my life has to

offer had no effect on me. Not even the prospect of ending it can

phase me now. But I go out every day and put on this fake smile

and go through my life like the good little boy I am supposed to

be. That facade is freaking exhausting, and I’m tired. I’m just…”

He took a deep breath, slowly let it out, and hung his head.

“Tired.”

“That’s messed up, man,” Frank said.

Frank took another pull from the bottle and held it out for

Stan. Stan took his own long pull, handed it back to Frank, and

the two once again stood in silence staring at the river. After

several minutes, Frank gestured towards the river where he had

thrown his wrapper and then spoke.

“That’s the first thing I’ve eaten in weeks,” he said. “It’ll give

me diarrhea later, and I won’t have it in a bathroom or any toilet.

No, I’ll be doing that squatted down in some alleyway, praying

like hell that I don’t get caught, that no one sees me having

diarrhea all over their alleyway and tries to chase me away with a

broom. You ever try to run away from someone who’s hitting you

with a goddamned broom while you’re having diarrhea? No, you

haven’t. You get it all over yourself.” He paused. “I tell ya, man. I

don’t like smelling like shit.”

Frank reached into his deep coat pocket and pulled out

a lighter and a cheap pack of cigarettes. From the pack, he

produced a cigarette that looked as though it had been rolled in

grocery store bag paper. He lit it up, took a long drag, and let the

smoke out into the night.

“Three of my toes are black,” he continued. “I think it’s

frostbite. The hospitals are required to treat me, and by that, I

mean, I’ll lose my toes. If I’m lucky, I’ll keep my foot. I’ll get

a few hours in a warm bed, probably a meal or two, but as fast

as they can, they’ll throw me back out to freeze off more body

parts.” He paused to take another drag of his cigarette and

went on. “You know that bar, Tarts, I think it’s called, right up

the street from here? No, you probably don’t. That’s not your

scene. Anyways, you don’t even want to know what I did for

thirty bucks out back of Tarts tonight. Thirty bucks, man. That’s

apparently what my dignity costs now, and no one looks me

in the eye. Not even you, man. How messed up is that? Here

you are ready to jump off this bridge, to kill yourself, and still

thinking you’re too good to even look me in the f***ing eyes.”

There was another long silence and the two men stood

shoulder to shoulder as Frank’s words hung in the air. “Are you

gonna jump?” Stan asked Frank, breaking the silence.

Frank looked at Stan, flicked his cigarette out over the

bridge and answered, “Not a chance man. I’m full tonight. The

whiskey keeps me warm. I got smokes. I got like seven bucks

left. I’m fine.” He reached his hand up and patted Stan on the

shoulder. “You’re tired,” he said. “You got it rough, my brother.”

Frank patted Stan’s shoulder one last time and walked

behind him. Before walking away, he placed both hands on the

railing, leaned over it, and looked straight down.

“It’s pretty deep here, man,” he said and pointed towards

the bank. “You may want to head towards the side, aim for the

rocks, you know?”

Stan stood in silence as he watched Frank slowly saunter

down the bridge and out of sight without looking back. It wasn’t

what Frank had said that angered Stan, or the way Frank had all

but dared him to go through with it. It was the way that Frank

had walked away without even looking back that really pissed

Stan off. Who the f*** is this guy, Stan thought, seething over the

thought of Frank daring him to kill himself and then walking

away so nonchalantly, as though his actions had no consequences.

Stan wondered if Frank would feel any remorse if Stan did jump.

Stan imagined the outcome of his jump. He pictured Frank

walking along the bank of the river in the morning light still

carrying the bottle of whiskey, the lid still missing. He saw Frank

look out into the shallow river, and he saw Frank’s unshifting

expression when he noticed Stan’s broken body lying mangled

and lifeless amongst the rocks in the shallow water. He watched

as his imaginary Frank waded into the frigid water, inching

closer to Stan’s body until he could see it bloating and the skin,

much paler in death, puckered from bathing in the cold water.

He imagined Frank kneeling down next to the body as if in

remorse. Then Stan’s imaginary Frank suddenly reached out

and pulled the wallet out of the lifeless Stan’s back pocket. Stan

couldn’t even imagine someone caring about him.

He turned back to the river, unable to think of anything

but Frank. He wondered where Frank had wandered off to,

how Frank would be spending his evening. Again, he was able

to imagine Frank very clearly. This time, though, Stan couldn’t

help but imagine Frank waddling down an alleyway as fast as he

could with his pants around his ankles, losing his bowels behind

him as he fled from an old woman in a black, ankle length dress,

her long gray hair tied up in a bun and swinging a broom at the

defecating runner as she screamed, “You get out of here, you

filthy man!”

It started as a single chuckle. The involuntary lurch in his

ribs and chest seemed almost foreign to him. Then came another

slightly larger lurch, and a gleeful sound escaped his lips. Slowly,

he started to recognize the undeniable signs of a serious case

of the giggles. He tried to stop them, but again saw the absurd

scene of Frank trying to pull his tattered pants up as he ran away

from the angry old woman, and he lost it. The giggles grew into

raucous, guffawing laughter, and soon Stan was doubled over

in the middle of the bridge, holding his ribs with one hand and

the railing of the bridge with the other, laughing uncontrollably.

He laughed loudly and violently, like a man who had finally lost

his fledgling grip on reality. He laughed until it hurt, until his

throat was raw, and the guffaws turned into coughs and desperate

gasps for air. He laughed until the heaving and lurches made

his ribs ache. He laughed until his aching ribs, raw throat, and

coughing brought tears to his eyes, and then he cried. He gave in

immediately when the tears started. He dropped to his knees and

wept in great heaving sobs.

The Eight Stages of Loss

Amanda McLeay

ONE

Foot in the door and I

know something’s wrong, it

shouldn’t smell like bleach.

TWO

There is no sound but silence. No

whirr of the saw. No

buzz of the drill. No

sound of their ever-running mouths.

THREE

Boss Man left, the treasure

packed in a cooler

on the front seat. The missing

piece hidden

in the lumber.

FOUR

Power is knocked

out of the shop as if gale forces

blew through, leaving only clouds

of sawdust.

FIVE

His tools sit quiet. His wife, hammered

face like steel. He’s okay,

he’s shaken, he’s repeating,

“It happened so fast.”

SIX

Ghostly echoes are glued

to all thoughts:

the smack

of the board, the yell,

the panic.

SEVEN

The sharp blade

changed his calloused

hands. Their final fate

drilled by the doctor’s

words.

EIGHT

I clench my fists, nails

punctured into my palms.

I count my small fingers

one to ten as he counts

one to eight.

How My Jazz Turned into The Blues: Sonny’s Side of the Story

Douglas Anderson

Based on and inspired by the short story “Sonny’s Blues”

by James Baldwin

Rat ta tat tat … Rat ta tat tat … The sound of that sweet

steady beat kept us up jammin’ all night. Man these cats can lay

it down, I mean really lay it down. Time just floated along. You

know how it is, once you’re in the groove.

If we can keep it all together for a few more weeks, you

dig, we might be up there at The Five Spot where guys like Bird

and Monk play. We almost got all our own equipment, so we can

keep that extra scratch they charge to use theirs at the club.

Last week, Fathead, you know that cat that blows for Ray,

come through and jammed with us. I tell ya, we was smokin’! I

told him that next time he’s in The Apple, slide on through the

Village, and don’t forget that brown sugar!

Rat ta tat tat … Rat ta tat tat … BOOM!

The door rips open, and there they are. Cold blue steel

and copper badges standing firmly over me shouting words like

“premises” and “evidence” that I can barely comprehend in this

drugged state.

“Hey man, what gives?” I tell the rigid men in their starched

blue uniforms, “I was tryin’ to get a little sleep!”

(The truth is, horsey is still runnin’ a little wild, so I ain’t

quite with it, dig?)

“You’re under arrest, Sonny. For peddlin’….”

“Hey, I ain’t got no bicycle, Jack.”

“For selling dope, funny man. You know, heroin, smack, or

whatever you junkies are callin’ it now.”

I decide through my hazy thoughts that I might just be

trippin’. Yeah, trippin’!

“Is this some kind of a joke, man?”

The man’s pointed kneecap in my back and the shiny

chrome-plated bracelets he is so lovingly clamping on my wrists

are sure signs that it is not. The baton across the back of my head

cracks like lightning through the clouds from the heroin.

The tornado that ensues inside the apartment does little

to help the DA’s case against me, but it completely destroys

everything that I hold dear. They rip the top cover from the piano

and the bench, cut holes in the drums, tear apart the cases for the

brass, and smash the guitar.

Even the records are suspected of hiding drugs that they are

so certain they will find. No one will be playing them again. The

apartment floor is littered with torn up record sleeves and broken

vinyl. My precious wax.

I’m sure this is out of spite. They’re just mad cause they can’t

find no dope here. I’d heard they been watchin’ the crib cause

there are a lot of cats that hang around the place, mostly just

jammin’! But ya know, rent ain’t free, and that bitch ain’t either, so

yeah, I gotta flip a little.

I ain’t saying I’m a pusher, but I ain’t no angel either. I just

do what I gotta do to make the rent, dig? Besides, I like to stay

high. It makes me feel bright in this dark world. When I’m ridin’

that horse and my fingers caress those sweet smooth keys, I feel

the whole shit of the world just melt away in the sun.

The booking area is full up. It’s always full up. Drunks

hollerin’ at the cops, hookers hollerin’ at the drunks, and the

cops hollerin’ at everybody, it’s crazy! This ain’t no place for a cat

like me, and once I’m out in GP, I’m gonna be surrounded by

dangerous criminals!

We’re all cuffed to this long wooden bench in the hallway

waitin’ to use the phone. I got no one to call, I am hit. I feel worn

and dull like the grey paint on the concrete floor. I look up like

there may be some hidden exit, but there is nothing but the

water-stained, sagging ceiling and the fluorescent lamps. Every

corner is lit up, but the place is still full of darkness. It soaks in

slow and steady like drops from a leaking faucet.

I watch everyone ahead of me take their turn at the phone.

You can tell right away the ones that’ll make bail. They exhale

deeply and their shoulders start to relax the moment they hear

the words, “I’m comin’ to get you out.”

I suppose I could call my brother, but I haven’t talked to

him in over a year. He’d just scold me like a child who just spilled

Kool-Aid on the carpet. I think I’d rather stay in here than listen

to one of his, “Hey, come on Sonny, what’s wrong with you,

man?” lectures. He always talks to me like I’m a kid. It’s always

the same—he’s the man who doesn’t hear a word I say, and I’m

the kid brother who is supposed to just shut up and listen. It’s

finally my turn to use the phone.

Rat ta tat tat … Rat ta tat tat … I take a pass.

My name is called, and I approach the judge for

arraignment. I try to explain to him that my ignorance is the

reason I’m here, but he is an alabaster pillar. The DA, with his

files and clipboards held firmly to his heart, slinks quietly to the

judge. He reminds him that I have violated my parole and that

I’m an evil man, guilty of evil deeds—a pusher of heroin and a

threat to public safety. The whole deal is jive. He judges me by

my tattered appearance and my eyes that are red like the devil.

Bail denied.

I know that when I get outta here I’ll have nothin’, and it

won’t be any time soon. The rent’s already a week late, and the

landlord sure ain’t cuttin’ me no slack again this month, not after

he sees the place. The wreckage of my life is broken and scattered

all over the floor. Even the few things spared from the fury of the

raid will be tossed in a dumpster.

Rat ta tat tat … Rat ta tat tat … my stuff ’s in the trash.

The eight by eight cell at Riker’s is cold and sharp. It reeks

of body odor, feces, and despair. On the toilet/sink combo in

the back is a short, fat, dark-skinned man in his forties. He’s

bald on top, and the little hair that remains is greased down and

wavy. He hollers out to me, “Soon as I’m done takin’ a sit, we’ll

talk about how things go ‘round here.” He smiles with a gaping

wide grin and slaps his knee. “Just to clear the air!” He has a loud

heckling sort of laugh.

Things were looking bad before. Shoot, I’m in jail, ain’t got

no scratch, the withdrawals from the smack is kicking in with full

force, and now I got a crazy cellmate named Tubs who likes to

make jokes while he fills the air with nerve gas.

Days blur into months, and each one rasps away a little

more of me. Even when it’s sunny outside I feel dark and lonely,

but Saturdays are the worst. That’s when you can have family or

friends come to visit. In nine months nobody’s been up here to

see me. I haven’t gotten a single piece of mail.

Every night I wonder if my brother knows where I’m at,

or if he even cares. He probably does know, but doesn’t want his

brother, who is a convicted felon and a heroin junkie, screwing

things up for him and his family. It feels like having all of my

bones broken knowing that no one misses me. I am loved by no

one. Maybe I belong to this darkness.

Sometimes I think about sending my brother a letter, not

to ask for money or anything like that, but just to see how Isabel,

him, and the kids are doin’. Being locked up in here got me off

the dope and has given me time to clear my head. I miss all of

them so much, I regret all of the time that is lost.

Rat ta tat tat … Rat ta tat tat … can’t get it back.

That steady beat kept me up all night.

We been waiting in the lunch line for years it seems like.

I’ve been silent, making sure not to make any eye contact. Tubs

is wearin’ that big silly grin he gets when he can’t wait to tell ya

somethin’.

“See, I’m a Blues man,” he tells me as he rocks back and

forth, heel to toes, with both hands hanging out of his pockets

by the thumbs, “and ain’t no place will give ya the blues like this

place here.” I agree.

“Blues?” I tell him, “You can’t dance to The Blues! How you

gonna dance to The Blues?”

Rat ta tat tat … Rat ta tat tat … Can’t dance ‘cause you fat!

“Man,” I tell him, with my hand patting him on the

shoulder, “jazz is my bag. Baby, it’s the cat’s meow! You dig?”

“All you guys tryin’ to be like Duke or Diz these days,” he

chuckles a little. “Yeah, you young pups like that whole scene, but

it’s got no soul to it.”

“Jazz is about being alive, dig? It don’t need no soul, souls

are for when you dead!”

“The Blues is about livin’.” This time it is him who puts his

condescending hand on my shoulder, “Now look here son, what

was you doin’ before you got here? Besides playing the keys.”

“You know what I was doin’!” He sounds like my brother

warming up for one of his speeches.

“You wasn’t livin’,” he says patting my shoulder, looking me

straight in the eye without blinking. “What you was doin’ was

hiding from life.”

“Wait a minute, man. You sound like my brother now,” I say

jerking back to free my shoulder from the oppression of his hand.

“Don’t you for a minute think that you can judge me! We do

share a cell in prison, remember?”

“I ain’t judgin’ you, I’m just sayin’ I understand what it’s like.

Man, I would get so high on that Junk and beat them skins until

they took me clean off the Earth. Then one night I was playin’

with my Uncle Creole and them. After we jammed he took me

aside and told me that I wasn’t feeling my music, the only feeling

I had was high.”

“See, it ain’t that I need to be high….”

“You’re missing the point. When you let go of all the

darkness, and let your music flow straight out from your soul, it

will free you from the shackles of pain suffered in your life. That,

my friend, is The Blues.”

Me and Tubs finish up our lunch and head back to the cell

where most days I like to read because it takes me away from this

place for a little bit. Tubs always sits for a while and then takes a

nap. For the last few days I’ve been reading Notes of a Native Son

by a guy named James Baldwin. He grew up in Harlem not too

far from where we did. It’s cool, but I’ve got something else to

read.

Today I finally got a letter. The return address says it’s from

my brother. I am flooded with happiness. My vision gets blurry,

and I struggle to hold back tears. It’s been close to two years

since I’ve heard from him.

I open the letter, and my eyes immediately zero in on the

words, “Gracie is dead.” My hands begin to tremble. Gracie is

dead. I read them over and over. They might as well be the only

thing written on the page. The joyous tears I had been holding

back are washed away by hard tears of sorrow.

Out of the darkness, from somewhere far away, I hear Tubs,

“Hey man, you okay?”

“Gracie is dead,” is all that I can say. It is tar that sticks to

my mind all day. I don’t bother with dinner or anything else.

The lights are about to go out, and I lay here thinking about

what Tubs had told me earlier, my life, the letter that I got from

my brother, Gracie, Ma and Pops, and all the hard times we have

lived through. I close my eyes and start humming a tune I’ve

never heard before. It’s slow, soothing, and seems to embrace

pain. I don’t have to think about it, it just flows out free and pure,

like spring water.

Number Nine

Terry Grigsby

Heaven sports an All-Star Team

Full of sharp lifeless folks.

Cure to Cancer in the grassy knolls.

Inventor of the famous iPhone.

Heaven gleams with amazing people.

Why is death even a real thing?

Thirty-eight presidents talkin’ politics.

Wilt Chamberlin shootin’ hoops.

Heaven is really number nine

A planet of its own, glowing sky high.

Mothers and fathers smiling down.

Henry Ford out for a cruise on the town.

Why can’t we just all stay together?

All of those monumental corpses.

Heaven will forever be paradise.

Living with all those All-Stars must be nice.

Ode to Cucharitas

by Carissa Caudillo

The big vibrant green, yellow, and blue striped bowl sat sturdily against the white wall between the coffee machine and the dark green stove top. It was filled with what looked like, from a distance, small white plastic spoons. But as I made my way closer–curiosity inching me towards this counter top—I got up onto my tip toes just barely seeing closer into this foreign bowl on my kitchen counter. I saw bits of rusted orange color upon these plastic spoons. I reached out my stubby nine-year-old arm as far as it would stretch when the sound of my dad’s voice made my heart jump right out of my chest.

“Do you want me to get you one, mija?” my dad teased knowing I was too short to reach.

“Yes, please,” I answered. He chuckled and reached his large hands, scarred and calloused because of years and years of working on cars and teenage fighting, into the bowl and pulled two of these irregular spoons out—one for him and one for me. The spoon had plastic over the round end sealed with a red rubber band. Beneath the plastic was the rusty orange taffy that had caught my eyes to begin with. My dad unwrapped the plastic from the end and stuck the spoon in his mouth as if it were a sucker. Confused, I asked him, “What is it?”

He chuckled once more and explained, “It’s candy. The sweet and spicy kind. It’s like pelon but thicker and on a spoon.” Pelon is a candy that comes in a push bottle. You push on the bottom and an orange goo pushes through the top in strands. It’s tamarind and chili powder flavored. “They’re called cucharitas,” he said. “Cucharitas” translates roughly into “little spoons.” But it wasn’t the spoon that was so intriguing, it was what the spoon held.

I unwrapped the candy and I put it in my mouth. It tasted tangy and spicy like a spicy, dried orange. It was rough against the top of my mouth, and slowly dissolved at the touch of my tongue. It tasted oddly like pelon, but grittier. It wasn’t sticky and gooey like pelon but instead it was chewy, and it melted down in my mouth. It was spicy, but not very. It was as if it were tangy, and then every once in a while the chili powder would crawl on one of my taste buds and hold tight. It was just the right amount of spicy. As I got older, I would normally have a cucharita at least once every day after school for a snack. It was as if I had forgotten something if I hadn’t had one all day long.

My dad would buy them from La Guerra on 24th Street, a little grocery store on the corner. They are about 5 dollars for a small bag of sixteen. There are tons of different brands of them, but La Guerra only offered one—the yellow and orange bag. My dad always got that kind from La Guerra because it was the closest store to our house that sold them.

I would eat one when I got home from school after having a bad day. When I was younger, I didn’t have many friends. I stuck to myself and I have always been that way. When I was younger it wasn’t easy to just be by yourself in class because if you sat alone you were a loser. But on days that were worse than others, I always looked forward to cucharitas. Some kids find comfort in the hot cocoa their moms make, but I found it in the cucharitas my dad bought. In a Mexican household there is always a bowl of candy somewhere. You just have to find it. The bowl of candy is like our cup of hot cocoa. No matter how bad my day was I always knew we would have cucharitas in that striped bowl on my kitchen counter. Whenever I was down about something and my dad could tell, he would offer me a cucharita. He knew the warmth these candies would bring me. It was weird how something as simple as candy could change my entire mood. I could be crying like a busted fire hydrant and the sight of this candy would fix my leaking eyes. They warmed my heart.

As years went by, I grew older and that only meant that there were many more bad days to come. Through the years, I can’t remember a time where we didn’t have a bowl of cucharitas. Eventually, I moved out of my dad’s house. I had to move in with my mom because my dad couldn’t afford to take care of both me and my brother anymore. My mom was never really a part of my brother’s and my life after my dad and her split up. All I could remember was that one day, out of the blue, she was in my living room arguing with my dad. A week later I moved in with her.

The first few weeks my dad would bring me a package of cucharitas every week. He would always say, “In case you start to feel down or you want something sweet,” then he would hand me the bag. Eventually he stopped bringing me them, and I stopped going over to his house as often. But every time I would go over there, I would grab one or two. I could always look forward to them. Having these candies in this unfamiliar house and these unfamiliar people I had a sense of comfort—a sense of home.

As years went by I met my boyfriend, Jesus. He would go over to my dad’s house with me, and we would sit there and talk with my dad and eat cucharitas. Soon we began to buy them together. Anytime I would feel bad he would offer me one or he would buy me some of this simple candy that could change my entire mood—and like my dad, he knew they could. Something as simple as candy can remind me of all the good things in life and bring me comfort. We always had a bowl of cucharitas on the kitchen counter.